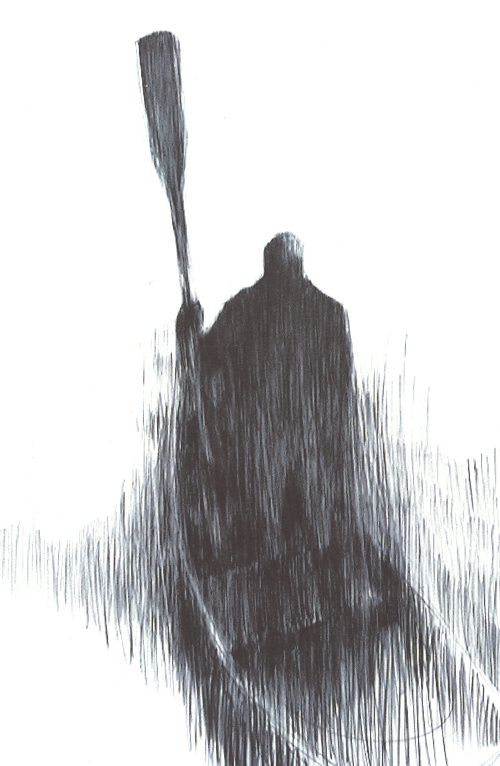

Ferryman of Souls

In our discussions of disembodiment we have already mentioned the somewhat grim figure needed to cross the Threshold of Worlds. Many peoples pictured the Threshold as a river, often a fiery one (for example, the Slavic Smorodinka River, the Greek Styx and Acheron, and the like). In that light, it is understandable that the creature conveying souls across this boundary was frequently pictured as an ferryman.

This is the River of Forgetfulness, and crossing it signifies not only the soul’s movement from the world of the living to the realm of the dead but also the severing of all ties, memory, and attachment to the world above. Therefore it is a river of no return — there is no reason to return. Clearly, the Ferryman’s work in severing these ties is critical to the process of disembodiment. Without him the soul will be repeatedly drawn back to places and people dear to the deceased and will therefore become an utukku — a wandering corpse.

As a manifestation of the Great Guardian of the Threshold, the Ferryman of Souls is an indispensable figure in the drama of death. Note that the Ferryman is a one-way guide — he conveys souls to the realm of the dead but never (with the exception of rare mythological anomalies) returns them.

The ancient Sumerians were the first to recognize the need for such a figure, a role filled by Namtarru, emissary of the queen of the underworld Ereshkigal. At his command the demons known as the Gallu seize a soul and carry it off to the realm of the dead. It is worth noting that Namtarru was the son of Enlil and Ereshkigal, and thus occupied a fairly high position in the hierarchy of the gods.

The Egyptians likewise widely used the ferryman image in their accounts of the soul’s posthumous journey. This role, among others, was attributed to Anubis — Lord of the Duat, the first realm of the afterlife. There is an interesting parallel between the dog-headed Anubis and the Grey Wolf — the guide to the otherworld in Slavic tradition. Moreover, it is no accident that Semargl, god of the open gates, was also depicted as a winged dog. The form of the guardian dog of the worlds is one of the oldest attempts to grapple with the dual nature of the Threshold. Dogs often served as soul-guides and were frequently sacrificed at tombs to accompany the deceased on the road to the other world. The Greeks adopted this guardian role in the figure of Cerberus.

Among the Etruscans the Ferryman was initially embodied by Turms (the Greek Hermes, who retained this psychopomp role in later mythology), and later by Charu (Harun), who apparently was perceived by the Greeks as Charon. Classical Greek mythology differentiated the idea of the Psychopomp (the “Guide” of souls responsible for guiding souls from the living world, whose importance we have already discussed) from that of the Ferryman, who acted as a guardian — gatekeeper. Hermes the Psychopomp in classical myth seated them in Charon’s boat. It is interesting that Hermes the Psychopomp was often portrayed as cynocephalic — dog-headed.

The old man Charon (Χάρων — “bright,” meaning “shining-eyed”) is the best-known personification of the Ferryman in classical mythology. The name Charon first appears in one of the poems of the epic cycle, the Miniad. Charon ferries the dead across the waters of the underworld rivers and is paid one obol for the passage (a burial custom in which the coin was placed under the tongue of the deceased). This practice was widespread among the Greeks not only in the Hellenic but also in the Roman period, persisted through the Middle Ages, and survives to the present day. Charon carries only those dead whose bodies received proper burial. In Virgil, Charon is a dirt-smeared old man with a dishevelled white beard, fiery eyes, and ragged clothes. Guarding the waters of the Acheron (or the Styx), he uses his pole to ferry shades in his skiff — some he admits to the boat, others, those unburied, he drives from the shore. Legend says Charon was once chained for a year for having ferried Heracles across the Acheron. As a denizen of the underworld, Charon later came to be regarded as a demon of death: under the names Charos and Charontas he passed into modern Greek folklore, who depict him either as a black bird swooping down on its prey or as a rider chasing a throng of the dead through the air.

Northern mythology, though it does not emphasize a river encircling the worlds, still recognizes it. On the bridge across that river (Gjöll), for example, Hermod meets the giantess Modgud, who admits him to Hel, and it seems that across this same river Odin (as Harbard) refuses to ferry Thor. It is interesting that in the latter episode the Great Aesir himself assumes the role of Ferryman, which underscores the high status of this typically inconspicuous figure. Furthermore, the fact that Thor found himself on the opposite bank suggests that, in addition to Harbard, there existed another boatman for whom such crossings were routine.

In the Middle Ages the idea of transporting souls developed further and continued. Procopius of Caesarea, historian of the Gothic War (6th century), relates an account of how souls of the dead are sent by sea to the island of Brittia: “Along the mainland coast live fishermen, merchants, and tillers of the soil. They are subjects of the Franks but pay no taxes, for from time immemorial they have borne the grave duty of ferrying the souls of the dead. The ferrymen each night await in their huts a customary knock at the door and the voice of unseen beings calling them to their task. Then the people immediately rise from bed, moved by an unknown force, descend to the shore, and find boats there — not their own, but strange boats, fully ready to put to sea and empty. The ferrymen take their places in these boats, seize the oars, and see that, from the weight of the many invisible passengers, the boats sit deep in the water, within a finger’s breadth of the gunwale. In an hour they reach the opposite bank, whereas in their own boats they could scarcely have made the passage in a whole day. Upon reaching the island the boats unload and become so light that only the keel touches the water. The ferrymen see no one on their way or on the shore, but they hear a voice that names the name, rank, and kin of each arrival, and if it is a woman, also the rank of her husband.”

Christianity introduced the image of the Angel of Death to explain this aspect of dying, often known by the name Azrael (Hebrew meaning “God helps,” also Abaddon — the Angel of the Abyss). In Christian tradition the archangel Gabriel is sometimes called the angel of death. In any case, the necessity of a being to help overcome the threshold between life and death is acknowledged.

Thus, in addition to the Guide who helps the soul cross from life to death, this process requires a figure who makes the process irreversible. It is precisely this function of the Ferryman of Souls that makes him the darkest figure in the process of dying.

Nowhere was it mentioned that there can be more than one carrier (for example, one main and two assistants)?

I would like to thank you for this good article!! I loved every piece of this text. I bookmarked it to see the new articles you will write.