Reckoning and Creation

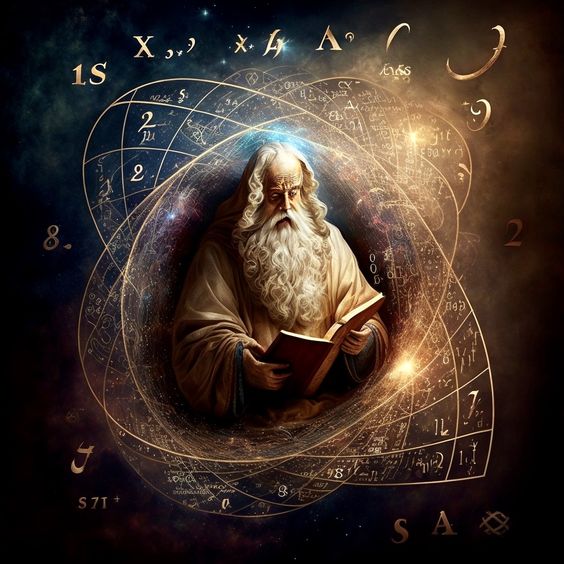

When the Kabbalistic tradition calls the “skeleton” of reality the “sefirot” (a word, one of the meanings of which is “reckoning,” “digit”), and Pythagoras says that “number is God,” they mean one and the same thing — the matrix, or eidetic, primal basis of being.

As we have already discussed, the myth we are considering says that reality is a product of description, interpretation; it exists only conditionally, and arises only upon contact of the describing (calculating) mind with the potential environment.

At the same time, since mind and medium are not separate entities but different properties, modes of one integral Great Spirit, the process of awareness — or, equivalently, creation, the becoming of reality — is a continuum that can be considered on different levels.

“Pure mind” — monads — is rather an abstract possibility of awareness, just as a “pure object” — “energies” — is only a possibility of being known; and their interaction itself, realization, cognition, is expressed in its maximal, perfect form as logos (meaning, awareness in the proper sense of the word); on the cognizable, processual level — as an “idea,” eidos (or, in modern scientific language — an equation); and at the level of interactions, concretely measurable properties — as a “measure” (Me, midot, matrix of perception).

At the same time, the perception of logoi is a function of “vedenie,” while eidoses and measures can be perceived by “ordinary” manifestations of mind.

Moreover, when a mathematician derives a particular equation, and a physicist discovers that this equation accurately describes some aspect or process of reality — they are dealing with eidoses and Me respectively. In other words, the “derivation” of an equation, for example the Theory of Relativity, is precisely a journey of mind through the domain of eidoses, and the mathematical solving of equations is quite equivalent to Pythagorean or Platonic insight into ideal reality.

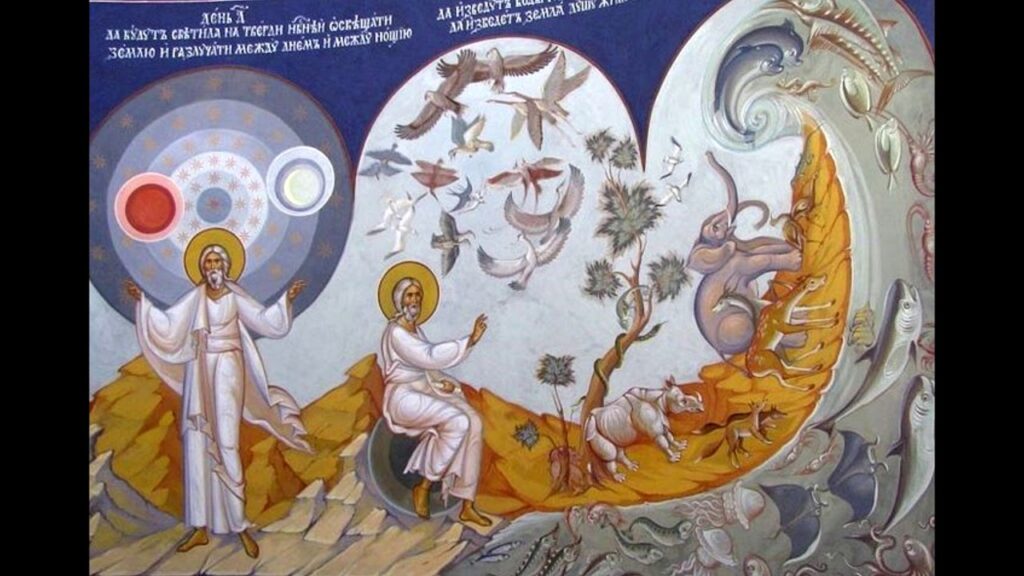

It is clear that eidos (and even more so Me) can be “discovered,” realized in different ways, among which the numerical, mathematical one is not the only one. Sacred drawings and symbolic systems, sacred music and religious hymns are also ways of direct access by the mind into eidetic reality. That is, the same knowledge that, for example, a mathematician gains by “traveling” through their calculations and reckonings, a musician can gain through the perception of harmonies, and an artist — through abstract images and figures.

Accordingly, the world of ideas, the foundation of reality, is simultaneously the world of mathematics, the world of abstract equations and reckonings, and the world of images, sensations, attractions. That is, one can equally effectively “calculate” and “feel” the world, and some particularly capable beings are able to combine these two ways and “see” equations without “deriving” them. Apparently, it was precisely such a talent that, for example, the famous Srinivasa Ramanujan possessed; he “saw” equations and theorems without their “derivation” or proof.

Accordingly, the three main ways of wisdom — cognition, sensation, and insight — are simply different approaches to one and the same foundation of reality. A scientist, an artist, and a mystic can touch one and the same eidos, expressing it in ways accessible to them.

This was well understood by the adepts of the Pythagorean and Platonic initiatory traditions, who sought to unite different approaches to mutually verify and obtain the most complete and multifaceted representation of the foundation of reality. Moreover, with a sufficiently serious (and transcendent, surpassing) approach, especially talented representatives of such schools managed to gain insight into the reality of logoi as well, seeing not only the “skeleton” of reality but also its “guiding grid,” the ground of being.

Accordingly, the task of the Wayfarer, striving for living life as fully as possible and, consequently, for the fullest possible description of their reality, turns out to be the expansion of their view of the world perceived by them (and simultaneously created by them), considering as many perspectives and approaches as possible.

Yes, Rudolf Steiner also speaks of expanding ‘points of view’ expressed in 12 worldviews corresponding to the 12 zodiac signs. He identified – spiritualism, pneumaticism, psychism, idealism, rationalism, mathematicism, materialism, sensationalism, phenomenalism, realism, dynamism, monadism, refracted, in turn, into seven mental states (gnosis, logicism, voluntarism, empiricism, mysticism, transcendentalism, occultism), and further through three ‘tonalities’ (theism, intuitivism, naturalism – analogous to the triad of Spirit, Soul, Body). Many points of view, and the truth lies in the middle.