Wrathful Spirits

We have already discussed that the pagan worldview takes a broader view of darkness and theodicy.

From this point of view, true evil is the consumption of one being’s resources by another, leading to an impairment of the development of the victim’s mind.

At the same time, there are many other cases that are subjectively seen as negative, yet are not evil. Destructive acts that create space for new development and various forms of active defense can be quite traumatic, and yet entirely necessary.

Such actions can be performed by both “ministering“ and “Free” beings.

There are many accounts of angels who are destroyers. In fact, in the Old Testament, the main role of angels is often to kill or destroy.

However, the case of angels is simple — they maintain the world’s equilibrium “automatically”; they arise as a binary counterbalance to the consuming Power of the Qliphoth.

Things are much more complicated with Free spirits, especially gods.

We have already said that many gods of various pantheons have, as it were, two sides — two faces: the so-called Benevolent and Wrathful faces, which reflect the two aspects of any Power — creative and destructive. Indeed, any Power can bring both benefit and destruction: fire can warm, but it can also burn; water can quench, but it can also flood, and so on.

This concept is most fully developed in Eastern religions. In India, many worship Shiva’s destructive aspects — not only in the relatively neutral form of Nataraja, but also in more terrifying aspects of Bhairava. Even the creator-god Vishnu appeared in a fearsome form, for example, Narasimha.

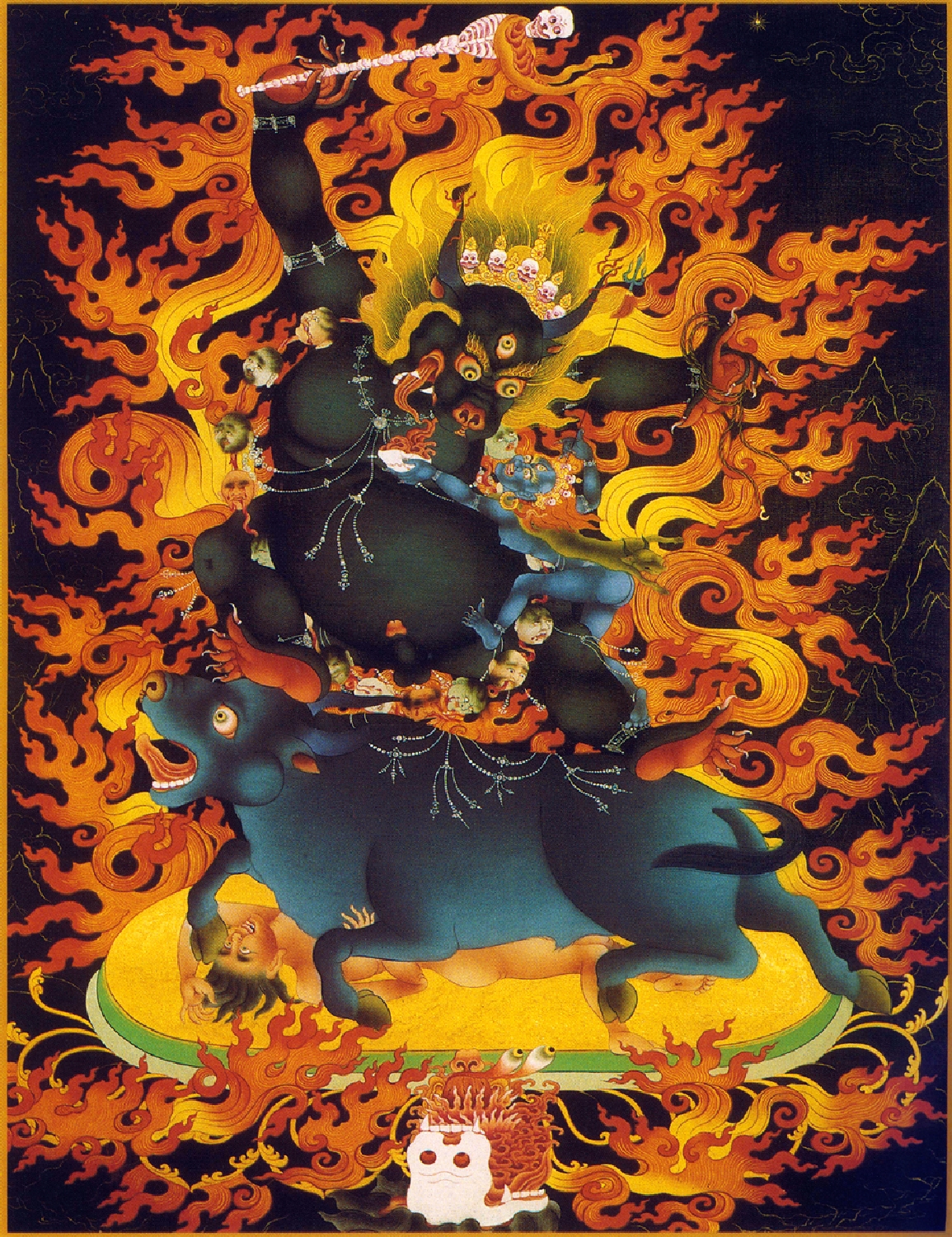

Many such images also appear in Mahayana Buddhism, influenced by Bon traditions: Yamantaka, Mahakala, and other dharmapalas are striking manifestations of such destructive forces.

Western mythology is also rich in images of wrathful gods. Apollo is terrible in his wrath, Odin is dreadful, and Hors is furious.

The serpentine face of Veles and the powerful image of Cernunnos express the corresponding divine Power’s role in actively overcoming obstacles.

The wrath of gods should not be understood as mere anger or as aggression. Wrath is a necessary means to destroy obstacles in a Power’s path.

Since wrath is, in fact, a manifestation of the Power of repulsion, any Power that seeks to preserve the purity of its flow, when it encounters another Power that does not harmonize with it, will inevitably repel that Power. Subjectively, this appears as wrath: any deity of both the “physical” and the “psychic” cosmos, when it meets a Power that does not harmonize with it, repels that Power. It follows that gods are not “wrathful” in themselves; they are perceived as such by minds that are not harmonious with them.

Whereas the destructive actions of angels are a necessary part of the cosmic process, the wrath of gods is more selective: it is less necessary or inevitable and manifests only when no better way exists to reconcile Powers or to resolve the problem.

Here lies the first important lesson for Magi.

The Power of destruction is not always inevitable or insurmountable.

It is activated when the possibilities for evolution have been exhausted and revolutionary transformation is required. To call upon the Power of destruction without necessity is as blameworthy as neglecting destruction when it is truly necessary.

The wrathful face of any Power is its “second” face — in the sense that it comes into play only after the action of the “first”, benevolent face has run its course.

At the same time, one must remember that by changing the mode of its action, a Power also changes its essence — the wrathful face of a god is effectively a different entity from the benevolent face.

This means the Power has different characteristics and a different name. And in this lies the second important lesson.

The authority earned through interaction with the Benevolent face may not work when dealing with the Wrathful face.

Many Magi have fallen victim to a misunderstanding of this fact. By using an approach suited to one face on the other face, they either failed to obtain the desired result or suffered a retaliatory blow.

By understanding these peculiarities in how divine Powers manifest, the Magus can first avoid unnecessary destruction and second differentiate his approach to those Powers, thereby significantly increasing his progress along the Way.

Leave a Reply