Gnostic and Pagan Dualism

Thus, we have seen that dualistic conceptions of the world-process are characteristic of both pagan (in particular, Slavic) and Gnostic thought. Yet this apparent similarity is merely superficial.

According to Gnostic notions, the Deity is absolutely beyond the world and its nature is alien to this universe, which it neither created nor governs and to which it is entirely opposed; the divine realm of light, self-sufficient and remote, stands against the cosmos as a realm of darkness. The world is the work of inferior powers which, although they may indirectly derive from it, in fact do not know the true God and obstruct knowledge of him within the cosmos they govern. The origin of these inferior powers, the archons (rulers), and, more generally, the whole order of being outside God — including the world as such — is the main theme of Gnostic thought, examples of which we will present below. The transcendent God is hidden from all these creatures and is unknowable to natural understanding.

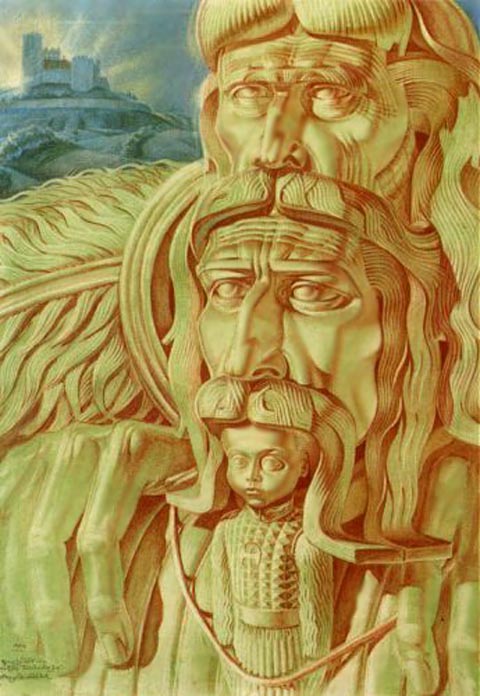

At the same time, according to Slavic pagan conceptions, the Light and Dark principles are coessential, equally close to manifested existence. Belobog and Chernobog were locked in constant struggle: the daytime light dimmed into encroaching dusk, and the night’s darkness was dispelled by the morning dawn; sorrow gave way to joy: after cruelty and envy came a time of selfless and kind deeds. Belobog was portrayed as a wise, white-bearded elder, Chernobog as a misshapen, skeletal “koschei.” Yet the Slavs revered Belobog and Chernobog alike, understanding that it is precisely their struggle that constitutes a necessary condition for the world’s manifestation. The battle between Belobog and Chernobog was usually depicted as two fighting swans — one white and one black — as sacred symbols of good and evil. In the Slavic Chronicle, Helmold described a ritual associated with Chernobog among the West Slavs of his day: “There is among the Slavs a remarkable delusion. Namely: during feasts and libations they pass around a sacrificial cup, uttering not blessings but rather incantations in the names of the gods, to wit, the good god and the evil god, believing that all prosperity is directed by the good, and all misfortunes by the evil god. Therefore they call the evil god in their tongue the devil, or Chernobog, that is, the black god.”

Judging by surviving place-names and folk traditions, belief in Belobog and Chernobog was once common to all Slavic tribes and partly persisted after the arrival of Christianity. According to the Hustyn Chronicle (1070), the ancient volkhvy were convinced that “there are two gods: one heavenly, the other in hell.” Bessarabian settlers, when asked whether they professed the Christian faith, replied: “We worship our true Lord — the white God.” The legend of the two gods survived in the lands of the Don Cossack Host. The Cossacks believed that Belyak and Chernyak were twin brothers who forever follow each person and record his deeds in special books. The good deeds are “registered” by Belobog, evil deeds by his brother. Nothing can be hidden from their piercing gaze, but if one repents, the record of a bad deed will fade, though not disappear entirely — it will be read by God after the person’s death. In the hour of sorrow the brothers become visible, and then Belobog says to the dying man: “There is nothing to be done, the son will finish your deeds.” And Chernobog always gloomily adds: “And he, too, will not complete everything.” The twins accompany the soul into the Other World until the Judgment, and then return to earth to accompany the next newborn until his death.

Note that Gnostic dualism has a pronounced moral character — the Good God is perceived as benevolent, beautiful, whom one should aspire to, whereas the dark god (Ialdabaoth, Satanael) is perceived as absolute evil, from whom one must flee as far as possible. Pagan, “barbarian” conceptions lack such an attitude; in them the White and Black gods are seen as equally necessary and, in general, equally beneficent. Apparently, Belobog and Chernobog are merely particular hypostases of a more general deity (Triglav), reflecting the notion of duality but also the synthetic unity of the Cosmos. Triglav was venerated by all the Slavs, though some peoples worshipped him especially.

Thus, we see a fundamental difference between the early and later attitudes toward the world’s duality: over time the polarization acquires a strongly felt emotional tone — a positive attitude toward Light and a negative one toward Darkness. Apparently, this shift reflects processes that took place in humanity’s awareness of the world-process, its origins and purposes.

The opposition of gods along the lines of Light-Darkness among pagans can also be viewed from the perspective of knowledge. What is unknown is Darkness, what is explained is Light. The struggle of the gods of Light with the gods of Darkness is a struggle for knowledge, for the expansion of one’s own boundaries. After all, everything that the bright gods of pagans possessed, they took either honestly or dishonestly from the forces of Darkness. From this point of view, the struggle for knowledge is the pursuit of Truth, i.e., Absolute knowledge … towards the Macroprosopus, and since initially our knowledge is far from true, we find ourselves in the dominions of the Microprosopus or Demiurge. Here we see that although the dualism of pagans and Gnostics differs, in general it describes the same process.

This is actually a very debatable question. It can definitely be asserted that dualism (the opposition of Evil and Good) is present in Christianity and other monotheistic religions. The essence of paganism for me is primarily a polytheistic worldview and religiosity. Nevertheless, there are many examples of this very dualism – the struggle of gods with titans in antiquity, the giants of the underworld from Asgard in Scandinavian mythology, the Snake of Veles from Perun, the thunderer in our…

Very interesting.