Afterlife and the “Books of the Dead”

The only thing any person can be sure of is that he is destined to die. If any event of his present, future, or past is merely a matter of probability, the very fact of his coming into the world inevitably implies his eventual departure.

Yet despite the sheer obviousness of this fact, the majority of people are unprepared either for death itself or for what comes after it. The same sense of time and prolongation which is the most powerful distraction, drawing one away from perfection in every moment of life, also draws one away from the sense of the inevitability of death. Thus most people live foolishly and die just as foolishly.

Magi and priests always understood both facts — the inevitability of death and people’s unreadiness for it — and therefore were concerned with creating adequate descriptions, maps, which, by describing what happens to the mind in the afterlife, would help one, despite the shock and the mind’s unpreparedness for that state, pass through it safely.

Although all cultures and all religions produced such “maps,” two of them are the most fully developed: the so‑called Egyptian and Tibetan “Books of the Dead.” It should be said that neither of them is actually called a “book of the dead” — that phrase was applied to them; the original sources bear more precise and goal‑fitting titles respectively: the “Book of Going Forth into the Daylight” and the “Book of Natural Liberation through Understanding in the Bardo.”

Both books, in their original conception, have a single aim: to help the mind return to its “highest” state, which the Egyptians called the “pure spirit,” the “Akh,” and the Tibetans the “nature of the Buddha.” Therefore a “complete” and most successful passage through the afterlife according to each Book’s map of the “Books” means precisely the mind’s transition into the boundlessness and the unconditioned nature of the absolute spirit. However, the authors of the “Books” understood well that this task would be unachievable for most of the dead, and so they ensured that someone using a Book’s map, even if he did not reach the ultimate goal, would secure a “favorable” fate in the afterlife.

The “Egyptian Book of the Dead” arose around 2.5–3 millennia BCE, although it survives only in versions from the 7th–6th centuries BCE, and consists predominantly of hymns and spells recited over the body of the deceased during burial ceremonies, as well as inscribed on tomb walls and placed in sarcophagi with mummies for use by the “dead themselves.”

Later other similar texts appeared — the “Book of Amduat,” a number of “Books of the Gates,” the “Books of the Caverns” — which served the same purpose and reflected the views of different priestly schools on the afterlife.

Strictly speaking, the “Book of Going Forth into the Daylight” can be considered to comprise three large groups of texts: 1) hymns to the gods and chants recited “on the way” to the afterlife; 2) hymns and spells describing the journey into another existence; and 3) spells and hymns necessary to pass the Netherworld Judgment and obtain a favorable outcome. These scrolls are accompanied by a group of texts describing rituals intended to preserve the mummified body and “memorial” texts recited long after death.

To make sense of this “map,” let us recall once more what the Egyptians said about the mind after death.

For the Egyptian, the human being was a unified whole, composed of several “aspects,” “layers,” or, as people often (and inaccurately) say now, “souls,” and for successful and complete existence all these layers in their interaction were considered necessary.

The first aspect is the physical body, the “Sah.” The body as vessel and instrument was regarded as a very important component, “binding” together and providing support to all layers of the being.

The second component is the “etheric body,” the “Ka” — also a “supporting” structure that upholds the mind when the Sah is inactive (for example, in dreaming or in the afterlife).

The third component is the “body of desires,” the “Ba,” a kind of the person’s “essence,” which is both source and product of drives, motives, desires, feelings, and sensations. It was believed that the Ba separates during dreams and is also capable of passing from body to body.

The fourth element of the being is its “heart,” the “Eb,” which in turn was thought of as threefold, consisting of the “heart of thoughts” (or, more precisely, the heart of intentions), the “heart of causes,” and the “heart of meaning.” The point is that the Eb is the “weaver,” a “system-forming” component of the being, uniting all its manifestations into a single whole.

The fifth component (or, if the “three hearts” are counted separately, the seventh) is the “spirit,” the “Akh” — the pure and unstained ground of the being, situated beyond limits and beyond embodiments, supporting them all and being integral to them.

In addition, important components of the human complex were the name — Ren — the carrier of information about individuality of the being’s manifestation, a kind of “anchor” anchoring the incarnation in concrete reality, and the shadow — Shuit — serving as a kind of “observer and recorder of a person’s deeds.”

In the afterlife it was the deceased’s Ka and Ba that were active, although the passage required an intact and pure Sah, and the condition of the Eb was important for determining the outcome. Finally, in the “ideal” outcome the being identified with its Akh and flowed into the divine currents of the mind.

The afterlife began with a semi‑conscious existence that lasted seventy days — the period of mummification of the body — and was described as the “ascent onto the Barque of Ra.” During this time the mind is in an unstable condition, periodically returning to its abandoned body and then falling into brief trance states. Only after the completion of mummification and the burial rites does the actual journey through the interspace begin. Thus the funeral rite in Egypt was, in effect, a rite of “resurrection,” a re‑union of the disjoined components of the person into a whole in order to effect the transition.

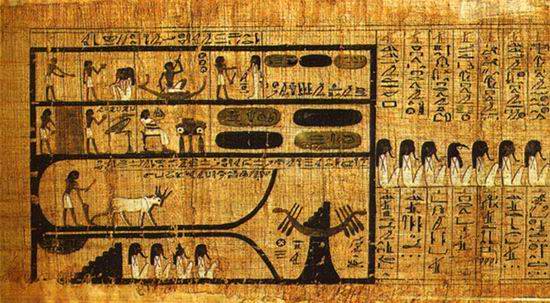

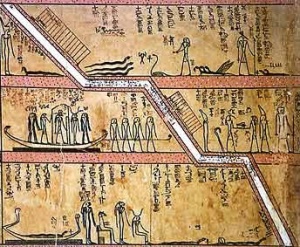

The entire space of the afterlife — the interspace, or the “Duat” — was divided into three distinct regions according to the states of the deceased’s mind:

1) The “West” or “Amenti” — the first space into which the mind, centered in the Ka, passed immediately after burial. This space, also called the “Gates of the House of Osiris,” was in fact the “entrance” into the interspace of the Duat. Successfully overcoming it meant losing connection with the “physical” world and entering the Interworld safely. These gates were guarded by two stern sentinels — the “Watcher over the Fire” and the “Many‑Faced One who bows the spirit to the earth” — assisted by a Messenger, the “Giver of Voice.” The sentinels ensured that the activity of the mind (its “fire”) and its inertia (“earth”) remained in balance; in other words, the Gate was crossed by a mind ready to decisively leave behind the charms of the forsaken physical world. Accordingly, failure to overcome the Gate is described as the “loss of Sah,” that is — the loss of one of the components of one’s wholeness, and thus the need to restore it, which meant being cast into a new incarnation.

2) If Amenti was successfully overcome, the mind entered the next intermediate space called the “Sky of the Gods,” “Hart‑Nitr.” This space, in turn, included a series of regions.

The first stage of traversing Hart‑Nitr was the Lake of Fire, around which two winding paths ran. On these paths the mind was ambushed by numerous predators, malevolent spirits, and monsters, which could be passed only by knowing their nature and names. If the mind were defeated, it “lost the Sah,” that is — it fell back into a new incarnation. Thus at this stage the firmness of the lessons acquired in embodiment and the readiness for the next evolutionary step are put to the test.

Having passed this stage, the mind arrived at the “Field of Hills,” where it had to cross fourteen hills corresponding to fourteen different states of its Ka. This overcoming constituted a test of the Ka — the stability of the being’s “etheric body.” Accordingly, failure to surmount the hills led to the “loss of Ka,” that is — to rebirth not only in a new “physical” body but also with a new Ka.

The next stage of the journey was the “Road of Dwelling Places.” It represented a long and very exhausting path, along which seven “dwellings” — “Arit” — served as places of rest. To enter each dwelling it was necessary to pass three gates, each guarded by its Gatekeeper, whom one had to know by name (for knowing a name gives power, that is — to be able to master that power). Each arit signified one of the possible states of the Ba, and thus passing through these dwellings corresponded to a test of the resilience of that component of the being. If one erred, one could lose one’s Ba in one of the arit, which again meant a fall into a new incarnation, serving as the “re‑creation” of the Ba.

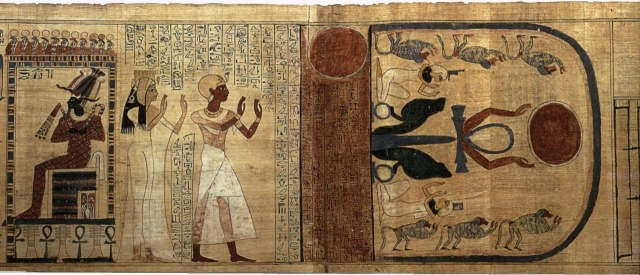

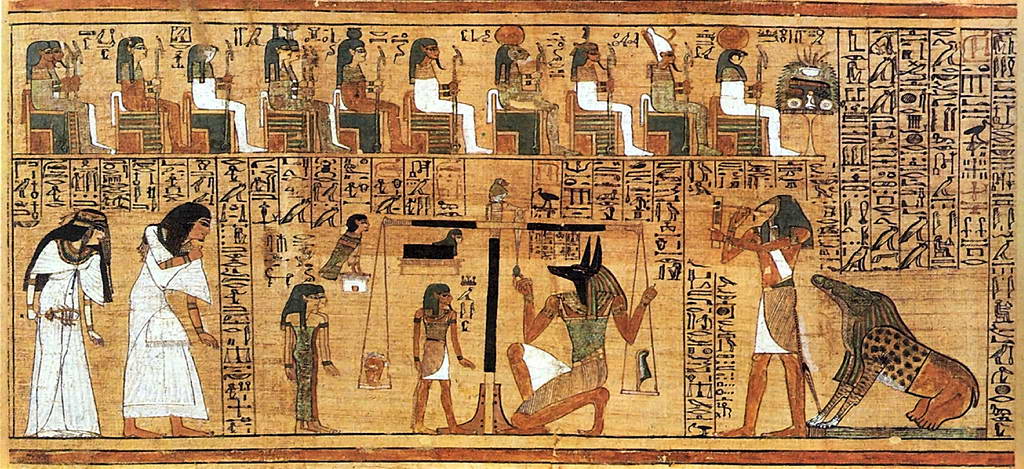

Having passed the “tests” of strength and perfection of the “lower” layers of its complex, the being entered the next region, called the “Hall of Maat” (“Shuma“) or the “Hall of the Two Truths,” which served to examine the heart — the Eb. To enter the Hall one also had to name the Guard, the Gatekeeper, and the Messenger, and recite a whole series of spells.

At this stage two trials take place — first the “weighing of the heart” — the well‑known procedure in which the “weight of the heart” — the Eb — is compared with the “weight of truth” — the feather of the goddess Maat. The Eb must be “true,” neither lighter nor heavier than that “feather”; otherwise the “heart” is handed over to be devoured by the terrible monster Ammit, which meant a fall into lower levels of rebirth. At this same stage the “testimony of the Shuit” also occurs — that is, an examination of the shadow of the mind. If the “weighing” is passed and a “verdict of acquittal” is pronounced, a second trial follows — the judgment of Osiris. At this final stage the last determination is made of the degree to which the mind corresponds to its “true nature,” the Akh, and if such correspondence is confirmed — the mind is admitted to the third layer of the afterlife.

3) Fields of Reeds (Fields of Iaru). This is the abode of pure spirits, a realm of endless light and bliss.

Thus the journey through the Duat, fraught with many complexities and dangers, led the mind from its private, limited state to the boundless radiance of the spirit. In this respect the “Egyptian Book of the Dead” offered a description of this journey that moved from the lower layers of mind to ever higher ones, that is, it described the afterlife in its “evolutionary” direction. As we will see later, in the “Tibetan Book of the Dead” the process is presented in the opposite direction.

Leave a Reply