Ogham and Celtic Interlaces

As we discussed earlier, alongside the Runic Tradition, a vector description of the flow of Force was also developed by the ancient Celts and encoded in the Oghamic alphabet.

In the same way as the vortex and vector descriptions of the process focus attention on the doer and the action, both the vortex and the vector can be considered “externally” and “internally”. At the same time, if the Runic system is focused on the vector manifestations of the creative will, then Ogham is focused on the directed flow of the power of natural, immanent processes. In other words, if the Runes describe vectors of force from the practitioner’s perspective (“natura naturans”), then Ogham describes them “from within” the very “fabric” of the process (“natura naturata”), thus constituting the most in-depth point of view on the flow of Force (while the most “external” view is formed in the vortex description).

One might say that Nominative Magic answers the question: “Who acts?”, Sigil Magic: “What does he do?”, Runic Magic: “What is his will?”, and Knot Magic: “What does he achieve?”. In other words, if we are focused on the agent, we seek his Name; if on the expression of his desire, we build a sigil; if what matters to us is the result of the manifestation of will, we carve a bind-rune or a galdrastaf; and if we want to trace the entire course of realization, then we weave knots.

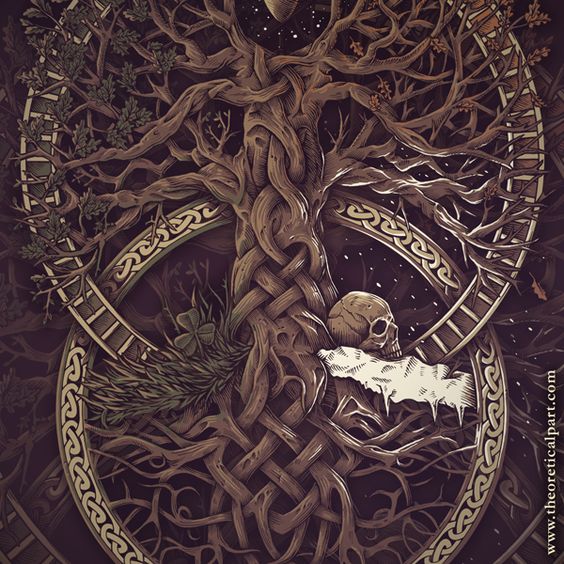

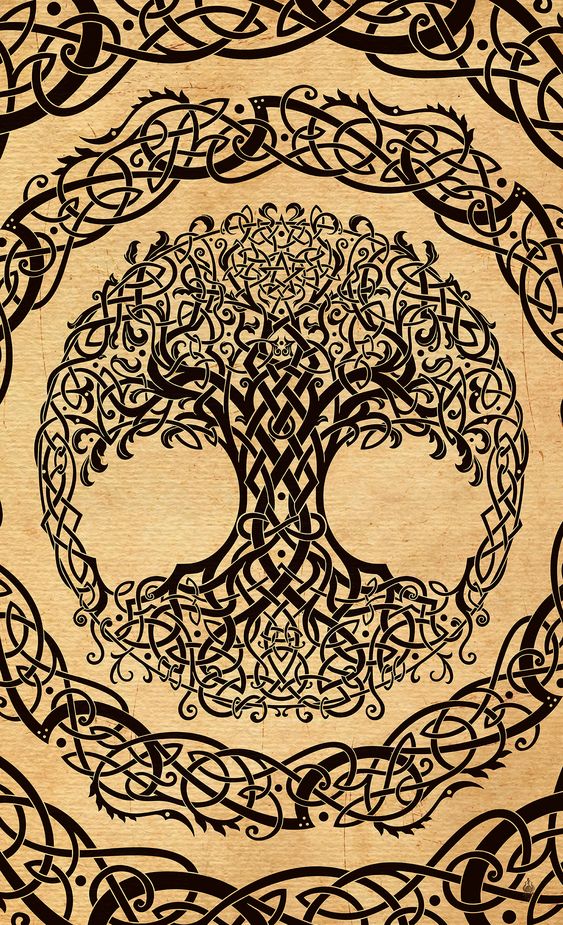

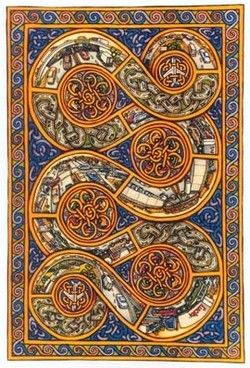

And just as Runic vectors, interweaving, give birth to galdrastafs and aegishjalmurs, Oghamic currents flow into the whimsical knots of Celtic ornament.

Unlike the “arrows” and “spears” of the Runes, clearly flying toward their goal, Oghamic vectors are like the gentle flow of sap through branches, shrubs, and lianas, always rooted in the earth and striving toward the sun, yet seeking the optimal path, which may turn out to be quite winding. Therefore, the interaction of such currents often proves whimsical and ornate, like the interlacing of tree canopies in a dense forest.

Intricate interwoven patterns, known as braids in British usage, first appeared in the Late Roman period in various parts of Europe — on stones, walls, mosaic floors, and other surfaces. Spirals, step patterns, and knots are the dominant motifs in Celtic art prior to Christian influence (until approximately the year 450). Such drawings were reflected in early Christian manuscripts and works of art, with the addition of images from life — animals, plants, and people.

Although the style of knot ornament itself first appeared in Italy (the same place where the Etruscan “progenitors” of the Runes emerged), it reached its greatest flourishing in Ireland, having been nourished by the Oghamic, “plant-like” spirit. This style is most often associated with Celtic lands, though it was also widely practiced in England and spread to continental Europe thanks to Irish and Northumbrian monastic activity on the continent.

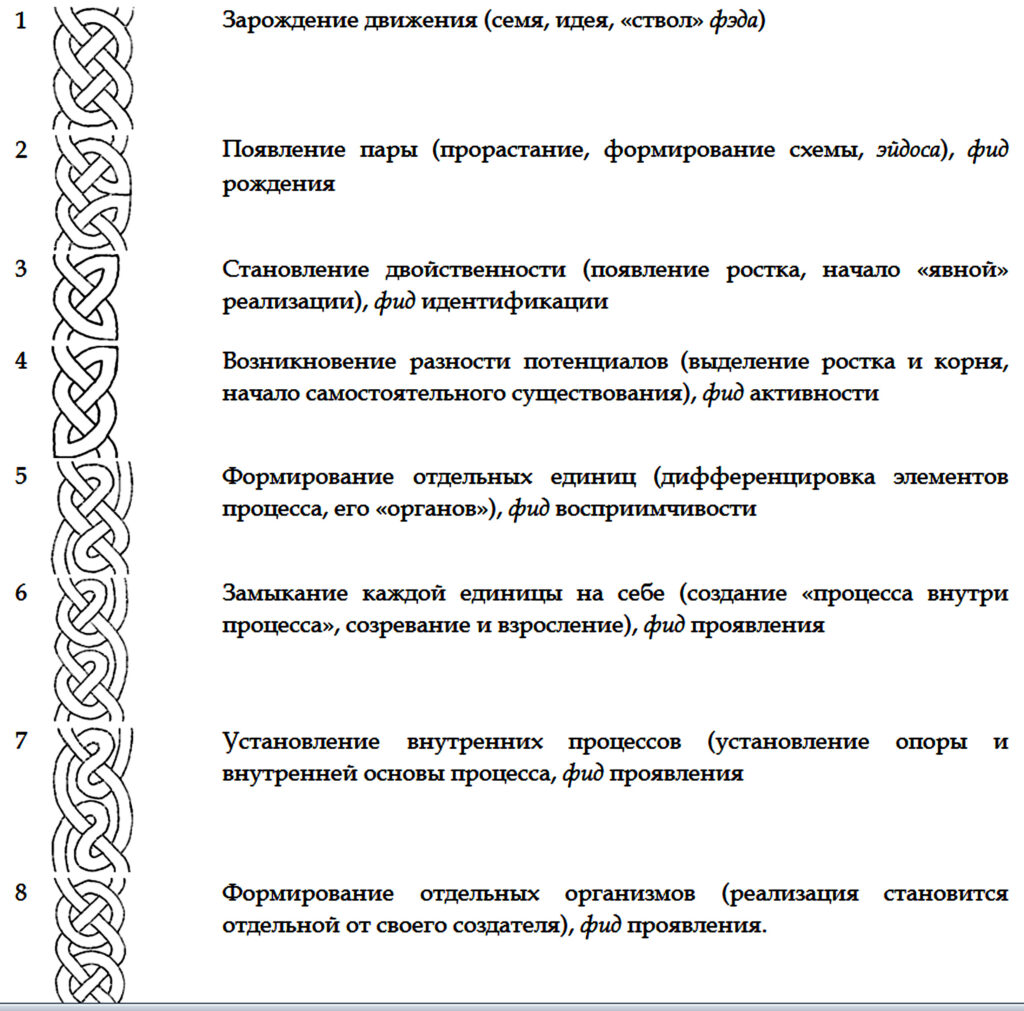

To date, eight “elementary knots” have been described, forming the basis of any “Celtic knotwork”, similar to how eight Runic positions reflect the unfolding of the will vector, as well as two types of weaving — ternary and quaternary — corresponding to the aspects of “spirit” and “matter”. In this case, the figure-eight pattern of knots is formed from the five feda in a regular way: the first knot establishes the space of manifestation, the second–sixth correspond to its stages, and the sixth–eighth specify the ripening of the “fruit”, considering this “fruit” in three aspects of development.

Accordingly, knotwork can be viewed as a “trajectory” of realization, and the creating of such knotwork as setting its course. The use of certain knots from a magical point of view is seen not as decoration, but as an effective technique, yet requiring a clear understanding of the process. Therefore, Druidic training was so long and intensive: it required developing the ability to “include” the student’s mind in the “fabric of processes”, to embed it in the foundation of the creative currents flowing in the depths of phenomenal reality. When druids learned to “talk to trees”, they not only tuned their mind to the “growing” level of the universe — they learned to find this level in any process, read and shape it.

Sometimes I have seen psalms pronounced in the form of a blue vine, with lion heads at the ends. I have also transitioned into this state in church several times, through a sign resembling a cross in a circle. Now I understand that this is Celtic, not Fairy. Yes, my ancestors practiced magic; I did not. It is amazing how Celtic blood reached the depths of Russia.