Planets as Spheromata

When people think of the physical cosmos, they typically picture a boundless, “homogeneous” expanse in which galaxies, stars, and planetary systems “float”.

From a magical perspective, however, this image is overly simplistic. In traditional thought space is not an independently existing entity but a measure of separation between different “abodes of consciousness” (and time is only a conventional measure of the actualization of potentials). Put differently: while time gauges how far apart two states of the same system are, space gauges the degree of difference between distinct systems. Thus physical space is only one projection—useful for bodies and calculations—whereas the real “distance” between worlds is determined by the mismatch of their internal laws and stability profiles.

Viewed this way, the notion of distance can be examined on several levels. On the physical level it appears as spatial extent and the cost of movement. On the causal level it is the degree to which laws coincide: the less they coincide, the more effort is required to translate one order of events into another. On the semantic level it is the amount of information that must be processed to “transition” from a description of one system to an account of another.

In this sense any physical cosmos is a “particular” slice of the totipotent hyperspace of the interworld, and thus constitutes a collection of “habitable islands” embedded in a fabric of instability.

Accordingly, planets (and other bodies) in this cosmology function not as merely one among many material formations, but as multilayered, multi-level systems—the very “islands of stability” immersed in “space,” which acts to separate and insulate them from one another.

Thus, from this traditional viewpoint, interplanetary and interstellar space is not an “ocean” that “connects” discrete bodies, but a medium that keeps those bodies isolated from each other.

Celestial bodies are not merely “clumps of matter”; they are complex, multilayered systems encompassing a vast range of both “vertical” and “horizontal” manifestations.

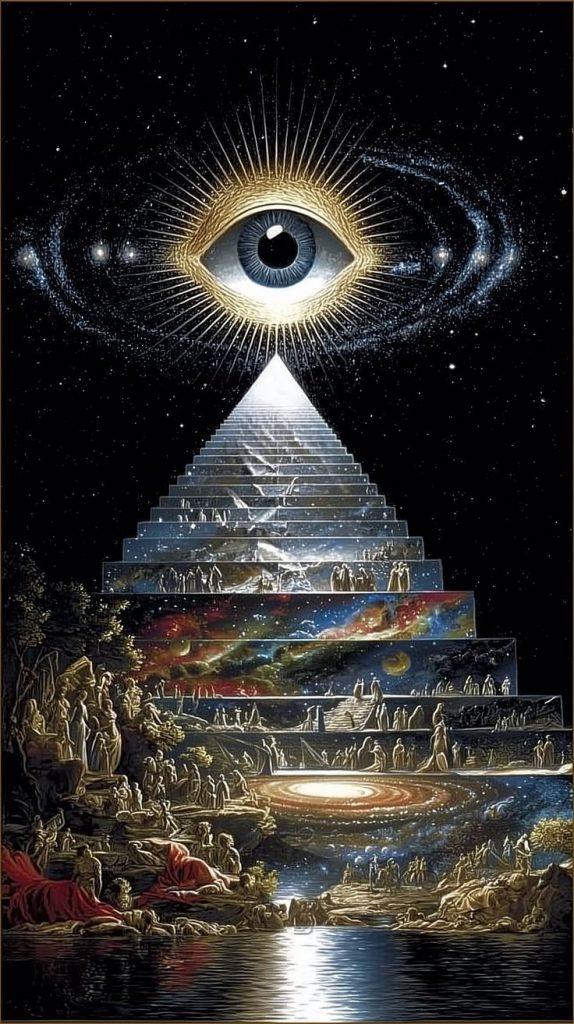

This is the crucial difference between Traditional and profane cosmologies: the former are “geocentric“—not out of ignorance, but because they adopt a broader perspective. For the Hermeticist the world is, above all, a “universe inward,” whereas for the uninitiated it is a “universe outward.”

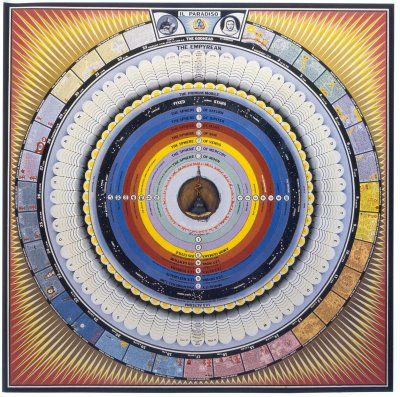

The Pythagoreans, two and a half millennia ago, were clear about the order of celestial motion: for them “geocentricity” marked a point of reference rather than a statement of physical causation. They distinguished two concepts. The first—”kosmos” (κόσμος)—is the space in which planets, the Sun, and the Moon move. Its role is to establish relations among different forms of motion: the kosmos is the domain of harmonious movement where the “music of the spheres” arises. In this language planets function more like “notes” and “chords” than as bodies that attract or repel one another. The second concept—”spheromata” (σφαιρώματα)—refers to nested spaces: spheres organizing different levels of reality around a single center (ὀμφαλός). This center acts as the principle of the system’s self-identity, the shared logos that binds all levels and lines into a single structure—a unified set of interrelated permissible transformations.

A similar model exists in the East, where such nested worlds were called “brahmakosha” (“the shells of Brahma”), and later theosophy described it as the “planetary chain“. In the last century the visionary Daniil Andreyev synthesized these ideas in the image of the “bramfatura” (“the structure of Brahma”—from “Brahma,” the organizing god of the universe in Hinduism; the name relates to “growth, increase, rise,” and “facture” connotes making or structure). A comparable image is offered by the concept of the “World Tree“, notably Yggdrasil. Mythological toponyms thus function as descriptions of the modes of being of a given spheromata: they indicate the kind of guide required, the degree of stability necessary, and the key needed for transition.

All these concepts indicate that the planet perceived by “ordinary sight” (σῶμα) is only one layer within a far more complex system: vertically it is a stack of hierarchically distinct worlds connected by energy flows; horizontally it comprises the totality of possible states (timelines) or developmental pathways of each world.

From this perspective, popular notions of “traveling between the stars” in physical vehicles seem unlikely. Interactions between different levels and layers within a single spheromata, however, are far more significant and practicable. Consequently, most reported contacts with “extraterrestrial beings” are likely encounters with inhabitants of other hierarchical worlds (often igvas), with “people” from other times or variants, or with fae.

The same holds for “journeys” through the spheromata: by “ascending” consciousness to more “subtle” conduits, perception can shift to hierarchically different worlds—one may “visit” Asgard or Vanaheim—without any physical movement; only the viewpoint, the “slice of reality,” changes. By means of a shift, consciousness can traverse different variants or timelines and may arrive in entirely unfamiliar worlds if those branches split long ago and followed divergent developments. A third possibility is that consciousness exits a given mode of perception and finds itself in the position of the Interval, with its own geography and inhabitants. Each of these aspects has its own temporal and spatial extent, which need not coincide. For example, at the level of Vanaheim the distance between “Earth” and “Mars” can be much closer than at the level of Midgard, and once the “earthly” and “martian” Vans interacted closely.

Ultimately, a planet can be seen as a center that assembles reality: the visible sphere is but one level of a broader system. This implies that humanity’s true “cosmicity” is measured not by the maximum distance it can travel through physical space or by the number of coordinates it has mastered, but by the quality of its access to the levels already present within its planet’s bramfatura.

Thus, “journeying” through the spheromata becomes a measure of consciousness’s maturity—its capacity to move through its own levels and spheres and through the “slices” of the complex external multi‑world available to it.

Accordingly, the concept of the spheromata restores traditional “geocentrism” to its original sense. The center is the logos of the structure: it does not indicate a body’s mechanical position but determines each element’s participation in the deep organization of the complex world. A person lives in the “universe inward” even when unaware of it; fate unfolds simultaneously on multiple levels, and every decision resonates not only in physical events but in the histories of energy, information, and choice. This perspective encourages a broader understanding of the world and one’s place in it, and a more responsible attitude toward actions, impulses, and thoughts.

Are spheroids and bramfatures the same as the cosmic golden egg? According to one myth, God (I think it’s the Archons) carves out voids in the darkness for these eggs? And how can one end up in another world, and which system should be chosen?

The Spheromata is like a “mini-universe,” largely a closed system that operates according to its own laws and cycles. Typically, consciousness reincarnates from life to life within a single Spheromata, and this applies to both humans and gods. It’s clear that the Archons, as principles, are universal beings; however, at the level of the Spheromata, they have their own manifestations, just like other higher hierarchies, such as Archangels.