Belial’s False Unity

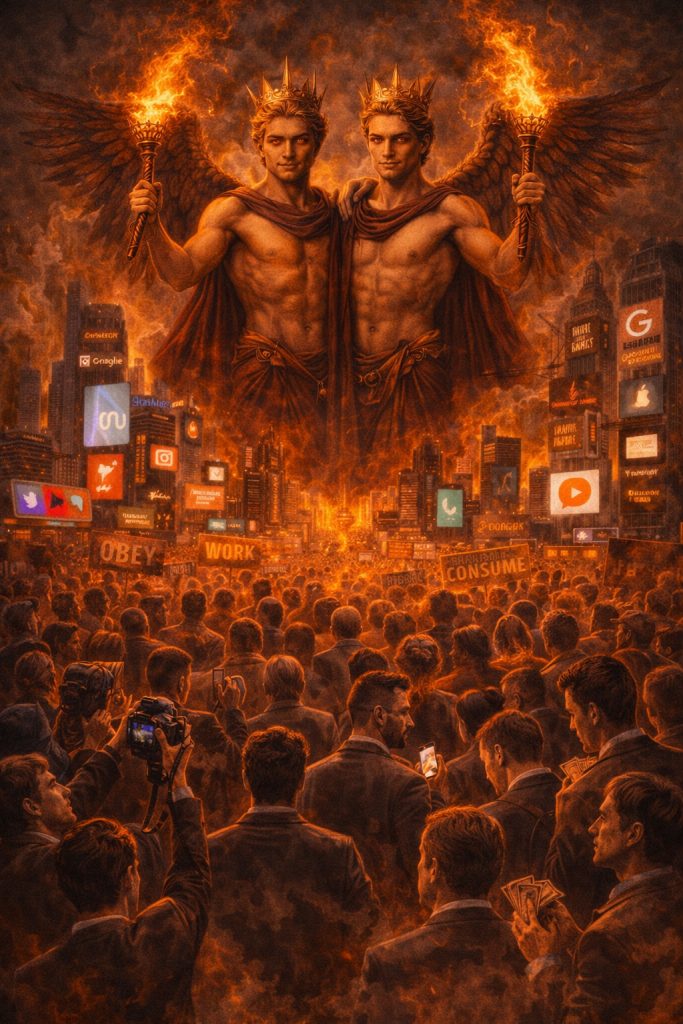

As discussed repeatedly, the true ruler of most contemporary societies and social structures is the King of Wrath — Belial. We have also noted that the paradox of this situation lies in the fact that the most important (and often the only) principle holding such structures together is precisely a force of repulsion lacking balance: the logic of dividing people into “us” and “them.” Bonding within these groups does not arise from members’ mutual compatibility or attraction, but from a drive to distance themselves from the ‘other’, and therefore — to a large degree — rests on more or less conscious hatred and aggression.

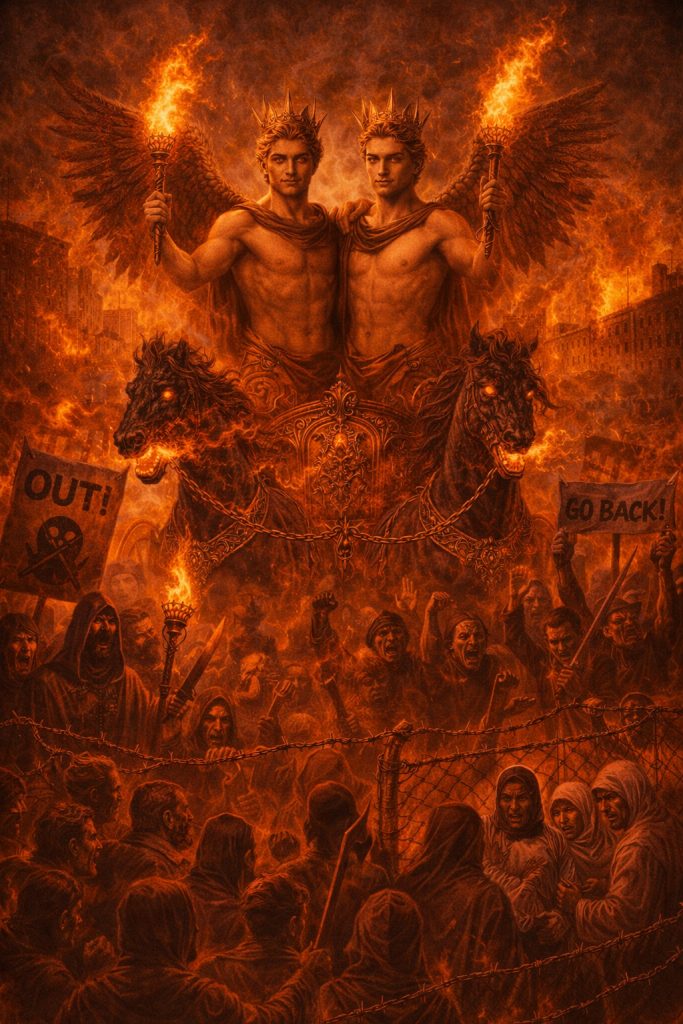

Such unity is always built around boundaries, not around creativity, construction, or common sense. And it is precisely that boundary that becomes the chief value and the object of faith, making the world monochrome and sharply dividing it into “our own” and the foreign, those “with us” and those “against us.” Belial so intensifies the sense of separateness and “exclusivity” that the external threat itself becomes the only glue holding the collective together; therefore wars, conflicts, pogroms, persecutions, and moral panics become virtually the only sustaining context for such societies.

It is clear that immature societies often hold together precisely through opposition, and Belial incites conflicts in order to stoke the feeling of separateness and “chosenness,” so that this conviction functions as an emotional organizing principle: the chaos of the world, anxiety about the future, fear of our own weakness and inner emptiness are vented by demonizing the “other.”

Conversely, the false unity inspired by Belial is experienced as a comforting sense of belonging, where the “other” is blamed for everything that is bad, and therefore such a collective needs hatred simply to avoid falling apart. It must regularly confirm that the “enemy” exists, that the enemy is always cunning and malevolent, that the boundary is real, and that the outside is inherently dangerous. People thus grow close merely because they were taught to share hatred for the same target. Attraction is reversed: the force that normally unites degenerates into a mechanism of division; unity becomes a form of alienation, albeit a collective one.

It is not hard to see that psychologically repulsion is always easier than love: true unity requires inner maturity, the ability to endure difference, the skill of seeing reality and value in another even amid disagreement. Anger provides the illusion of action instead of confronting pain, shame, loneliness, and weakness. So a collectivity sustained by Belial always needs arousal, a shared adrenaline rush; its cementing “sense of an enemy” must be maintained by constant confirmation of that enemy’s malice and foreignness. Hence the leaders of such collectivities are not stingy with lies and provocations, stoking the fear and hatred that bind people. Then, instead of inner agreement, what unites is a shared spasm, a common defensive reflex, a collective ban on doubt.

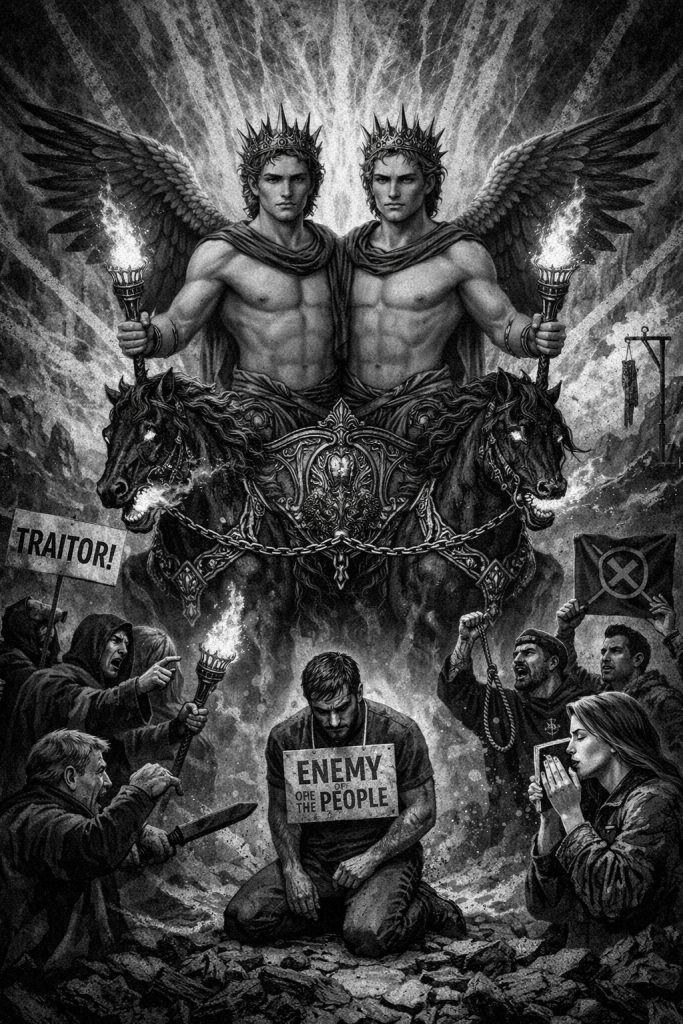

A sense of “we” founded on repulsion inevitably devalues the individual. In it a person matters only insofar as he hates rightly. Hence the need for constant displays of loyalty, the hunt for “traitors,” ostentatious rituals of public righteousness. Such a collectivity constantly and jealously tests the capacity to reject the “foreign.” Any attempt at compassion for outsiders, any respect for another’s value, is perceived as a threat to the group’s wholeness and therefore denounced as almost the worst of all “sins.”

At the same time, the image of the “other” in collectivities sustained by the King of Hatred is needed not only as a source of unity and relief of tension; it also serves as a container for the group’s own shadow. The collective projects onto it everything it refuses to acknowledge in itself: greed, cowardice, envy, cruelty, inner emptiness. It is obvious that after such projection a feeling of purity arises: “we have none of that; it is all theirs.” From this comes the sweet mystical belief that “we stand on the side of the light,” even though the very mode of “unity” clearly indicates the opposite direction.

It is easy to understand that such false unity is always destructive and unproductive; it cannot inspire creativity and does not strengthen individuals. Real growth, meanwhile, always requires inner freedom and the capacity for dialogue; a collectivity built on hatred, however, relies on monologue — on uniformity, shared pain, and shared rage. At its base is always a cold emptiness that must be filled again and again with externally provoked fear and xenophobia.

Such unity creates nothing; it persists only so long as there is a target of revulsion, as long as there is an external “enemy,” a “scapegoat.” It can mobilize, raise a clamor, provoke a surge of energy, but that energy is not creative or generative — only convulsive. It has no future because it has no positive internal source; it needs fresh confirmation each time through new doses of repulsion. Therefore it does not nurture people but wears them out, cultivating suspicion and irritation.

Sooner or later this hatred inevitably gets out of control. It requires a constant “fresh dose” and begins searching for the “other” within its own ranks. Any aggression that becomes the basis of identity needs continual feeding and release; it develops its own inertia and then easily spills over onto those nearest — family, neighbors, colleagues, random passersby. Those shaped by Belial’s matrix start to live in constant readiness to attack, and the world around them gradually becomes what they imagine — hostile, cold, dangerous. Thus Belial turns people into obstacles to each other, and “unity” into a mechanism of self-poisoning, where collective hatred inevitably returns to those who produced it and destroys them from within, even if outwardly they continue for a long time to call themselves “cohesive.”

When “national identity” is built on the idea that “we are those who were enslaved, and therefore are fighters against the colonizers,” an imagined, idealized “free past” is presented as the sole measure of righteousness, and the future is reduced to an endless pursuit of that righteousness. Such a collectivity requires a permanent adversary; otherwise its self-description collapses.

Memory ceases to be a root that nourishes and sustains growth, and with it the ability to continue as a people is undermined: the inner core of tradition is denied, cultural continuity is repudiated, the acceptance of complex truths is condemned, and only hysteria and the need constantly to affirm existence by fueling conflict are approved.

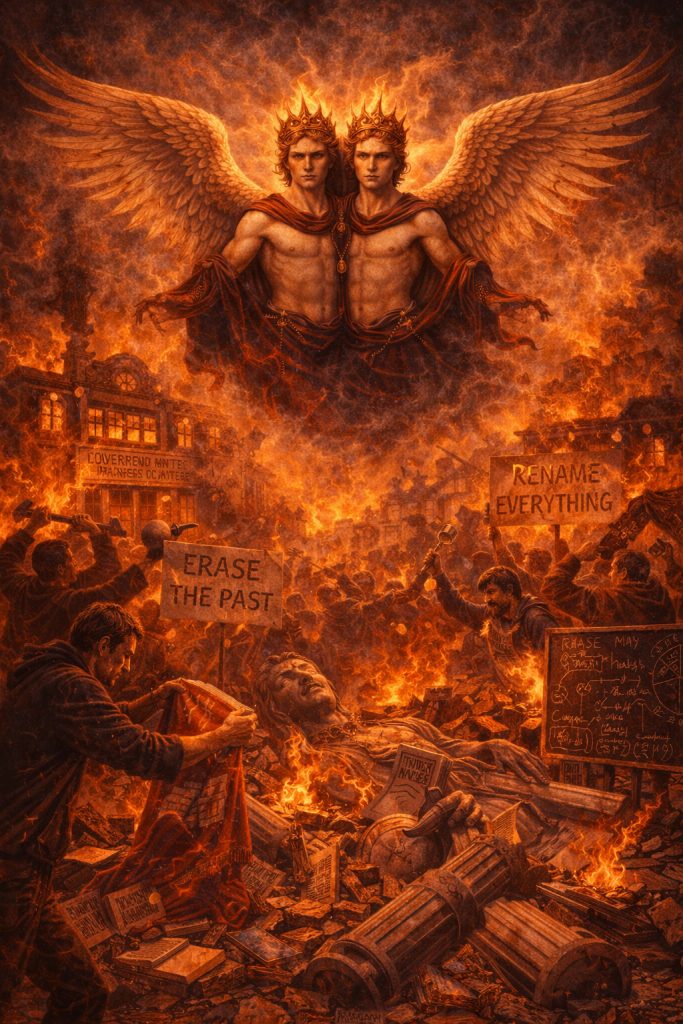

In this scenario the past is described as an unbroken wound, and identity is built around that wound as the only proof of authenticity. A person or community sustains its sense of righteousness through continuous tension and accusation, when the past is not to be understood but to be destroyed; memory is not to be examined but to be forbidden; heritage is not to be transformed but is declared toxic.

This position feels liberating because it grants a sense of moral superiority and creates a simplified picture of the world. Yet it destroys where reinforcement was needed: the collectivity loses the ability to create, because creation always implies connection, recognition of the other’s value, and weaving one’s own into a broader context. Under Belial’s influence, respect for other cultures is perceived as betrayal, and the search for points of contact is seen as weakness.

Then the past ceases to be the soil from which the future grows and becomes a field of exile: calls arise to erase traces of the “other” in order to feel “ourselves.” Tearing down monuments, burning books, renaming streets and cities are presented as a kind of “purification ritual” in which the act matters more than the result: it feeds the feeling of unity, directs aggression in one direction, and cultivates the idea that “we exist so long as we fight what came before us.” Such an identity is deeply dependent: it needs a permanent enemy. Yesterday the enemy lived in the past as an “imperialist” or “colonizer”; today he is found in libraries, toponymy, school curricula, building ornamentation. Tomorrow the enemy will inevitably be found inside the community itself: those “not righteous enough,” “doubters,” those who “remember differently.” Aggression by its nature seeks continuation and easily spreads all around, so “cleansing memory” too often becomes an epidemic of witch hunts.

The main harm of this pathology is the destruction of the very ability to inherit and rework. When the past is declared purely poisonous, one’s own development is undermined along with it: language, educational forms, the peculiarities of cultural formation, art, and science. Such a collectivity knows only how to destroy and rename; it loses the capacity to build: to found schools, foster science, develop the economy, establish institutions, produce a culture that is truly useful to children rather than to a traumatized and hysterical crowd.

With this attitude a constructive future is impossible by definition, because a productive future requires a positive form — an image of what is being created, the purpose for which unity is built, what is taught, what is preserved, and what is relied upon. Belial offers only a negative form — an image of what must be rejected, destroyed, and stigmatized. Certainly this negative form can be powerful; it brings people together quickly and is almost always emotionally compelling, but it corrodes its bearers: it turns memory into a battleground, culture into an instrument of reprisal, society into a herd that lives solely on arousal.

But the formation of an individual or a people is like the growth of a tree: it grows toward the future while feeding on its roots. One can acknowledge that there is rot in the roots, part of the soil is poisoned, some old branches have become dangerous. Cleansing and transplanting are possible, grafting is possible, new crown forms are possible. However, the decision to “cut out the roots and rid oneself of pain” paralyzes the very possibility of growth: by removing the offender one erases one’s own biography, and by the violence one erases language, skills, disciplines, and culture — the very things through which a collectivity initially formed.

Therefore the struggle against the past under the guise of liberation usually leads to cultural impotence, and memory turns into an endless field of purifying bonfires where every step aside is declared treason and every complexity is used to justify the oppressor.

So the principal risk of the “decolonization complex” lies in replacing the future with a war on memory. In that war it is easy to defeat a monument, change a street name, or alter a reading list, but it is all too easy to lose one’s own ability to mature, because the future can only be built where the past has been worked through and inscribed. One thing is reassessment and an honest conversation about the crimes of the past; another is the cult of cancellation as a way of feeling united. In the first case the past remains material for learning and growth; in the second it becomes a target, and the target gradually becomes the sole basis of identity. And where the basis is such, it always leads to increasing destruction, simply because hatred does not know how to stop.

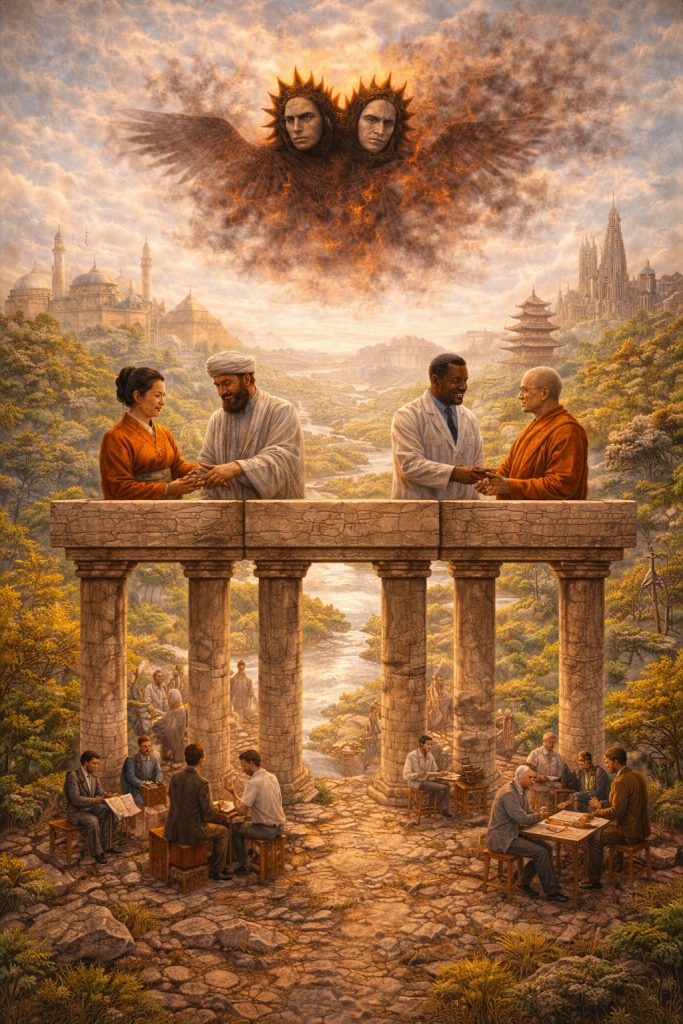

The antidote to Belial’s influence must, of course, be respect for other people’s values, love and compassion, and a sober view of society that studies history and recognizes the importance of interethnic, intercultural, and interreligious connections. It is important to restore the past to its true function — to be a foundation and a school where mistakes are distinguished but strength is inherited.

Societal bonds should be built around positive meanings and creative deeds, around recognition of another’s value, around a shared sense of humanity. Belial keeps society in a state of heightened tension; he needs the image of the “other” so the group feels alive.

Where a person learns to see the value of the other, the need for humiliation disappears, and with it the fuel for “unity” through revulsion. It is necessary to seek points of contact as the basis of connection. If a collective’s lexicon and life revolve around discussing “what we build,” “what long-term meaning we create,” and “where we can cooperate,” then the community ceases to require constant nourishment from hatred. Such a collectivity becomes productive: joint work appears, mutual enrichment, exchange of competencies, a shared future. This is the direct opposite of a herd that “warms itself” on threats and constant internal loyalty tests.

It is necessary to maintain the capacity for sober discernment, to remember the cost of dehumanization, to calculate consequences beyond a single emotional surge, and to see in the “enemy” first and foremost a human being, not a demonized figure.

A society under Belial’s sway feeds on myths and fantasies of its own exceptionality. The antidote must therefore be an understanding of interconnections: how cultures, peoples, schools, and traditions have long influenced one another, and how many great values were born from exchange and proximity. A proper study of history and of the importance of intercultural and interreligious ties restores sobriety and reduces susceptibility to mass suggestion.

Of course personal work is no less important; without it any “practice of loving the other” will remain a mere slogan. Belial exploits a person’s shadow side — suppressed fear, the desire to be right, the craving for simplicity, and the need for a strong group as a substitute for inner support. Therefore it is very important to learn to recognize in oneself the moment when irritation becomes pleasurable and when the need to prove one is right through humiliating another appears. In that instant the outcome is decided: either the energy of repulsion turns into a destructive force, or the person regains the freedom of choice and refuses to hand it over to the demonic vortex.

Thus the resistance to Belial’s “false unity” must rest on three pillars: respect for the value of the other, the search for points of contact as the basis of connection, and the restoration of inner wholeness through sober and deep reflection. When these pillars become strong enough, a society no longer needs hatred as glue, and Belial loses precisely the channel of power that today seems almost insurmountable.

Thank you!

It’s interesting that this has happened a few times already—I’m thinking about something, and then an article comes out here answering my question…

The article is deep and very interesting.

It has several layers.

Everything described here is also applicable to my own life.