Rephaim – Kings of the Interworld

Among the beings whose contact can mislead and derail a Magus’s path, the apex holds a prominent place in the hierarchy of elementers – Rephaim.

As we have discussed, any unbounded, unordered, unstable space, in which the mind cannot attain stability and where no single world’s laws fully apply, is traditionally called the Interworld.

The Interworld is at once the space of dreams, the space of the afterlife, the dwelling-place of the “grey” spirits, and of elementals.

Despite the Interworld’s extreme instability, there are certain ordered structures — “islands of stability” — sustained by their inhabitants’ collective energy: cities of elementals (Gorias, Finias, Murias and Falias), cities built by elementers-derobing, and the structures of the “grey” spirits (the “watchtowers” described in the visions of D. and Kelley, the “stationary positions” of the “spirits of the air” in the Lemegeton).

Accordingly, the currents of energy that flow through the Interworld are regulated primarily by the Archons, the supreme rulers of that space, but also by the Subcelestial kings, the Dreamkeepers, the Kings of the elements, and the Kings of the Dead.

It is the last group of “rulers” that is particularly interested in inflows of energy from the “sephirotic” worlds, and therefore they often show remarkable inventiveness extracting it.

By learning to manage the Interworld’s currents, especially powerful elementers acquire semi-divine powers and begin to control its processes.

If such beings, moved by care for their kin in the “worlds of the living,” begin to assume protective guardian roles for them, they become tutelary spirits — Manes (or, more precisely, Lares).

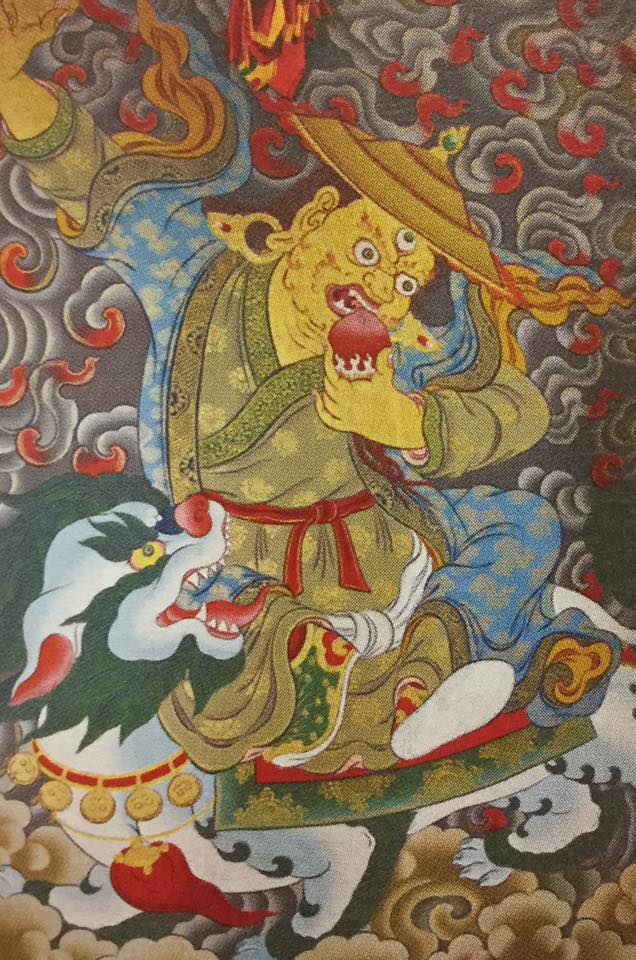

But if an elementer who has achieved considerable power is not guided by care but seeks energy (and/or its “charges” within the Interworld), such predatory beings are called Rephaim (among Tibetans — Gyalpo).

The word “rephaim” (רְפָאִים) appears in biblical and talmudic texts; it stems from the word “רפה”, “weakness“, and the related verb “הַרְפָּיָה”, “to relax”, and refers to certain “mighty” beings or (sometimes) long-deceased ancestors. Note that naming powerful and authoritative beings in this way is a common Near Eastern magical device: by calling someone mighty “weak”, people hoped to diminish his influence over them and thus protect themselves. The Tibetan “gyalpo” (རྒྱལ་ པོ) means “king” and refers to “spirits of evil kings or high lamas who have broken their vows”.

In any case, we are speaking of elementers possessing considerable power and generally hostile attitudes toward humans. It is clear that such a “malevolent temper” is primarily related to the hungry nature of these beings, and their impact on humans is chiefly aimed at obtaining life energy in an activated form. Needing energy both to sustain themselves and to defend against the Interworld’s “cleansers” — the gallu — the Rephaim are not satisfied with merely the “ordinary” utukku strategies, such as the dibbuk.

Their “hunting strategies” are usually more complex and inventive and resemble demonic ones.

Tibetan literature abounds with descriptions of the “machinations of the gyalpo” — such as instigating wars or imposing “false” religious practices.

The Rephaim phenomenon is usually highly impressive and majestic, which can confuse and inspire trust in them. Many Western magi as well as Eastern practitioners have been taken in by the splendor of the Rephaim and have become their feeding grounds.

Interaction with Rephaim is especially popular among necro- and demon-worshippers, who are enchanted by the “gothic” atmosphere of the worlds of the dead.

Being, for the most part, of human origin, Rephaim, unlike “classical” demons, absorb not only the “red” light but also ordinary life energy, and therefore the earliest “diagnostic criterion” of their influence is a feeling of unease, irritability, trembling hands, and other signs of a sharp energy drain that the victim may not even notice. At a later stage, the victim becomes aggressive, and often the Rephaim’s influence ends in insanity.

Those most susceptible to Rephaim are passive, listless people with weak nervous systems, unable to offer resistance to the predator’s enslaving will.

Since the “kings of the dead” are usually interested in large influxes of energy, they can seize entire human communities and provoke wars and conflicts.

Nevertheless, in Tibet there is a long-standing tradition of enlisting gyalpo as protectors and guardians, in some cases quite successful (as, for example, Padmasambhava’s subjugation of Pehar, who became an important guardian of Tibet and its monasteries), in others rather questionable (as the story of Shugden, who still sows discord among Tibetans today).

It would seem that a similar tradition existed among the Semitic tribes, in particular in the form of certain Ugaritic ceremonies, and one can safely assume that relations with the Rephaim did not end well there either.

In any case, a Magus must exercise utmost vigilance to detect and halt the interference of any harmful beings in their affairs, regardless of how wise, powerful, or radiant they may appear. It is precisely the desire to “secure support” or even to “subdue” such mighty allies that proved fatal for many overconfident practitioners.

I do not want to connect anything to anything in any way, but in modern Israel, there are at least two quite specific physical places named “גלגל רפאים” and “עמק רפאים”. The first is a megalithic structure in the Golan Heights. The second is located in the center of Jerusalem.