Zwerge, Gnomes, and Kobolds

Modern mythology has long been clouded by confusion that accumulated over many centuries and concerns the mixing of three peoples that are completely different in energy, functions, and origin, yet similar in the impression they make on people: dark alvs (or dvergar), the elementals of earth (gnomes), and Faerie masters (kobolds and koblins).

Medieval scribes, Renaissance alchemists, nineteenth-century romantics, and translators who did not distinguish the subtleties of terminology all contributed to this confusion. However, if we carefully separate the traditions and return to primary sources, the boundaries turn out to be clear and distinct: each of the three peoples has its own specific features of function, energy, and mind.

The first people are the dark alvs. According to the Northern tradition, it is precisely they who embody primordial form-giving wisdom and the art of drawing an ordered structure out of primal matter. This is an ancient, strong, and wise divine people, kin to the Light alvs; their role is to forge structures and to establish and maintain Matter’s stability. Their homeland is Svartalfheim, one of the special worlds of Yggdrasil, which arose when the light of consciousness separated from the gloomy regions of Niflheim that set out upon the path of formation and manifested being.

However, the dark alvs also spread into other worlds and into the spaces of the Interworld. It is by their efforts that the craftsmanship of the Elemental Cities is maintained and, more broadly, the entire framework of the Faerie civilization of the Interval: in the workshops of Falias, Gorias, Finias, and Murias, it is the svartalvs who carry out the work of forming and securing the elemental supports of the world order.

In the First Age (Kesair) they manifest as bearers of Potentiality — masters of logos, able to translate them into eidos and further into forms; they build the first supports of stability and create the cores of future structures; in the Second (Partolon) and Third (Nemed) Ages they create their workshop clusters in the Cities; after the exodus of the Castles into the Interval, it is they who turn Falias, Gorias, Finias, and Murias from abstract “contracted realities” into active supporting nodes of crafts. In the Fifth Age (Tuatha de Danann) the svartalvs become architects of conjunctions: they link the sidhe Castles with the Towers, tune bridges between the Interworld and Midgard. In the Sixth Age (of Humans) there occurs a catastrophic degeneration of their homeland, Svartalfheim: a technocratic race of igvs develops, while the svartalvs who remain devoted to the old traditions go into the depths of the Interworld; however, they do not disappear, building their workshops into islands of stability of the Interval.

At the same time, Dark alvs come in two kinds: chthonic, subterranean, working with still-chaotic material substrates, and “cosmicizing,” “above-ground,” who create more complex and “technical” objects.

The “svartalvs” proper in the sagas often appear under the name dvergar: the underground smiths forging the bonds of Gleipnir or Loki’s ransom — they are the same smith-aristocracy of the underground Order, where craft is a continuation of logos. The products of the dvergar are hardly distinguishable from magical artifacts: they include Runes and spells, and are still inseparable from spirit.

However, the “above-ground” races of svartalvs are not “dwarfs.” They are masters of complex forms, creating composite material objects from “raw material” supplied from the depths. Their products are more mechanical objects that operate independently or on “coarse” kinds of energy. The most famous representative of this race is Vǫlundr: not a “dwarf-smith,” but a heroic svartalv, a prince and master of the alvs; his craft is so great that he ascends into the sky on the wings he created.

Yet these “tall” svartalvs are always students of the dvergar: they continue and develop what was created in the chthonic depths. And Vǫlundr is also only a “student,” though he surpassed his subterranean teachers in “technical” skill, he still yields to them in deep wisdom.

In general, the Svartalvs people include three interrelated schools:

1) Masters of vaults (hvel-setjar) — Builders, “higher engineers” and “mathematicians,” who calculate the “sky of things”: verify form and curvature, seek natural supports for sites, combine mass and vibrational forces; their work is bridges, vaults, and domes; for them, statutes, oaths, and agreements are important as “vaults” of meanings.

2) Connectors (bind-smiðir) — Smiths, who know the craft of seams, soldering, rivets, hinges, and other types of connections. They are responsible for ensuring that heterogeneous parts do not break at the points of connection, and that the new integrates with the old safely.

3) Rune-binders (rún-bindarar) — Sages, who choose a fitting name for a form. For them, Runes are vectors of constructions, signs of the self-knowledge of forms in interactions and under the load of time.

Svartalvs are not only glorious masters but also famous mentors. They are not simply “teachers of the sidhe,” but elders in craft, from whom the Tuatha adopted the main features of their work: first form — then power (Falias), first goal — then action (Gorias), first boundary — then scope (Finias); first measure — then giving (Murias), how much one can give the world so that it neither bursts nor becomes impoverished.

Therefore in the battles at Mag Tuired the Dark alvs, although they did not fight in the front ranks with spears, their work is evident in the fact that chaos did not collapse into chaos; it was by their efforts that objectives, front, rear, and supplies were maintained.

The work of the svartalvs can be recognized by its strength and durability: their bridges age well, their fortresses weave wind and water into their constructions, their devices do not “defeat nature,” but cooperate with it, and therefore function longer.

Svartalvs also respect their students. They know that for the faerie, “cold iron” is hostile, cutting not only flesh but also magical energies; therefore, they almost never use iron in Faerie artifacts, preferring orichalcum, the sacred metal of the Magical people. For other purposes, they widely use star iron (meteorites, “living,” transformed-by-Magic metal), lunar silver (for flexible nodes), dawn bronze (for supports where the energy of Venus is important). If they do take earthly iron, they first treat it: alloy it, add micro-impurities, cover it with a coating of bronze or gold so that it serves the structure and does not harm allies.

They observe principles of honor: they do not introduce into the world a force that does not “weave” harmoniously into already existing flows.

A completely different nature belongs to the elementals of earth — gnomes. These are natural spirits of the Earth, “earth-walkers,” who pass through stones, rocks, and layers, create and guard ores and crystals; their connection is with the very element — they are the reason of the element.

Paracelsus describes them as a kind of sublunar beings without an immortal soul — and this indicates a different origin and a different energy than that of the faerie and alvs.

In the cosmogonic sense, gnomes act already in the First Age of Earth: when the world is only settling, cooling, and crystallizing, they build its crystal lattices — from reefs and limestone plateaus to the first ore veins.

They precede peoples of craft and state structures: gnomes do not build civilizations; they only form masses of stone and rock, lay down layers, grow crystals, and give weight to any form. They are the force of mass and the energy of stability. Their manifestations are inertia, compaction, nourishment, and embodiment; their cardinal direction is the North; their season is winter.

Gnomes “think with the planet’s body: their wisdom is in the force of gravity, in layers and deposits. Where a gnome passes, a vein comes alive, a crack tightens, a scree stops.

They change their size as needed, bear any loads, guard ores and crystals for maturation; their laws are the generosity of measure, therefore they do not tolerate greed, though they do not allow senseless “squandering” either.

Their natural antagonists are the Dragons of the depths, the fiery forces of the Earth’s deep places, whose pressure and heat liquefy and explode magmas, disrupting the hardening so desired for gnomes; hence the mythological memory of the “eternal confrontation” between Earth and Fire.

Their “cities” are caves, hollow mountains, ore bodies, natural hills and mountain massifs; their “palaces” and “chambers” in legends are only metaphors for the organization and beauty of rock.

They have no rules of war and no ethics of treaties — their morality is geological: to mature, to hold, to weigh down, to feed.

Therefore their descriptions are often contradictory: they act as good-natured guardians where measure and gratitude are observed; and as harsh avengers where a vein is plundered and slopes are destroyed.

With the faerie, gnomes are neither subordinate to nor enemies of: these are parallel kingdoms — the faerie work with forms and rhythms of life, while gnomes work with mass and density.

With the dark alvs, gnomes are close in role (forming structural strength and supports), but not in nature: alvs organize form, while gnomes give it weight; where alvs build vaults, gnomes sustain firmness.

With kobolds, gnomes are neighbors in mines, but they divide functions: kobolds regulate the mechanics of the place — seams, tools, order — while gnomes support the rock’s bulk.

In the system of the Elemental Cities, earth as the primary element is concentrated in Falias, the city of form and truth; however, gnomes are not “citizens” of Falias, but its very structure: they sustain and feed the basal force and preserve the truth of measures, thanks to which form does not empty out.

Their gift is stability: they translate designs from potential into reality, and for this they stabilize and compact them until self-supporting.

Their shadow manifestation is stagnation: that same inertia, having accumulated beyond measure, gives rise to indifference, insensibility, melancholy, a “stone heart.” Therefore, earthly energies require a counterbalance of Air: lightness and “windows” of change.

Gnomes do not demand sacrifices and do not like noisy rites: they are closer to proper routine — honest masonry, patience in drying mortar, respect for construction terms, returning what was taken.

That is precisely why mixing gnomes with dvergar is incorrect: dvergar are bearers of traditions and masters of high forges, while gnomes are an element and guardians of layers.

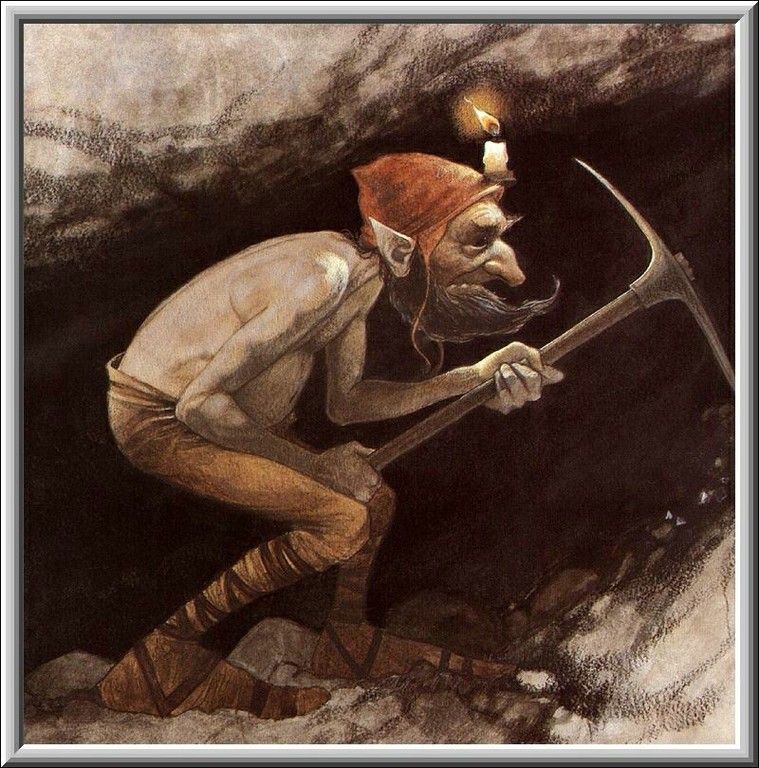

Finally, underground Faerie masters — kobolds and koblins. In German folklore they are described as “mine” dwellers, capricious but more often helpful, capable of rescuing a miner from a collapse or hiding tools if people are rude. These are specialized groups of Faerie masters, keepers of craft secrets, for whom “craft is like prayer.” They study in Falias and adjacent settlements of the Interworld, mend, tune, put in order.

Kobolds are part of the Magical people, long associated with the element of earth and with gnomes; their natural environment is rock, adits, caves, and mines, where they act as guardians and protectors of underground riches and as intermediaries between the element and human ore-miners.

Their gift is to sense the slightest movement of a layer, to anticipate collapses, and when necessary to protect a vein from predatory extraction: to mislead a lost miner with an illusory tunnel turn, to strengthen the wall of a cave by changing the “pattern” of the crystal lattice, or, on the contrary, to open it where order is violated.

In Falias, kobolds have almost merged with gnomes in a working alliance: together they support the fertility and stability of the Earth; but in worlds where people are driven by greed, it is precisely their influence and their Magic that stand behind “sudden” collapses, mudflows, and other “earthly” punishments.

Koblins are yet another “earth” people of the faerie. They are often confused with kobolds, dvergar, gnomes, and nockers, but the legends emphasize: they do not control the Earth’s structure and do not “hoard” riches. Koblins are the ‘nerves’ of the depths, echo-signals of rock, the responses of the underground world to sound, fear, or human intentions. They are small in stature, sinewy and mobile, as if sewn from the memory of generations of miners. They seem melded with stone, coming and vanishing where a human intrudes into the silence of the depths: they will lead the respectful safely through; the cowardly and greedy they will mislead — and the path will turn into an abyss both literally and symbolically. A whisper of gratitude, a piece of bread, a sip of ale — this is sufficient “payment” for them; while disregard for natural laws is the cause of misfortune.

Thus, if svartalvs are the ancient “smith-aristocracy” of form, gnomes are the elemental guardians of layers, kobolds are master-intermediaries and keepers of order, then koblins are the “conscience of the mine,” echoes of the depths, testing human intentions.

Kobolds and koblins are Faerie masters and engineers, the closest to humans in their mode of action; and later human names are also connected with these same peoples — up to the metal cobalt.

Therefore, kobolds can be “translators” between gnomes and humans (they understand both the language of the vein and the speech of the miner), but at the same time they remain faerie — a non-local entity with free will, a distinctive ethic, and their own craft. And where a gnome will guard a layer as a given, a kobold will guard the order of extraction and the justice of exchange.

Dark alvs work with form as a product of logos: they build a vault and sustain the complex construction of the world; their forges are a continuation of the City and Order. Gnomes “bring rock to life” from within: where they pass, veins come alive and crystals grow; they are laconic and leave their trace in geology rather than in chronicle. Kobolds are the hand of Faerie culture: master-engineers, “technicians” of the Interworld; they see work as a Covenant — they repair the subtle mechanics of places and watch over the tooling.

In general, the distinction among the three “earth” peoples can be described as follows: svartalvs/dvergar are bearers of form-giving craft and oath-bound technologies; gnomes are the Earth itself at work, without artifacts and guilds; kobolds/koblins are beings who maintain order in the depths, intermediaries between the layer and the human.

Accordingly, it is necessary to adhere to three modes of interaction, three ethics: for the svartalvs — honor and honesty, for gnomes — the balance of taking and returning, for Faerie masters — moderation, silence, and work discipline.

With such a proper attunement, the Cities will provide supports, the Elements will sustain the harmony of the depths, and Craft will unite them in action — and in each legend it will be clear whose deeds are being described and what consequences they have.

Leave a Reply