Letters and the Logoi

It is clear that the main function of language is the transmission of information which, in its deepest sense, strives to reflect meaning, i.e., the “logostic” component of the universe. The formation, development, and “logization” of language — both spoken and written — happens gradually: it “grows” into meanings ever more deeply and fully as it matures, “comes of age.”

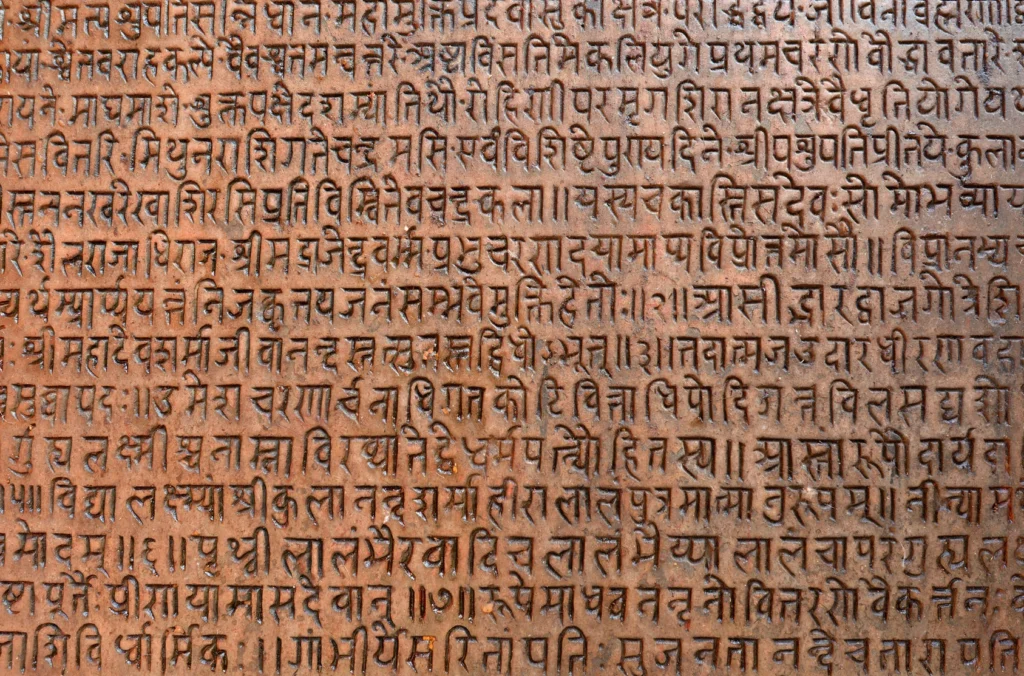

At the same time, each language reflects, of course, both the particularities of the worldview of its people and the ways characteristic of that people for accessing meanings, of “contact” with the hierarchies of logoi.

The fuller the “contact,” the more precisely a word reflects the logos whose manifestations it indicates, the greater the energetic capacity of that word; and a word that expresses a logos in its fullness becomes a Realizational Name.

The same pattern is characteristic of writing: the letters of a developed language also become bearers of energies, manifestations of logoi, forming the vortices or vectors that support these logoi.

Accordingly, the alphabets of such languages reflect not only the elements of meaning accessible to a given people, sound or other means of transmitting information, but also the “elementary logoi” accessible to perception; therefore, the alphabet as a whole expresses the “semantic universe” of that people. It is clear that if the contact between a language and a system of logoi is well established, then such a “universe of meanings” acquires a special power; therefore, among many peoples, writing the entire alphabet was considered a powerful magical act.

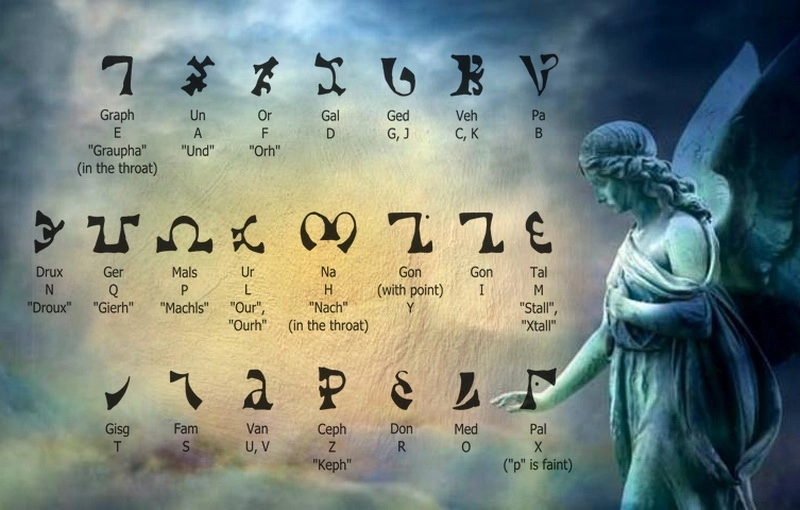

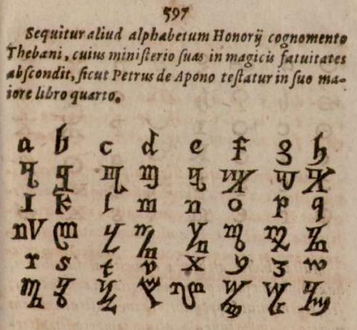

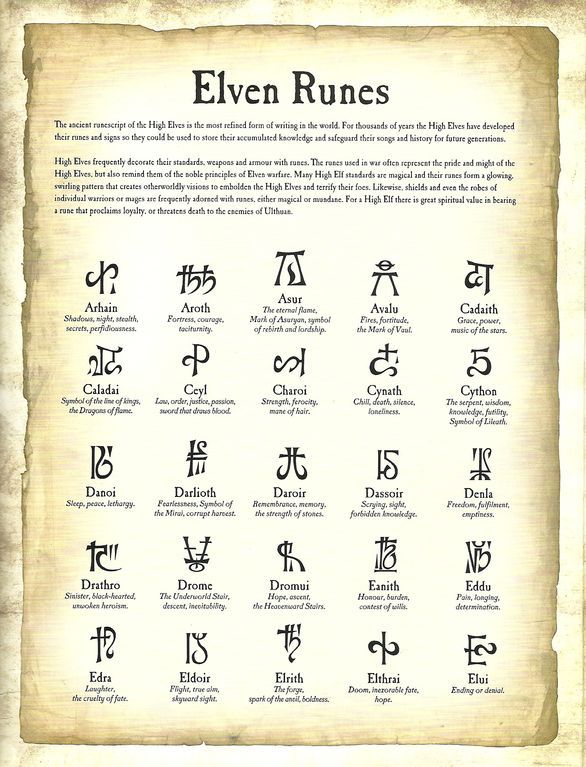

Conversely, throughout history Magi often sought to create their own “semantic universes,” and invented their own languages and writing systems. Of course, an important driver in creating such systems was also the desire for secrecy, encryption, and “arcanization” of their knowledge; however, the realizational aspect also played a role. Some of such “artificial” systems did indeed demonstrate considerable realizational effectiveness and were widely used.

Such systems include the Celtic Coelbren, and the medieval magical alphabets — the “Theban,” “Celestial,” “Angelic,” mentioned by H. C. Agrippa — and Dr. Dee’s attempt to record the “Fomorian” (or, according to the author’s claim, “Angelic”) language in “Enochian” letters, and the famous “Lingua ignota,” and many others. Those interested would benefit from reading the book by the modern occultist N. Pennick, “Magical Alphabets.”

In exactly the same way as the Ritual system of a given school takes shape, as through use it accumulates Experience and Authority, gains momentum and realizational potential, so too does the encoding system develop, increasingly approaching the features and regularities characteristic of a “real” language.

At the same time, the need to create and develop such systems often arises naturally; it is rooted in the inability of everyday sign systems to provide contact with those logoi, vortices, or vectors that a magus, alchemist, or bard employs in their practice.

And in exactly the same way as “natural” languages have had varying success in aligning words, sounds, and letters with logostic hierarchies, artificial systems manage this with varying success.

It is useful for a practicing magus to study both traditional sacred symbolic systems and the available “new-made” ones, and perhaps also to create one’s own encoding system, in order to find a way to contact logoi that suits them and to find Names and Words of Power.

Leave a Reply