Fixation in Ignorance

Since the ordinary state of mind, full of frustrations, limitations, and imperfections, is rightly perceived as negative and painful, the natural reaction is to try to reduce this suffering. In fact, it is precisely the reduction of suffering caused by the imperfection of mind and the environment of its manifestation that most paths of development are aimed at — both in the “spiritual” and in the “social” planes.

Since suffering is a purely mental category, one type of response to pain, the simplest and most obvious way to reduce it, is precisely a restructuring of mind, changing its reinforcement systems and response patterns. At the same time, the desire to reduce suffering is often expressed only in addressing defensive mechanisms of the psyche, without its internal reordering, without weakening the causes of suffering, the factors that cause it. In other words, all the elements that trouble the mind, all its pathological manifestations and vulnerabilities, remain in place — but the mind is “trained” not to notice them, learns to ignore them and to become “thick-skinned.” Instead of harmonizing mind and the environment of its manifestation, people often merely build a more comfortable way to exist for a sick mind in a sick environment and consider their task accomplished.

Clearly, it is possible to restructure the reward systems in the brain, and it is not that difficult to achieve a state in which both one’s own suffering and the pain of the world are no longer perceived as disturbing or uncomfortable experiences. A huge number of meditative and psychological training techniques work in exactly this way: the brain switches from adrenergic regulation to serotonergic regulation, learns to produce the required amount of reinforcement on its own, and settles into a state of calm.

For example, during stress the brain’s stress-response system is activated, which includes the release of the hormones cortisol and adrenaline. This reaction can lead to changes in the brain’s neurotransmitter systems: stress reduces the level of neurotransmitters such as serotonin and gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA), which are involved in regulating mood and reducing anxiety. This is what leads to feelings of depression, anxiety, and irritability under adverse circumstances. By contrast, during meditation a relaxation response is triggered; meditation increases the level of serotonin and GABA, which can help reduce anxiety and promote a sense of calm and well-being. In addition, meditation increases the activity of the dopamine system, which is involved in regulating motivation and reward, and may contribute to the sense of well-being and pleasure that many people experience during meditation.

Moreover, regular meditation practice can lead to changes in the structure and functions of the brain that can persist for a long time: an increase in cortical thickness in brain areas associated with attention and emotion regulation, as well as changes in the activity of systems that regulate “mind-wandering” and self-referential thinking. Obviously, such restructuring significantly increases internal comfort, reduces anxiety and frustration, but at the same time it also reduces motivation and decreases the overall alertness of the nervous system.

In other words, a person who regularly practices mind-“calming” techniques becomes blissful, content, happy — but inert and internally passive. He “ascends from samadhi to samadhi,” and begins activity only in order to further increase the level of internal reward, to raise inner comfort. For example, people who regularly practiced meditation show greater activation of the ventral striatum, a key area of the brain’s reward system, in response to reward-related stimuli, compared to people who did not practice meditation. This heightened activity indicates greater motivation to engage in rewarding activity, and less motivation for activity that does not bring immediate reinforcement. One could say that a person “soaked” in “calming” practices is more oriented toward “productive” activity, and less toward struggle, toward that which brings neither victories nor joys.

Thus, although people strive for happiness and avoid suffering in everyday life, when they try to apply this same logic to the development of their awareness, they often make mistakes and create a new dependency. Despite the fact that the true state of mind is not associated with suffering, one should not confuse this state with a simple sensation of pleasure. The indicator of the correctness of our understanding of the natural state of mind is the stability and balance of our stream of thoughts and feelings. If we simply strive for bliss, we can get entangled in our desires and constantly seek ever more subtle pleasures. But if we strive for naturalness, we have a better chance of avoiding such dependence.

On the one hand, of course, reducing suffering is the most important task of development, and a person who has reduced his inner anxiety lives a far more comfortable life. But on the other hand, the level of his mind remains unchanged: he does not overcome his impasses, but only bypasses or ignores them; his inner problems remain — just well fed and lulled to sleep.

Unfortunately, observations of the inhabitants of monasteries and ashrams show that a significant part of them are outwardly peaceful, calm, but inwardly harbor self-satisfied egos, easily falling into dissatisfaction or even aggression if their holiness and achievements are questioned.

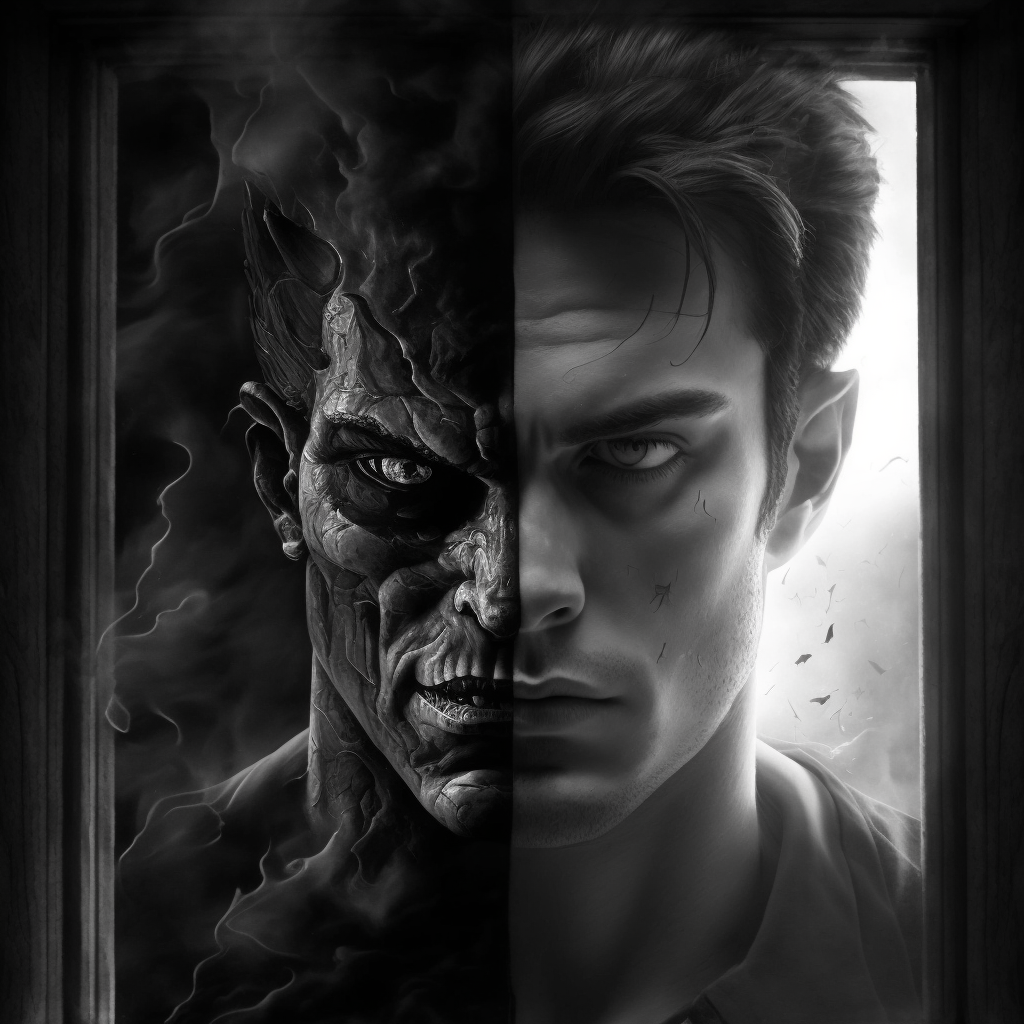

Instead of working through their negative energies, reactions, and manifestations, many such “practitioners” simply divide their mind into two parts — “holy” and “dark,” and firmly lock the latter away. As a result, their inner demons, deprived of even basic oversight and control (they are ignored, denied), develop in a completely unpredictable way and, even if they are not released in the current life, they resurface after death or in subsequent incarnations, significantly increasing the overall level of darkness in the world.

Deprived of the driving imbalance, mind does not attain perfection; on the contrary, it is “preserved” in its “spoiled” state, masking deep rot with outward well-being. And many “spiritual practices” are such “preserved ignorance,” in which darkness is present in a latent, but mighty and living form.

It turns into a paradoxical situation: “holy” and “righteous” practices in fact act as channels for darkness. No wonder they say that “more demons live in monasteries than in brothels,” and that what in the modern world is commonly called “spirituality” more often impedes the development of mind than helps it.

The sad truth is that substantial evil does not disappear simply by being ignored; you cannot destroy it by “pumping” the brain with serotonin and mind with bliss; the only way to get rid of it is to meet it face to face, and transform its energy into an uncorrupted form. And then, when the illness is hidden or masked, it will first have to be identified, brought to the surface, which, of course, will be very painful, and all the efforts spent on bliss will go to waste.

Dissatisfaction, frustration, mental unfreedom are negative phenomena from which, of course, one should free oneself; however, the path to liberation from them is not in ignoring, not in “sweeping them under the rug,” but in actively working through and integrating the energies that feed them — into the whole of one’s being.

And just as one should not cultivate and sustain destructive states of mind, one should not get carried away with the “positive” pursuit of subtle pleasures. Any bias toward one extreme only entrenches disharmony, and even if everything looks blissful and decent, it does not mean that it really is so.

Damn, how accurately you conveyed concepts that I could not manage to form into words!

Thank you for the clarity of thought. Once again, a timely article reinforces the findings I had reached. Finding peace in soft medicinal solutions (artificial serotonin and so on) made me mold a feeling of powerlessness, a loss of joy in overcoming. There is much to think about and take into consideration.

I was amazed for some time that in the church, demons are clearer than in the subway. At least they differ in the depth of ‘immersion.’ But even so, the template phrases from the comfort zone of parishioners still cut the ear.