Eloai and Marbas: The Ignorance of the Digital Age

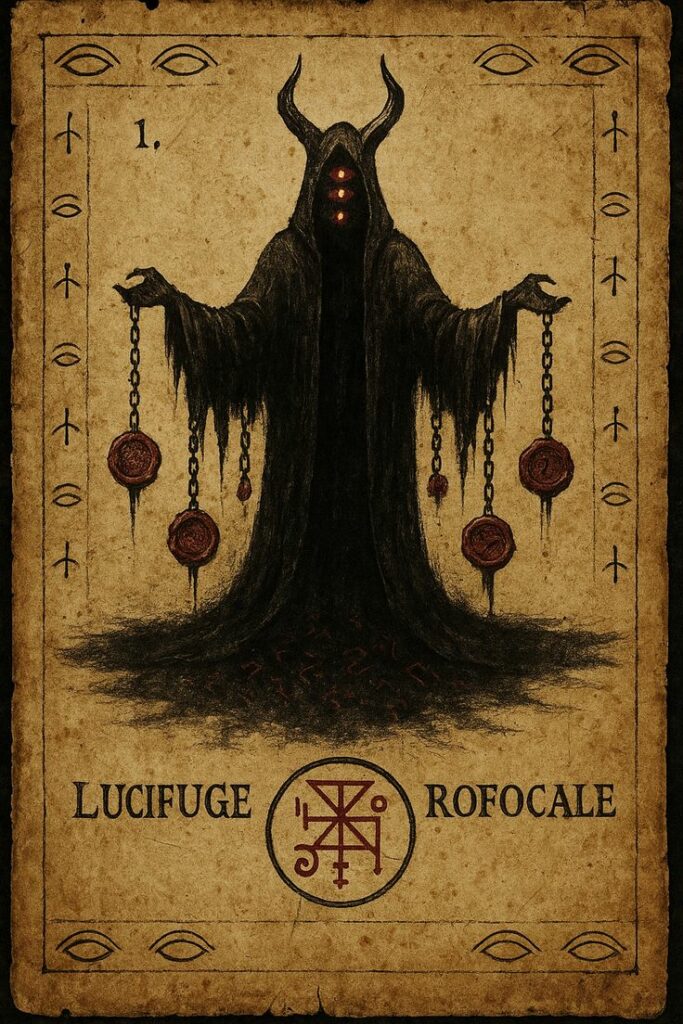

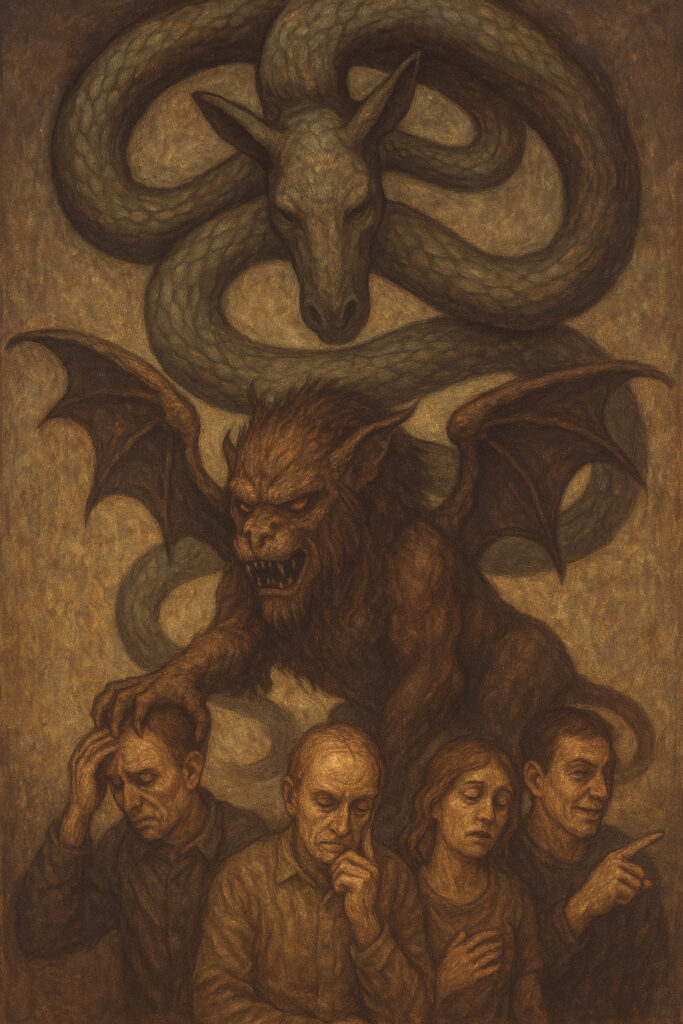

One of the important manifestations of the central destructor of Ignorance is the matrix of Marbas — the “Duke of false expertise,” a mechanism for simplifying and flattening thinking that stabilizes the obscuration “I already know.” This Demon distorts living inquiry into controlled procedures and the habit of delegating thinking — to external algorithms, relying on the activity of the Archon of Mercury — Eloai (who weakens the will to learn) and another archdemon of ignorance — Lucifuge Rofocale (who implants a false “unity and clarity”).

We discussed that the first step of Ignorance is made by King Bael: he “discharges” the very cognitive energy, cultivates the feeling “I already know,” and removes the inner need to ask questions. This is how a new, “obscured” mode of operation of the mind is created: its voluntary refusal of its basic activities and distortion in the very awareness of desires and inclinations.

In this mode, Marbas is the ruler-administrator: he establishes the cessation of cognitive activity as a “new normal,” translating Bael’s false confidence into routine operationality.

That is precisely why he manifests so actively in modern times, with its information-rich digital environment: where multitudes of ready-made answers lie one click away, the “craft of expertise” easily substitutes for actual knowing. Recognizing without understanding — that is the new form of ignorance reinforced by the Duke of the internet.

Therefore, in the retinue of the King of Ignorance, Marbas is the first source of a mechanical halt, when thought doesn’t progress but “rides.”

Among the manifestations of Marbas’s activity, several key aspects can be noted. First, he narrows the acquisition of experience to the binary logic “works/doesn’t work.” Instead of an open field of possibilities, a fixed procedure of “being informed” is established; instead of striving to understand “how it is structured,” the desire to memorize “how to set it up” is cultivated. Second, Marbas establishes the priority of controllability over understanding. Outwardly, this yields ideal “clarity”: the structure of the presentation is plainly visible, the created interfaces are friendly, but inside — there is an absence of a real question; the broadcast image is whole only because everything unsettling, intractable has been removed from it. Third, the Demon changes the source of cognitive satisfaction. Before him, satisfaction comes when understanding has arisen as a result of one’s own work: the mind connected and analyzed facts, checked with one’s hands, made sure, and received dopamine. Under the conditions of an active Marbas matrix, satisfaction becomes consolidated at the level of “received an answer without effort,” and the habit of easy dopamine from an external prompt displaces the longer path of understanding, awareness, and living through real experience.

At the same time, Marbas’s activity, as we have already noted, is “covered” by a more mighty demon of separateness — Lucifuge. His lie is that he declares external supports “highest truth,” “experience,” “the only common sense,” and thus closes the entrance for the light of knowing. Focalor is his instrument of will, a false support in “values” and traditions; Agares turns the mind away from itself — toward other people’s values; and Marbas is his mechanization of the mind: the refusal of living inquiry in favor of ready procedures.

In the digital environment, this triad of destructors manifests especially easily. Lucifuge creates a background of homogeneous darkness: everything seems “one and understandable,” the world — an isolated aquarium without surprises. Against this background, Marbas slips in the form of knowledge instead of knowledge: a shortcut, an algorithm, an answer from the first link, “ask the neural net” — as a replacement for one’s own research. Thus Rofocale’s illusion of unity and Marbas’s “regulated” understanding work together: false unity requires false answers, false answers reinforce false unity.

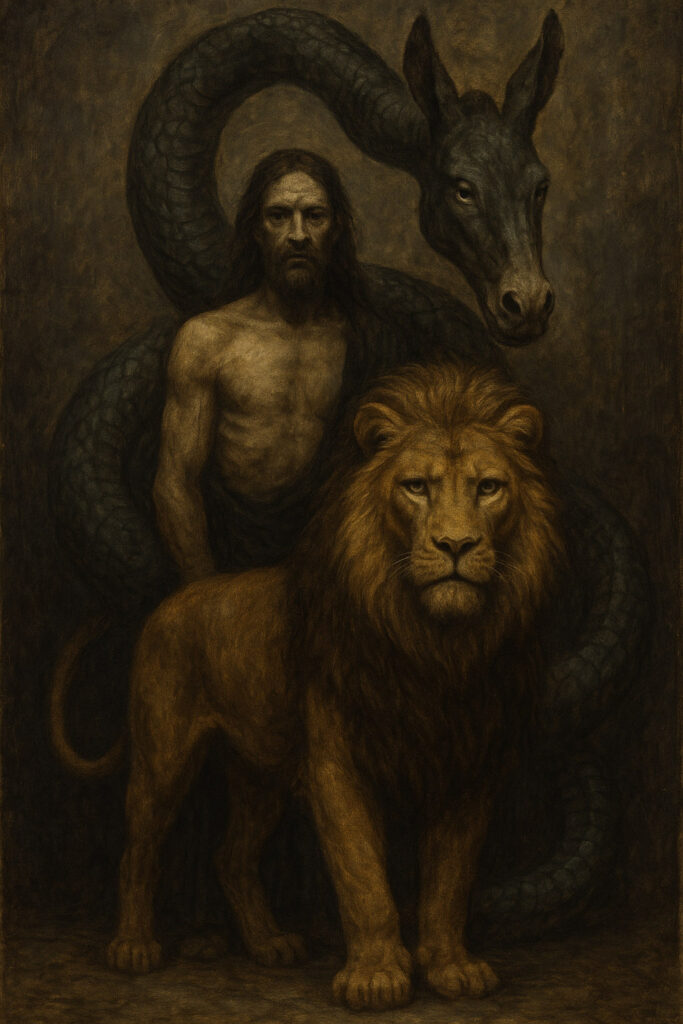

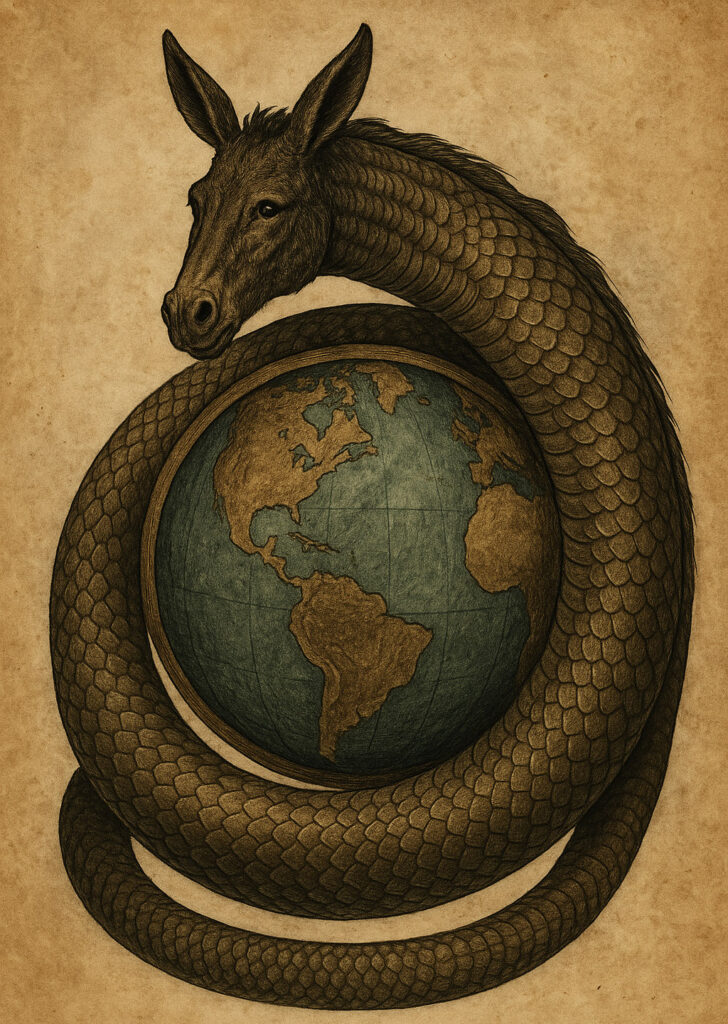

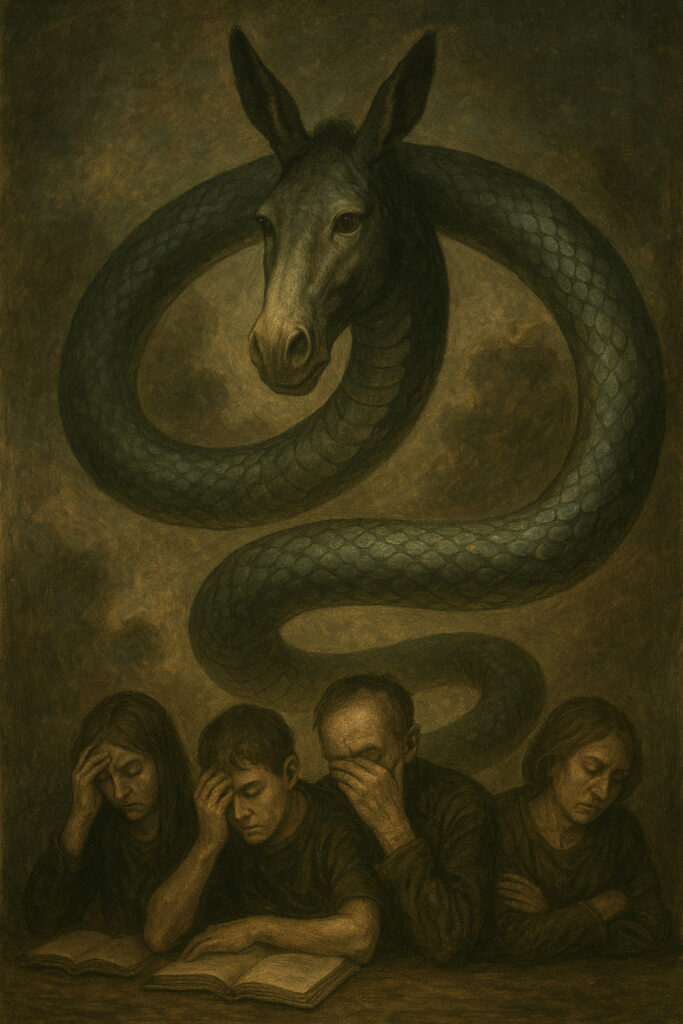

Eloai, the Archon of false reason, ruler of mercurial forces with a donkey’s head, gives this destructor the persistence of habit: “don’t invent, repeat,” “don’t think, search.” Under his influence, thought does not seek a path, but clings to any pre‑laid route. Hence the Archon’s “donkey” head as an image of persistent yet thoughtless following along a trail where the main thing is to go without asking questions: where and why.

Eloai’s adaptability begins with saving mental effort. He quickly finds ways to optimize thinking, puts the mind into an “energy-saving” mode, and hands routine procedures over to technical means. But as it becomes entrenched, this skill becomes the norm of choice: the mind is firmly trained to choose the move with the least resistance. In the psyche, this forms a sequence of simple steps: first, the mercurial flow fixes the result of a successful adaptation: “that worked.” Then it transfers this template to similar situations, gradually narrowing the space of action variants to “what already worked once.” After several such cycles, choice ceases to be felt as choice at all and, in fact, becomes reflexive. Thus a habit forms: “don’t go deep if the task can be solved briefly,” even when “briefly” means “superficially.”

This same adaptability also retunes motivational patterns. Reinforcement becomes not new connections and discoveries, but stable predictability and rapid relief of tension. The cognitive system begins to reward itself for the absence of the discomfort of not knowing, rather than for actually overcoming it. At the level of internal mechanisms, this manifests as retraining of “reward circuits”: less dopamine for searching, more — for confirmation by an algorithm, a habitual action, a familiar solution. There arises a “tolerance for ready answers” and an intolerance for intermediate uncertainty, without which there is no real understanding. Thus Eloai gradually suppresses not only the desire to learn (this is Marbas’s work), but also the very will to learn: the “question” stops rising from within, because the mind has learned to “discharge” it quickly and smoothly enough.

In order to lend credibility to his influences, Eloai renames curiosity as “inefficiency,” detailed verification as “perfectionism,” a delay of attention as a “risk of being late.” Thus the procedural becomes more valuable than the cognitive, and a “correctly followed instruction” becomes the equivalent of understanding. All convictions and habits of the mind begin to reinforce precisely the adaptive choice, rather than the investigative one. In such a system, any attempt to depart from the beaten track already begins to be perceived as an excess and even a violation.

Therefore, in goetic diagnostics, Eloai’s activity can be noticed by two shifts: the will to learning has been replaced by the will to a “faultless procedure,” and the criterion of “good” is reduced to “without effort and on the first try.”

In such a state of mind, it is already easy for the Marbas matrix to manifest. It distracts the mind from the desire to learn, translating knowing into controllability; Eloai holds the mind in this mode, training it to choose the least resistance and suppressing the very impulse to keep the question open until its real resolution.

The activation of Marbas in the mind begins with attention to fatigue, fear of mistakes, lack of time, shame to ask a “stupid question.” Then one hears a thought, as if one’s own: “why reinvent the wheel; let’s see what the web says; let’s hedge with recommendations; let’s ask the model.” And this really sounds reasonable where we are dealing with simple, “linear” questions and information. However, further the Demon gradually and imperceptibly replaces the conceptual system: “to understand” turns into “to find convincing wording,” “to investigate” into “to conduct search operations,” “to verify” into “to cross-check with the context.” Thus, little by little, the cognitive reflex switches to external sources: when faced with difficulty, reason does not want to strain itself, and the one automatically reaches not for primary sources or experiment, but for the search bar or an AI prompt. Clearly, this makes it easy to generate a large number of seemingly reliable answers. And these successes in speed and the reduction of visible errors are reinforced by praise and metrics, and the new norm becomes fixed as “professionalism” or “expertise.” At this stage, the illusion of complete knowledge emerges: the picture seems whole because inconvenient or contradictory elements are systematically excluded. This is followed by a reshaping of identity as well; the desire to truly learn is replaced by the desire to find an answer that seems correct. A persistent aversion to uncertainty develops, as of “inefficiency” and “perfectionism,” and curiosity is recast as a “desire to waste time.”

Thus Marbas blocks the desire to learn, and Eloai strengthens the habit of repetition, reducing tolerance for uncertainty and delay. As a result, even weak impulses to investigate meet inner resistance: “why, if everything has already been invented; there is no point in going deeper; it is an impermissible luxury.” Lucifuge layers onto this an illusion of wholeness and the common-sense rationale of the material: “Everything is clear and works” — therefore “the world is understandable,” and you are smart and successful. Against such a background, any attempt to expand the map looks inappropriate and even dangerously excessive. This is how digital ignorance is formed — a paralysis of inner movement toward real knowledge.

At the same time, it is important to separate two things that are often confused: technological competence and cognitive activity. Marbas actively builds up the first and extinguishes the second. A person may brilliantly wield tools, know rules and regulations, be able to “deliver turnkey” — and yet have long ceased to ask questions. This is the functional “wisdom of craft” that the Grimoires speak of: it is valuable in building bridges and launching mechanisms, but becomes poison where the bridge is declared the world, and the system — the truth. In this toxic mode one can successfully run projects and institutions for years, while remaining in a state of deep ignorance: the outer world works, but inside the mind no longer understands it, though it manages it.

The activity of Marbas can be diagnosed by a number of characteristic signs. The first sign is a shift in the source of proof: “that is the system’s answer” instead of “that is the result of experience/conclusions.” The second sign is a narrowing of the horizon of the mind: “we won’t go further, it’s impractical.” The third is a disruption in goal-setting: simply “so that it works” instead of “so that we understand why it works.”

To oppose the destructor of “ignorance of the digital age,” a simple desire to “think for ourselves” is not enough: Lucifuge, Marbas, and Eloai consolidate not one habit, but an entire web that fetters the mind.

Therefore, it is necessary to break their bonds on several fronts at once. First, one must relearn how to ask questions. It is very important to want “to dig down to the root cause,” to find the deep cause or driver of a particular process or phenomenon, and not simply to find an external explanation. The ability to pose correct questions is, in general, a key ability of the human mind — to seek, to know, not contenting itself with superficial understanding — is a natural trait of the nature of the mind; it only needs not to be prevented from manifesting.

In educational and research practice it is useful to deliberately leave “gaps” — zones that cannot be closed by secondary explanations. To resolve them one must “do it manually”: read primary sources instead of summaries, calculate manually, repeat an experiment with one’s own hands, and so on. In educational practice it is important to assess the reasoning process, work with primary sources, and the ability to designate the limits of knowledge.

In addition, it is useful to formulate the question before searching and verify the answer after: what exactly was being sought and what exactly was found, where the limits of applicability of what was found lie.

Another important skill that helps to oppose the destructor of hidden ignorance is restoring tolerance for uncertainty. One should understand that uncertainty is the original, basic state of the world in which new knowledge is born.

All these skills, in effect, return the rightful place for the Genius Mahasiah. His original nature is to support the ability to ask and to gather. Accordingly, he helps build such a form of work of the mind in which a question has the right to be asked longer than is convenient, “accepted,” or comfortable.

Of course, technical means of searching and summarizing information can and should be used; however, it is important not to give them the function of thinking. Their task is to accelerate the gathering of facts, expand the coverage of sources, and help test hypotheses; however, the task of the mind itself is to formulate questions, build and rebuild models, draw conclusions, and take responsibility for them. It is clear that in the near future all this will be doable by machine minds, but this does not mean that a person needs to or can refuse the independent activity of reason. Living thinking is not only computation, but also the choice of goals, assumptions, and criteria of sufficiency; and it is precisely here that epistemological responsibility lies, which an algorithm by definition does not bear. Without a constant inner process of knowing, the subject itself degenerates, “understanding” is substituted by being informed, and cognitive energy only dissipates, feeding the predators of the Qliphoth and the Interspace.

Moreover, as we have already mentioned, proper coexistence with machines requires robust human thinking: setting nontrivial tasks, checking the limits of applicability, identifying blind spots of data and algorithms. Therefore the right strategy is not to cede the function of thinking but to redistribute labor, when machines excel at fast thinking, coverage, routine checks; however, the human must be capable of formulating questions and evaluating answers, building models, choosing and defining values, and withstanding uncertainties. Thus tools remain tools, and thinking remains the mind’s own function, and neither Eloai nor Marbas have the right to close the question before its true resolution. Then ignorance, even relying on digital powers, is recognized as a pathology, not as a norm or even an advantage.

Hello. Thank you for the article.

It’s a very painful and sad topic, actually. It is quite rare to meet someone capable of a constructive dialogue.

When you try to draw them to specifics or even propose some minimal verification, they immediately raise shields, starting to defend each other with phrases like “I like it this way.” And almost always, without having arguments, they resort to abstraction or some kind of folk wisdom. “To each their own,” subjectivity, etc.

What’s curious is that this procedurality denies other procedures as an undesirable movement and often boils down to these generalizations, even though it seems that ready-made recipes could be quite convenient. But no, we like how the square rolls. 🙂

Enmerkar, this is a very active article. Thank you.