The Legacy of Lovecraft

Modern human history knows many examples where the development of the human spirit was defined not by religious or magical forces, but by the efforts of people — artists, poets — whose work, without intending to, reached beyond the confines of art and became conduits of true magic.

Among such artistic magi — of course — foremost among them are J. R. R. Tolkien, H. P. Lovecraft, F. H. Farmer and others who created their own mythologies, no less coherent and complete than traditional myths.

It is hard to overestimate the transformative influence The Lord of the Rings exerted on the human spirit.

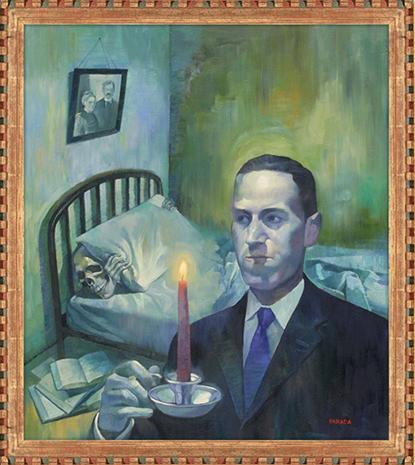

But Lovecraft’s gloomy visions had consequences no less significant. How Lovecraft created, or rather drew from the dark depths of his psyche, parallel realities and other worlds is a valuable lesson for any Magus; few creative people can, using magic and myth in their work, handle that task well.

Lovecraft’s mythology rightly rests on a pseudo‑Sumerian basis — even if it does not reproduce it literally, it certainly inherits and develops the pessimistic mood that colored the outlook of the people of Mesopotamia on the world and their place in it.

How many people searched for the Necronomicon, how many attempts were made to practice grimoirium imperium — and it must be said that the psychological reality of those attempts was considerable, which means that through Lovecraft’s work a new flow of power emerged.

One may argue endlessly about the naivety of such practices, but like other new currents — for example those that flowed from the works of O. O. Speir — Lovecraft’s legacy substantially redirects familiar currents of power in human worldviews, alters worldviews themselves, and therefore changes the world in which the development of the human mind takes place. Isn’t that magic?

From the perspective of magic, the greatest importance lies not in Cthulhu, Azathoth, shoggoths and other mythical figures of Lovecraftian lore, but in its metaphysics. Lovecraft, following C. Fort, introduced the notion of a secret dominant of Being — “Lo.” Everything, every living creature carries Lo within it, but its destructive activity (and the action of Lo is always destructive) manifests only in contact with the magical continuum. Sometimes, for reasons unknown, certain objects, landscapes and sounds can awaken Lo’s activity.

“It is difficult even to imagine that one species of tangible and dimensionally accessible object can so shake a man: apparently, in some outlines of objects lives a secret imperative symbolism which, by distorting the perspective of a sensitive observer, births in him an icy foreboding of dark cosmic relations and vague realities concealed behind the ordinary protective illusion.” (The Case of Charles Dexter Ward).

And the trace of the terrible “secret dominant” runs through almost every story by Lovecraft.

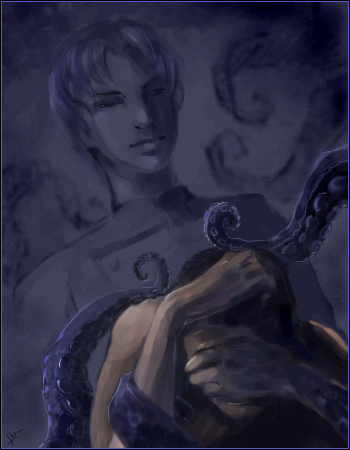

Such ideas have an important consequence in the form of doubts about the very existence of the self. In the psychosomatic complex described by Lovecraft there is always the potential for final annihilation and radical transformation, which means that talk of any centralized unity is meaningless.

Human laws do not coincide with the laws of the universe, and in Lovecraft’s tales the theme of the futile struggle of insignificant, complacent humanity to comprehend the meaning of the Universe and to hold back the horror from beyond is repeated again and again. Unlike a magus who actively seeks contact with the inhabitants of the Abyss, Lovecraft recoiled in horror and awe before what invaded him in his sleep.

Doubt about the existence of one’s own ‘self’ prevents Lovecraft’s protagonists from attributing even a hostile will — they feel at the mercy of vague forces, energies, fields and the like. Occasionally they manage to learn the name of a powerful source of these influences, but after a while that concreteness dissolves again. Drawn into the play of unknown transformations, acknowledging chaos as the highest manifestation of human wisdom, Lovecraft’s heroes go mad and perish in subterranean and cosmic labyrinths.

For Lovecraft the only way to rationalize the knowledge he gained was to clothe it in fantastic forms and to expel what he could not understand.

The division of the world into a hierarchy of Hell, Earth and Heaven, a transcendental exit beyond the visible world, the acquisition of supernatural abilities — all this, in Lovecraft’s view, is only a dream.

For him

“every religion is merely a childish and absurd glorification of the eternal, aching call in the boundless and provoking void.”

Lovecraft was categorically opposed to any manifestation of romantic heroism — triumphs of good over evil, and so on. The idea of a possible organic unity independent of external influence he found inherently absurd.

His stories constantly remind the reader that humanity stands only a short step away from the most vile and malevolent forms of life. This theme of the permanent interaction between the creative and destructive aspects of human personality is a cornerstone of Lovecraft’s conception.

And as in many such cases, Lovecraft’s own ideas are sharply different from what they became in the minds of the followers of the movement he initiated. Just as Crowley became the precursor of many dark movements, Lovecraft initiated the fascination with chaos which has many adherents today.

Note that from the standpoint of traditional magic, Lovecraft described the dark side of dreaming — a world of potential reality where both constructive and extremely destructive forces and manifestations may exist.

Regardless of how we judge Lovecraft’s work and his insights and theory of potential chaos, one must acknowledge his talent and his ability to redistribute power, and the chief lesson for every Magus in this story should be the confidence that he can create his own viable myth and act within it — if none of the existing myths suit him.

A question immediately arises in the context of the existence of Archons: where does this redirected Stream of Power flow? Does the world-myth created in dreams and fantasies lead this Stream of Power to the Space of Dreams for nourishing the Guardians of the Between Worlds?

You are thinking in the right direction 🙂 It is precisely because a mage should not give Power to the Archons, in contrast to the visionary-mythmaker, that they must clearly control themselves and the streams of Power they create.

Mage-visionary-mythmaker – what is the desired degree of control over Power in this case (in your terminology)?

The source of Power for a Myth can be both internal, controlled by will, like in a mage, and external fluctuations (external relative to daily consciousness, though their source can also be the depths of the Psychocosmos) – like in a visionary. However, both can create a stable Myth. The only question is where this Myth leads those who walk in it.

🙂 Indeed, the Purpose is important

Thank you.

I adore Lovecraft!!! His books are filled with Power; I have long considered him a magician, so it’s nice to read your article today and find out that you essentially share this view.

If you look closely, then perhaps there are no modern myths that are as distant from each other as Lovecraftianism and Thelema. It is no coincidence that Thelema appeals to an optimistic Egypt, while Lovecraftianism – to a pessimistic Mesopotamia. Indeed, Thelema proclaims that every man and every woman is a Star, that everyone has their own Path, Purpose, Meaning. Everyone has their own core, their own axis, etc. The Lovecraftian myth denies all of this. And asserts that within human nature, there is no constant at all. Nevertheless, there was a person, probably one of the first, who saw in H.P. Lovecraft not just a writer, but an unconscious prophet, who somehow connected both myths. This is the recently departed Kenneth Grant. How he managed this, he took with him to the grave. It’s as if he took a tailor’s scissors and cut up Thelema. Then he cut up Lovecraft. And stitched them into something called the Typhonian Myth. Of course, every myth has the right to exist. The question is, what percentage of the threads used to stitch pieces from different myths to create a new myth are white?

I remembered N. Oleinikov: ‘I was surrounded by familiar things and all their meanings were ominous.’ Lovecraft was recklessly brave; there are other realms in the world that can only be designated by one’s own demise. A person has nothing to oppose them; reason is too weak and tangled, and Eros does not work in these realms, cannot protect. It turns out that the tree of sephirot is merely a blade of grass at the edge of the abyss, and our ‘ascents’ and ‘transfigurations’ are the futility of deathly frightened bugs crawling on this tree. The most unpleasant fact is that neither will, nor courage, nor beauty, not to mention knowledge, hold any significance for the abyss.

But they matter to me, and that’s the only thing that matters. )

Enmerkar, good afternoon! I have a question about the works of P. Bazhov; what do you think of his tales from the perspective of magic, myth? If it’s not too difficult or out of place, can I learn about your attitude toward Ural tales?