Afterlife and the “Books of the Dead”. 2. Bardo Todol

Since, regrettably, there are no living ancient Egyptian priests left, the teaching of the Book of the Seeker Toward the Light has faded into obscurity and is perceived by the popular consciousness as somewhat archaic. At the same time, thanks to the active efforts of living Tibetan lamas, the concepts and maps presented in The Book of Natural Liberation through Understanding in the Bardo are actively studied and have aroused widespread interest. This tendency is not entirely fair, because the two “Books” are largely similar, and their authors — undoubtedly — understood well what they were writing about and were guided by similar benevolent intentions. Nevertheless, despite their ideological similarity, there are both technical and doctrinal differences between the two Guides. The Tibetan Book of the Dead, the Bardo Todol, originated in Tibet in the eighth century, and it is attributed to the “Precious Master” Padmasambhava, who, however, concealed the text until people were ready to receive it. That readiness came only six centuries later, when the “Book” was found and published by Karma Lingpa. In the West, the Bardo Todol became known after 1927, when its first English translation was done by Kazi Dawa-Samdup, edited and published by Oxford professor W. Evans-Wentz. Since then discussions of the “Book” have continued; new translations and fresh interpretations continue to appear. Despite its primary purpose — recitation over the deceased — the Bardo Todol can (and should) be studied during life to prepare the mind for existence in the intermediate state.

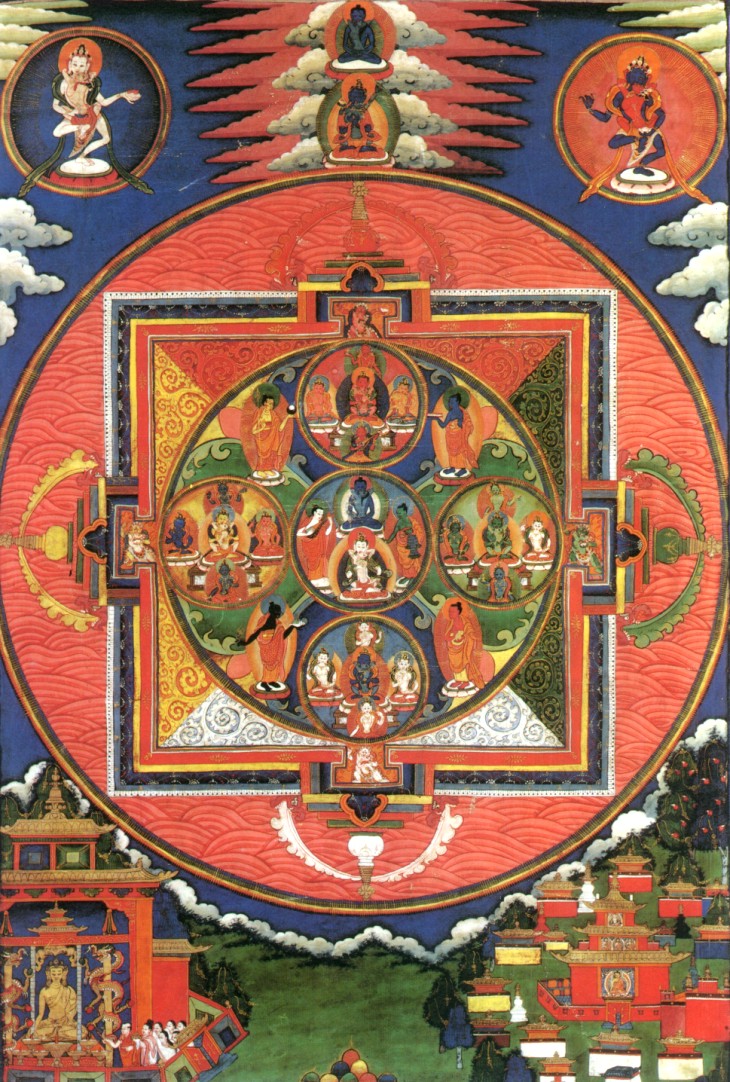

In general, the Buddhist view of the interspace is quite broad: the word “bardo” describes any state between two “transitional” points, and, besides posthumous bardos, life itself (as the interval between birth and death), sleep, and trance (samadhi) may be regarded as bardos. Formally, it is so; moreover, if one approaches the description of intermediate states as the mind’s dwelling in a particular interstitial quasi-reality — the Interworld — then it seems we encounter bardos frequently and everywhere. The main message of the Bardo Todol is the same as that of the “Book of the Seeker Toward the Light” — to help the mind, dwelling in the intermediate state, discover and realize its “higher” nature. It is precisely the high instability, and therefore the plasticity, of the mind in the interspace that makes it highly receptive to such instructions. Both guiding traditions believed that, with proper orientation, the mind, freed from the constraints of the “dense body,” could make a great evolutionary advance in a short time. Like the Egyptians, the Tibetans divided the afterlife into three distinct stages, three bardos — the Bardo of the moment of death (Chikhai bardo), the Bardo of the reality of the interspace (Chönyid bardo), and the Bardo of preparation for a new embodiment (Sidpa bardo). However, while in the “Book of the Seeker” these states are considered in the order of “increasing,” in the “Book of Liberation” they are presented in the order of “decreasing” intensity, and, as C. G. Jung noted, the Bardo Todol treats the journey of the mind in an order “reverse of initiation.”

The reason for this ideological difference lies in the differing emphases of the authors of the two Guides: the Egyptian priests, focused on being, saw that the deceased mind undergoes a gradual process of disidentification from its embodied reality, whereas Padmasambhava, whose focus was on the mind itself, pointed to the “condensation,” the “darkening” of the nature of that mind from its “center” toward its “periphery,” and therefore insisted on the “return to the center.” Accordingly, the “Book of the Seeker” says almost nothing about the existence of the mind in the higher spheres in which it dwells between death and the funeral. It does, however, assert a clear “divinity” of the mind in this period, its identity with the world spirit; the deceased’s words at this time are divine:

“I am Atum, being one. I am Ra at his first rising. I am the great self-created one…”

For the Bardo Todol this very moment (Chikhai bardo) is the most favorable for liberation: the light perceived at this stage is the light of infinity; entering that light and discovering one’s identity with it, the mind immediately reaches its highest state (liberated into the Dharmakaya). Yet both Egyptians and Tibetans clearly understood that for the ordinary person, with the usual identification of self as a finite and limited being, this primordial radiance is too intense, too frightening, and most likely the deceased mind will shrink from dissolving into it; hence a long passage through the intermediate state is likely. If the mind does not enter the Clear Light at the beginning of the Chikhai bardo, then in the second stage of this intermediate state it fashions for itself an “illusory body,” within which it makes its journey through the intermediate state. The Egyptians, as we have already seen, called this stage a “resurrection in the Duat,” while the “Book of Liberation” speaks of entry into the reality of the interspace — the Chönyid bardo.

It is at this stage that the journey occurs which the “Book of the Seeker” described as encounters with numerous guardians, gatekeepers, and messengers, and which the “Book of Liberation” interprets as the “space of karmic visions.” In any case, the mind must confront the forces and impulses it has created, face its dead ends, fears, and its shadow. The Bardo Todol describes these as phenomena in consciousness first of peaceful deities, pure and enlightened visions of the mind, then of wrathful Herukas, pure energies terrifying in their power, and thereafter of other, less exalted entities — “keepers of knowledge” (vidyadharas), goddesses of passion — gauris, flesh-eaters — pisâcas, destroyer-goddesses ishvaris. This stage is an attempt by the mind to reconcile within itself various contradictory and disharmonious forces created during manifested life. In effect, it is the same self-examination that the “Book of the Seeker” described as a journey through the Duat with its lakes of fire, hills, and caverns. At the same time, the Bardo Todol insists that at any of these stages, upon recognizing itself as the source of all manifestations, the mind can break free from the snares of the intermediate state and attain liberation. The Egyptian priests apparently did not believe such chances were likely for the ordinary person, and therefore advised the mind to keep moving onward, merely resting temporarily in the Arits. The Chönyid bardo concludes with an encounter with the Lord of the Dead and his retinue — Shinje (Indian Yama) — and this meeting is clearly analogous to the Judgment described in the “Book of the Seeker.” Here the Bardo Todol becomes far more detailed than the “Book of the Seeker,” since it proceeds to consider the possibilities of future rebirths and strives to make them as favorable as possible.

If the mind has not yet identified itself with all the currents and visions that appeared in the Chönyid bardo, it enters the final stage of the interspace — preparation for a new embodiment. This stage is called the “Bardo of Choice,” the Sidpa bardo. At this stage the deceased must, as far as possible, secure a favorable rebirth, although the possibility of escaping the cycle still remains. Thus, according to the Bardo Todol, the chief task the mind must accomplish in the interspace is the discovery of itself as the source of all the auspicious and inauspicious currents, powers, and agents perceived in that state. Such discovery moves the mind from a limited, “darkened” self-identification to its infinite and unconditional nature. If this “maximum program” is not fulfilled, then the mind of the practitioner must devote all its efforts to resisting the “karmic winds” that carry it toward rebirth and attempt to climb the evolutionary ladder as high as possible. As we have already noted, one must clearly understand that both the “Book of the Seeker” and the “Book of Liberation” are not mere speculations or world descriptions; they are practical guides, composed not by philosophers and not for philosophers, but by practitioners based on concrete empirical experience and intended to provide practical help in overcoming the difficulties and dangers of the interspace. Therefore the analogies and the differences between the two texts should be considered primarily from a practical perspective. Indeed, a mind rigidly attached to a particular map and “prepared” for it, when confronted with mismatches between map and experience, may be thrown into greater confusion than by “direct perception.” Hence, before using any of these texts as a map, each practitioner must carefully analyze that map, especially how it corresponds to one’s mind, its peculiarities and emphases. If the mind is oriented toward a rapid liberation from the cycle of rebirth, ready to renounce all its comforts and attachments, it will find the Bardo Todol scheme more useful. If, however, the mind’s primary aspiration is its evolution, gradual purification and perfection, it will benefit more from the Egyptian system.

Hello, esteemed Enmerkar! I am interested in your opinion on the practice described in Timothy Leary’s book “The Psychadelic Experience: A Manual Based on the Tibetan Book of the Dead” for self-improvement.

Here is the translation of the text into English:

—

This concerns not only the “datura”…

but all “psychedelics”… 🙂

**“Datura”**

The girl has had her fill of datura,

She feels sick, her head is aching,

Her cheeks are burning, she’s nodding off.

But her heart feels sweet, sweet, sweet:

Everything is unclear, all a mystery,

There’s some ringing from all around:

Not seeing, her gaze sees another,

Wonderful and unearthly,

Not hearing, she clearly catches the sound

Of the delight of celestial harmony –

And the weightless, bodiless

Was led home by the shepherd.

In the morning they built a coffin.

They sang over it, offered incense,

Her mother cried… And her father

Covered it with a rough wooden lid

And took it to the graveyard under his arm…

Is this really the end of the tale?

**Ivan Bunin**

—

Let me know if you need anything else!

Namaste!

While reading ‘EKM’, an internal dispute and misunderstanding arose concerning the following point – it turns out that all parts of the Personality, such as Ka, Ba, Ah, after the death of the physical body – Sah, seem to separate, like some kind of transformer. For the first 70 days, they are in different places altogether, and then they come together, and the Afterlife journey begins, consisting of various stages. Interestingly, at each stage, there are tests for the individual parts – Ka, Ba. And if it does not pass, it returns for a new incarnation, while the other parts of the personality remain somewhere out there…

Please explain this moment of separation – or perhaps I do not understand something.

The second point is related to magicians and priests, and not ordinary people. If the initiates understood the general picture of the afterlife, realizing that the physical body had fulfilled its purpose, then why so much attention, time, and energy were spent on creating and maintaining a mummy, as well as proper care and respect? Why all this if they knew that the body had served its time, and a new body would be given in a new incarnation? And the unclear concept of subsequent returns of Ka and Ba to Sah for the supposed resurrection…

In general, either over so many centuries something has been lost, or the magicians intentionally left out many details, or the translators and interpreters have distorted a lot.

The separation of the being, its disintegration, constitutes the essence of death as a ‘restructuring’, a regrouping of components – in order to assemble a new system from various elements, the old one must first be destroyed. In this process, each component remains exactly where it has always been, in its ‘environment’, its nature; only their connection and unity are destroyed. Actually, something similar, only on a smaller scale, happens daily during sleep – the body seems to be ‘on its own’, and consciousness – ‘on its own’, although neither the body nor consciousness goes anywhere – only their mutual coordination is disrupted. We have already discussed this: https://enmerkar.com/en/myth/the-unweaving-of-ea

Regarding the second question – we also discussed it – https://enmerkar.com/en/way/fixation-of-souls-flight-from-gilgul The preservation of the mummy, the physical body – is the preservation of a support for consciousness at the level of existence it has achieved.

Well, where is the consciousness located during such separation, in which of the bodies-places?

Consciousness is present in all of them – at each of the corresponding levels. One just shouldn’t cling to the category of time and ‘simultaneity’, especially when it comes to the Interval.