Atlantis Before the Atlanteans

Legends of Atlantis — a fairy-tale land of sages and magical technologies — have always stirred people’s imaginations. For some, Atlantis recalled a lost Golden Age; for others, it was evidence of ancient victories and primordial wisdom that was not divine but “purely human”; and for others, it was a reminder of the dangers of the predominance of technology over spirituality.

In all legends and traditions, Atlantis (Ta-meru) is first and foremost the “land of Masters,” the first manifestation in the world of formed and forming forces, the first victory and the first failure of creative efforts.

According to tradition, this country arose long before humans — as an outpost of alvs and sids, where, back in the Age of the Tuatha Dé Danann, svartalvs settled and established their great workshops.

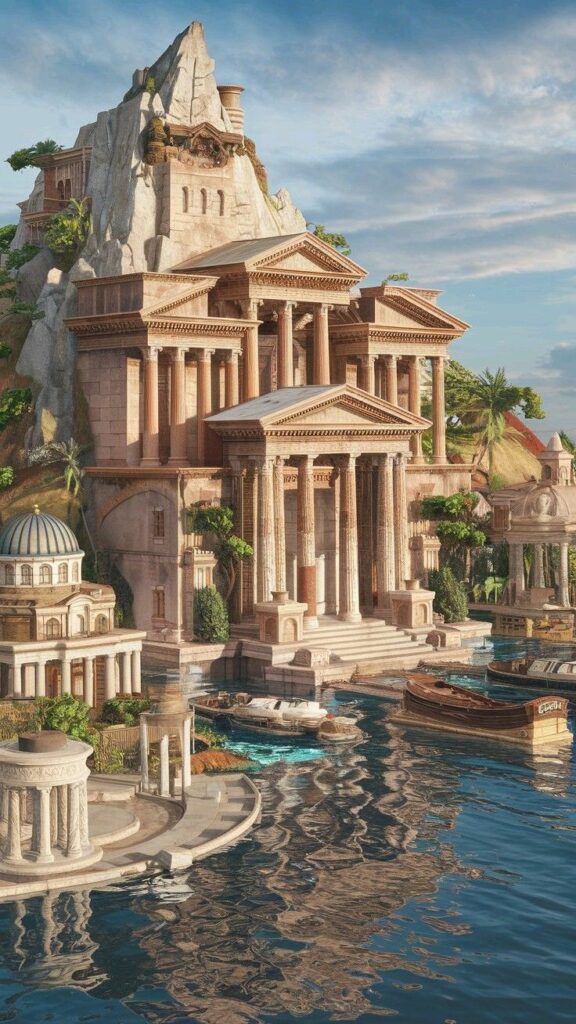

It was a vast archipelago that grew as a result of three geological events occurring simultaneously: the breakup of Pangaea and the rift between Laurasia and Gondwana; a series of partial rifts in the crust that left uplifted banks and plateaus above sea level; and early surges of basaltic magmatism along the future Azores–Gibraltar transform zone.

About 150 million years ago, these processes created an arc of islands: from the future site of Gibraltar, to the west and northwest, a ridge of fault terraces, shelf plateaus, and young volcanoes formed, where the stone was still “warm” and pliable to shaping.

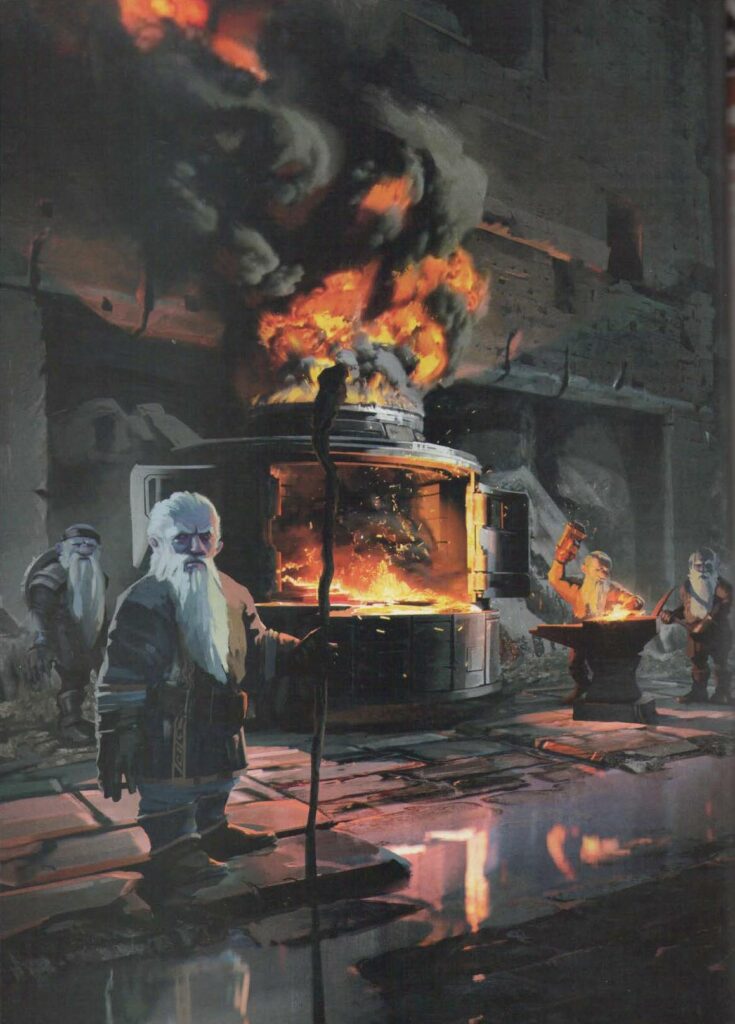

It was on such islands that the alvs and sids built their main castles, and the svartalvs — masters of form, stone, and metal — built strongholds in the Middle World, where they processed ores, using geothermal heat from the depths, built crystalline structures not yet fully hardened, created new kinds of matter, and “tamed” energy. Thus the “Land of Masters” was born.

Here, from the beginning, collaborative work prevailed. Alvs maintained order and structure; sids connected the Flows and forms, bringing channels to their castles from the four Elemental Cities — Falias, Murias, Finias, and Gorias; the svartalvs provided forging, transformation, engineering — from processing ore-bearing rock to fine-tuning passages between the layers of worlds and the Interworld.

Its position at the Gates of Vanaheim — where much later Gibraltar would arise — made the archipelago a natural gateway for the Vanir: in waves, during the Jurassic–Cretaceous periods, elementals came here, guiding the coevolution of flowering plants and their pollinators, creating the first placental mammals, laying out fish routes along ocean currents. Thus Atlantis was at once a school and a workshop where work on form was done for the sake of perfecting life itself, preparing biological forms for an ever fuller entry of mind into matter.

The island landscapes were shaped along faults of the earth’s crust; where cracks exposed “green stones” — serpentinites and similar rocks — the svartalvs built their workshop halls, and where young basalt formations still radiated heat, they built forges fed by interior heat; on banks where the stone is “charged” by the energy of the tides there were “listening” platforms — energy-harvesting platforms even from weak sea currents.

The craft of the dvergs actively used the acoustics of matter: stone, water, fire, and air were bound together in techniques where tools were never separated from the primaelement, and the working process originated in the Master’s mind.

The svartalvs knew the price of time: they understood that haste is the enemy of crystal, but also that stagnation is the danger of the ossification of fluid form.

Over time, the “Land of Masters” expressed ideas of balance through oaths and agreements: a gift must be reciprocated, help only in exchange for real reciprocity. Any work here required “payment”: for every passage laid, for every artifact forged, one had to return to the Flow exactly enough so that it would not “run shallow,” and not a drop less, not a drop more.

Memories of this land have been preserved in different traditions, as the memory of an island forge where fire meets the sea. In the northern tradition, it is Niðavellir, the halls of the Dark alvs/dvergs, where the tools of the gods were forged and where agreements were valued more than gold. In the Celtic tradition, these are tales of the three god-Masters (Goibniu, Luchtaine, and Creidhne). Among the Hellenes, traditions have survived about the Cabiri of Samothrace and Elis, the Telchines of Rhodes, the forge of Hephaestus under Etna, and the Cyclopean caves. In Semitic-Hittite myths there are traditions about Kothar-wa-Khasis, the divine builder whose workshop seems to stand “on an island,” at the water’s edge. In the Indian tradition, the master Vishvakarman, engineer and architect of worlds, and Maya-danava, the dark Master of “illusory cities,” are described. In Germanic sagas they speak of the Nibelungs, smiths under the mountain, whose gold becomes a curse if an oath is broken.

All these traditions mention a certain duality of mastery that would determine the future fate of Atlantis: a combination of the craft of transformation, service to life — and coercive technocracy.

As long as Atlantis remained the workshop of the alvs and sids, the alliance of spirit, matter, and technology was pure.

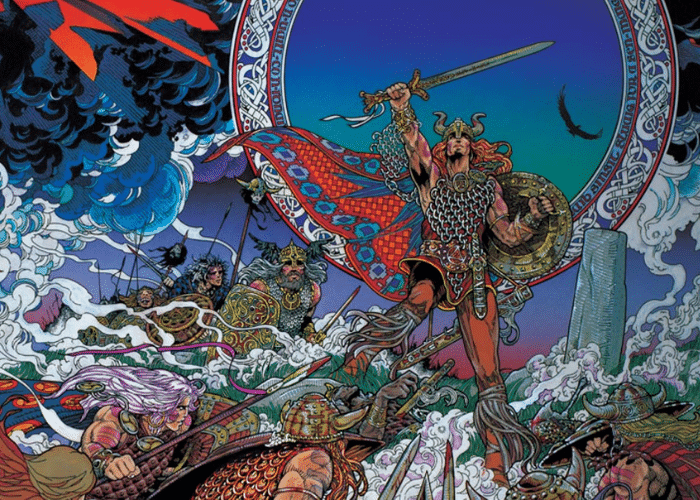

However, the world was changing: first the Fomors manifested again on Gondwana, and then spread northward. A war flared up — “The Second Battle of Mag Tuired,” which forced the forges to become defensive: the svartalvs were already forging in them not only bridges and ritual knives of orichalcum, but also shields for the Castles.

In this war, the svartalvs played a role no less important than the lessalvs, the Aesir, or the Vanir, although chronicles mention them less often. From ancient times they taught the peoples of fae to give form to matter, to give forms stability and the capacity to contain energy and spirit. And therefore, in the Second Battle, their influence manifested through their grateful students: kobolds, guardians of ore veins, supplied the army with weapons that did not melt under Fomor fire. Kobolds, cunning and hardy, led assault units armed with dverg blades and spears. Forgs, smithing peoples, fanned the fire of creation opposed to the demonic flame of Balor, and forged shields capable of reflecting the destructive light of his eye. Leprechauns, Masters who had adopted from the svartalvs the secrets of laying fate upon a thing, created artifacts that bent probabilities and led allies out from under deadly blows.

When the Fomors began to burn the bodies of the sids with their fire, pushing them into bodiless existence, it was the svartalvs who created temporary stone-and-metal vessels into which spirits could enter, keeping a connection with the dense world — the first experience of “prosthetics” and of creating “external information stores.”

After the fall of the “Eye of Balor” and the mass extinction at the end of the Mesozoic era, the world of fae entered a long Golden Age, in which mammals diversified and spread, birds filled the sky, flowering plants expanded and “settled in” with insects, and Atlantis and Shambhala finally formed as two outposts of creative forces.

However, then humans appeared, and at first the svartalvs were openly friendly with these new beings: they taught them to build cromlechs and arches without damaging the stones, to cast metals without destroying forests, to lay tunnels so that rivers would not run dry. The chronicles of Kaihir mention precisely such forms of cooperation, and bridge-builders who knew two languages — human and fae — knew how to “remove” the tensions of lands without injuring them.

Humans came to the Ta-meru archipelago approximately 70 thousand years ago, when shelf plains stretched from the coasts of North Africa to Western Europe. At first these were only rare voyages of hunters and seafarers, scouting paths to the “islands of Masters.” The first contacts were limited: humans listened to the wisdom of the Magical peoples, gradually and as best they could (and as their minds allowed) adopted their techniques; the svartalvs, in turn, studied human physical and mental traits.

However, this friendship proved more fragile than it seemed. Humans, developing under the influence of predatory forces, wanted to accelerate the transformation of matter and control over it. They needed results “by a set deadline”; they were not afraid of violence against form.

Where growing flows of energy into the Interval were at stake, the Archons stoked tendencies in humans that served them: a tendency to colonize lands, toward consumerism, to violence against the world’s flows and even against their own feelings. This “coldness in the heart” helped humans do what neither the fae, nor even more so the alvs, could allow themselves without betraying their very essence.

That was when the “Battle of Sliab Mis” broke out — the first open clash of humans with the fae (and the svartalvs), which led to a “change of power” in Atlantis and to humans taking the dominant position in it.

Moreover, humans quickly learned: a threat to sacred places is the strongest lever of power over the ancient peoples. They took hostage not only the Masters and their families, but also places, with conditions like: “you reveal the secret — we will leave the key spring alone; you refuse — we will choke it off.”

And already about 20 thousand years ago, on the islands of Ta-meru, the first “quarters” appeared, and in effect, ghettos for Masters — underground labyrinths into which the svartalvs were driven as into craft casemates, replacing agreements with coercion. Technologies became increasingly harmful to nature and increasingly consumerist.

Thus an Atlantean power was born — a human power that grew atop and outside the workshops of the Magical peoples.

At the culmination of this degradation, the Atlanteans tried to open a permanent portal into Alfheim, and the druid Kaihir, the last of the intermediary bridge-builders, sacrificed his life to close the breach. Atlantis sank, causing a Flood, and part of its population dispersed across different continents and countries.

After the Flood, in the Holocene epoch, the world for a long time still responded to the fall of Atlantis with a “second deluge”: the last plains sank, shoals sank into the depths, and the fae curtailed their manifest presence in the world, gradually going “under the hills,” into Castles, into the spaces of the Interworld. Humans, meanwhile, strengthened shores, built cities and new harbors, carrying over land and sea two inheritances at once: technology and coercion. This is precisely the main outcome of Atlantean history: former “students” became overseers because they learned, through deceit and violence, to “live on credit” from the world without repaying it.

After the catastrophe that swallowed Atlantis about 12 thousand years ago, the Atlanteans settled in new lands, leaving a deep mark on human history. They dispersed across nearby territories: some moved into North Africa, some — to the Eastern Mediterranean, carrying with them the memory of their ancestral homeland and part of its knowledge — the skills to build, cultivate the land, and organize communities; and the least “corrupted” part of the Atlanteans founded the first cities of future Egypt. It is no accident that many Egyptian legends point to the “Western Island,” the sunken land of sages, as the source of their culture.

And even today, on marine bathymetric maps, one can make out the former geography of Atlantis: banks to the west of Gibraltar, elevations extending toward the Azores, chains of underwater mountains.

The story of the Atlanteans contains a double legacy. On the one hand, they brought into the world a creative power: the skills to build temples and cities, to order the chaos of nature, to raise culture to new heights. But on the other hand, it was they who spread across the world the shadow of pride, lust for power, and cruelty. These two poles have accompanied all humanity ever since. The Atlanteans gave the world the first hearths of civilization, but together with them — the seed of an inner split: between creation and destruction, between service to higher aims and the subjugation of the world and beings within it to one’s personal gain.

Thank you. The story of Atlantis remains relevant.