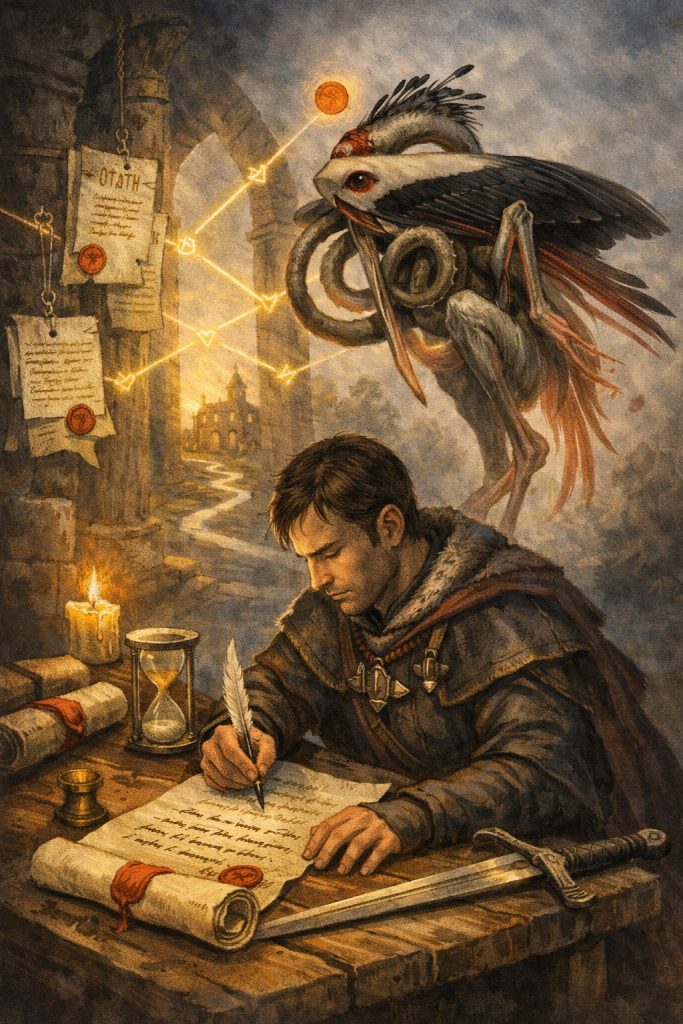

Shax and the Betrayal of Vows

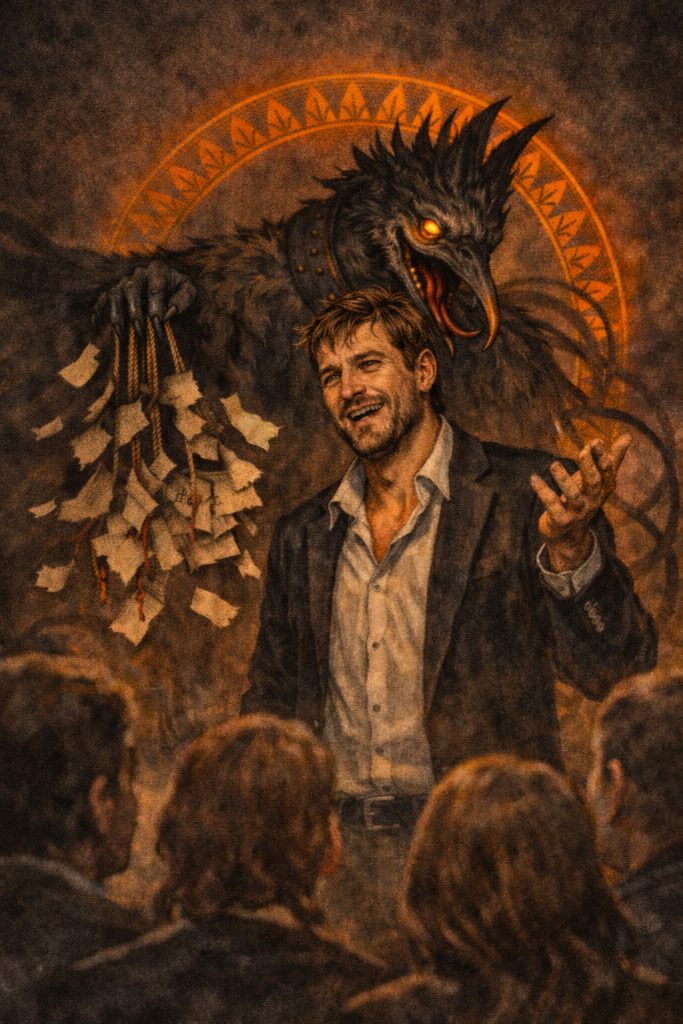

We have already noted that one of the most dangerous — and often overlooked — forms of moral dissolution, the loss of one’s centre in the search for support in others, is the betrayal of the bond with uttered words: the falling out of the very hierarchy of logos, frequently instigated by the underestimated demon Shax.

Indeed, modernity seems to have forgotten the inviolability of oaths, the firmness of vows, and the value of promises. Breaking a promise is often dismissed not as a moral failing but as a minor peccadillo. The dictum “deeds matter more than words” can sound true — unless one remembers that, in the register of Magic, words are as potent as deeds.

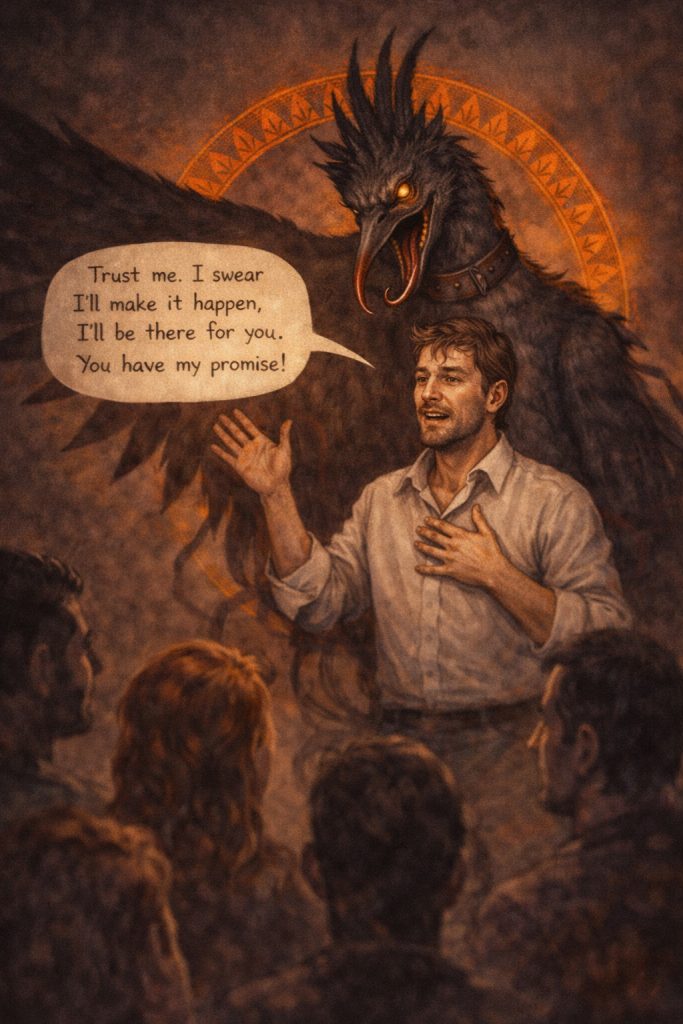

Yet those who invoke “deeds over words” often do so to evade responsibility. Shax thrives on the habit of treating a promise as provisional, a draft, and one’s own “yes” as mere polite formality that can be replaced tomorrow.

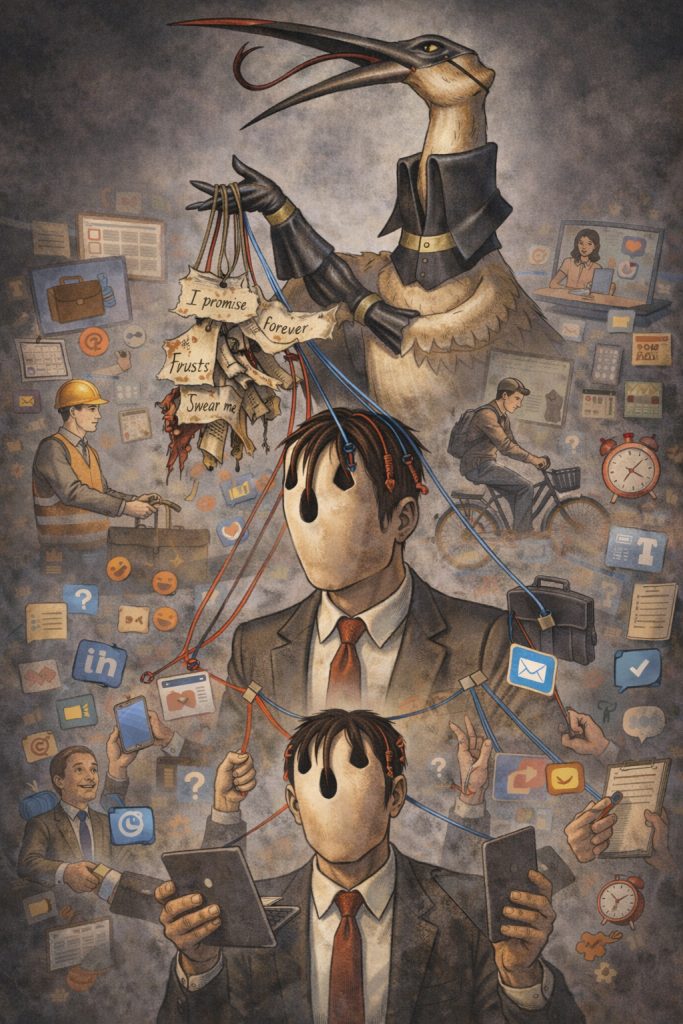

A promise anchors the future: it marks the point toward which the will turns, even when moods shift or circumstances demand greater exertion. In traditional societies a vow gives the world certainty — it builds fixed currents within the raging ocean of possibilities. Today, however, speech has largely lost that binding role: words pour forth in a torrent that creates an illusion of being. When words are abundant, each one is devalued; promises inflate and are traded for transient advantage, ornament, or the affirmation of self.

Shax’s matrix in consciousness often begins with the desire to be liked, to avoid awkwardness, to save face, to buy time — a promise used chiefly to manage the other’s attitude.

When words become inconvenient, they are neutralised by stock excuses: “I meant something else,” “You misunderstood,” “Circumstances changed.” These formulas do not cancel a statement so much as dissolve it into an endless fog of clarifications. A soft habit of shirking duty forms without inner resistance, and this is what sustains the destructive pattern: conscience grows numb because the mind finds plausible detours.

Shax gains influence when the word is treated as mere property — an object in the pocket to be plucked or hidden at will. Not coincidentally, this demon belongs to the great retinue of Asmodeus (and to his junior subject, the King of Lust, Beleth). Under this detractor’s sway a promise becomes an item to be used or shelved, granting a feeling of control while eroding reverence for the logos as the ground of being. Speech ceases to be creative and becomes a secondary instrument serving transient interest. A faint weariness of solemn formulations arises, a reluctance to pledge, an inclination to “promise nothing” to avoid contradiction. Thus Shax leads one to see promises as perilous folly and fidelity as an empty word.

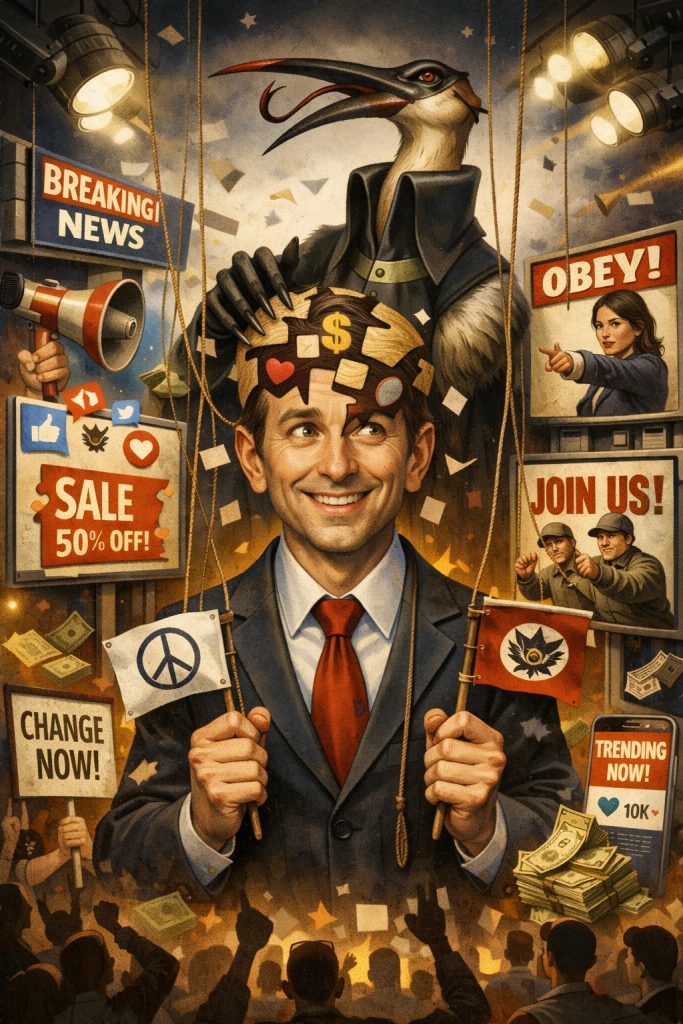

Today this shift is conspicuous: public speech meets growing scepticism. People say “we cannot even agree on facts,” and the milieu itself devalues reliance on words. When the surrounding discourse is unreliable, one is tempted to treat one’s own promises as conditional, mere instruments of persuasion. Shax simply amplifies this drift and turns it into the mainstream.

There is a tendency to declare that “it does not matter what vows were taken; only actions count” — as if vows belong to the past and deeds to the present. Deeds are visible, measurable, praiseworthy. A vow can seem an unnecessary luxury, a mere ornament that does not alter the “here and now.”

So an apparently righteous act becomes a universal pardon. Having done something good, one feels declared decent, and it becomes easier to regard promises as negotiable details to be postponed, softened, or evaded. The mind comforts itself with: “I am basically a good person and act rightly.” Vows cease to be the axis of a path and become optional gestures that require no lasting fidelity.

Under this detractor, moral correctness is mistaken for the correctness of motive. One may do much good, utter worthy slogans, align with “the good,” and conclude that vows are superfluous. Internally, however, this allows small betrayals of the word presented as “flexibility.” Shax divides consciousness into an outwardly righteous façade and an inner realm where words are devalued, edited, revoked without shame. The more social approbation for visible deeds, the easier it is to miss that one’s speech has lost contact with one’s essence and destiny.

Shax is silent about the many motives that can produce right action: habit, calculation, fear, the wish to appear worthy, image management, group pressure. These may yield “worthy” deeds but do not fortify the centre of consciousness. Vows, by contrast, establish that centre: they bind the will to a chosen logos in advance, before wavering and self-justification.

He exploits the gap between visible correctness and inner fidelity. First he substitutes promises with acts, then he erases their meaning. One remains “seemingly right” while the capacity for keeping vows withers. Outward decency can conceal an inner dissolution of continuity — the thread that makes a person the same through time. Such consciousness rejects causality; implicitly it denies that the present is shaped by the past. Sooner or later fidelity will be required, and situational “rightness” will not suffice.

In our world, under a double pressure — demonic and archontic — the absence of a firm inner centre is promoted, because a centred consciousness sells poorly, resists governance, and will not be easily integrated into social systems. As we have discussed, attention is currency. Platforms profit from the easily switched person: today one identity, tomorrow another; today sworn, tomorrow erased; today outraged, tomorrow mollified. Interfaces and algorithms accustom consciousness to live without an axis: their optimisation extends feed time and increases interaction frequency, keeping people in a microreaction mode rather than a sustained inner line.

This system rewards a pliable identity. Seen as a perpetually rewritten “project,” the self readily purchases new symbols, roles, languages, and attachments. Human life becomes behavioural data and “prediction products” sold to those who want to know what we will do “now, soon, and later.” For that market, a person without a firm inner resolve is convenient — predictably reactive. The world rewards those who promise swiftly and switch swiftly, who retain charm and apparent righteousness even after canceling their words.

Social and occupational structures intensify this short-term self. With increasing platform and gig work, life is sliced into short projects, side gigs, quick ties, and rapid role changes. The inner axis demands effort; many deem it impractical, while nonconformity becomes a liability. Thus the centreless adapt more readily, agree sooner, and withdraw more quickly.

In an age of flux, steadiness is mistaken for stubbornness, and inner integrity for inertia. Adaptability is necessary, but without an inner core it degrades into mere accommodation. A stable centre allows one to change while preserving identity; its absence permits change that betrays the self.

Modern culture trains us to live as if words were drafts and promises social lubricant. In that climate the demon of devalued speech readily allies with platform profit, the din of the age, and the habit of retreat without inner resistance.

The remedy begins with relearning to speak less and more precisely — to speak so that a promise implies obligation. Where promises are irrevocable, they stitch the world without gaps or leaks, giving it form, measure, clear terms, and intelligible costs. The word becomes again a means to build a future not imposed by predators or parasites; it renders the world an ordered stream rather than a passive swamp stirred by interested consumers. This is the reclaiming of speech’s original dignity: the promise should be rare, weighty, alive — that which creates and guards the centre of consciousness and prevents it from dissolving into a chaos of affects.

Thank you.

Thank you, Master! Very relevant article.