What Was Known About Faerie in the East

Faerie, known in European traditions as Aes Sídhe, Tylwyth Teg, sídhe and their individual races and peoples, were no less widely described in Eastern cultures. In Japan they are called yōkai, in China — yaoguai, and in a broader sense — yao (妖), meaning “wondrous beings” or “mystical creatures.” Despite the difference in names, we are speaking of the same category of beings — an ancient people living on the border of worlds, endowed with magic and following their own way, distinct from the human one.

We have already mentioned that in the West, faeries were often mistakenly conflated with nature spirits — elementals, nymphs, leshiy, and vodyanoy. In the East as well, yōkai were described as beings that, though similar, were not identical to local spirits. It was known that they could change their dwelling, wander, and interact with people. They exist physically, even if their bodies do not always obey human laws of nature. In addition, yaoguai were described as magical beings capable of evolving: they may be born as animals, but over time become wiser and more powerful, and some reach the level of deities.

As in descriptions of faerie, yōkai and yaoguai eat, sleep, fight, transform, and leave remains behind if they die. They can lose or accumulate strength and change their nature, but they never vanish without a trace like immaterial spirits.

As we also mentioned, faerie are always drawn to places where the energies of nature are in balance. They weave themselves into existing natural rhythms, preserving natural harmony. In the East, yōkai and yaoguai were characterized in the same way; some of them guard places of power as guardian beings; however, they do so of their own will, not by nature. Others master the human world, penetrating villages and cities while always preserving their otherness. Still others wander between worlds, appearing where energies are most saturated.

They possess intuitive knowledge of energy currents. As in Europe, they settled near springs, in ancient forests, avoiding places where natural forces are diminished. For example, in Japan tengu (mountain yōkai) lived in deep forests and on the slopes of sacred mountains, since these places preserve the purest energy. In China, fox-hulijing also always chose areas with strong qi in order to nourish their shapeshifting abilities.

Magic and cunning are natural qualities of faeries (yōkai). In both Western and Eastern traditions, the people of the Faerie world are known for their wit, craftiness, and play with the perception of reality.

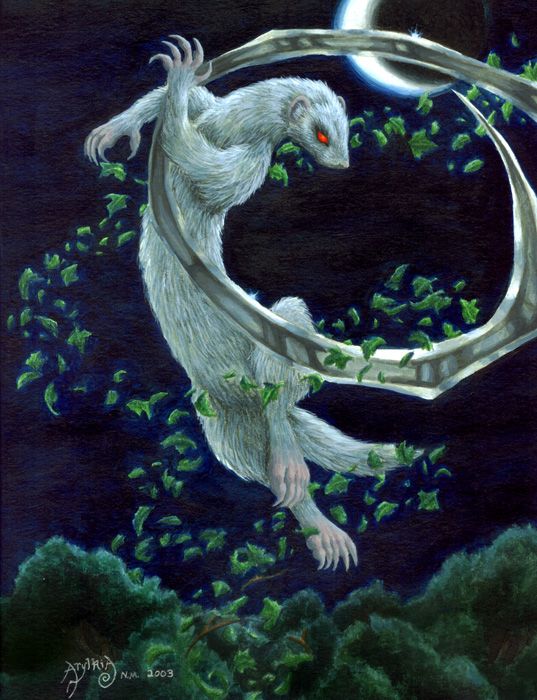

Many faerie peoples are capable of leading a person into illusions in order to hide from their eyes. Yōkai, for example, nue or kamaitachi, frighten people by appearing suddenly and changing their form. Yaoguai know how to conceal their essence by taking the form of beautiful girls or wise old men, just as elven kings can appear to people in the guise of old men with a piercing gaze. In descriptions of both faerie and yōkai, it is emphasized that they are not unambiguously good or evil — they themselves decide how to act in each case.

Some of them help people — Japanese zashiki-warashi bring luck to homes, and Chinese lanmiao (cat yaoguai) guard temples. Others lure people into traps — for example, skatachi can drag a person into the Interworld, and nukekubi (Japanese shapeshifters) at night detach their head from the body and suck out the victim’s life force.

Still others like to make deals — Japanese onibaba can grant a wish in exchange for a terrible price, just as bendith y mamau in Western lore demand children or part of the soul in return.

Thus, in descriptions of both faeries and yōkai, it is very clear that they possess flexible morality. They act by their own laws, which are not always understandable to people.

We have already noted that many faerie peoples feed directly on natural energies, absorbing them from the elements — earth, water, air, and fire. Their survival is closely tied to the condition of the world around them. They do not need food in the human sense, yet they can absorb the energy of people and animals as physical strength, emotions, and luck.

This was also noticed in the East. It was noted that some yōkai and yaoguai absorb fear and faith (they become stronger if people talk about them). Others feed on mental energy, like tsukumogami (ensouled objects). Some literally drink life force, like Chinese hulijing that suck out qi.

In Eastern traditions it was also noted that representatives of the Faerie Peoples can develop and become gods. For example, fox-hulijing, upon reaching 1000 years, turn into heavenly spirits. And yaoguai who have followed the Taoist path can attain immortality. Yōkai who have accumulated wisdom sometimes become protectors of nature or patrons of villages. Their wisdom and magic grow along with their age.

Both in the East and in the West, it was known that faeries are not nature spirits but an entire distinct people existing on the border of worlds. At the same time, in all cultures the general group of “Faerie Peoples” often included other beings as well — for example, elementaries that came into the manifested world (in the East they were called kunitsukami) and escaped utukku (yūrei), yet there was still an understanding that the main property of yōkai is their own corporeality. They can be wanderers, like many yōkai; guardians of natural places, like hulijing and tengu; cunning players making deals, like some yaoguai.

Descriptions of typical yaoguai abilities practically coincide with what is known about faeries in Western traditions.

They are amoral, but not without morality; they can be capricious and unpredictable, but they are not absolute villains. As in descriptions of faerie, in Eastern tales about yaoguai it is noted that they can experience emotions, fall in love with people, repent of their deeds, and change their nature.

They can help people, but they can also take revenge, joke, or behave indifferently, and in general do not obey a clear system of good and evil; their actions are determined by circumstances, desires, and personal sympathies. Their morality is based on their own notions and is more connected with the natural cycles of births, transformations, and deaths than with cultural constraints.

At the same time, in the East it was noted, yaoguai, especially of animal origin, strive to acquire a human form and sometimes live among people. As in the West, yaoguai often fell in love with mortals and created families with them, but their non-human nature remained unchanged.

One of the most interesting features of these beings, noted both in the West and in the East, is their dual nature: they are not gods, but they are older and wiser than humans and can possess colossal power; they are not spirits, but they can transform, becoming closer to deities.

Among them there are also those who consciously strive for greater strength, wisdom, perfection, or — on the contrary — degenerate, losing their connection with Magic.

Many of them have the ability to change their appearance. They can transform into animals, take on human form, or become completely unrecognizable. In the West, faerie are especially often mentioned who take the form of beautiful women to lure travelers, or turn into shadows, animals, mirages. In the East, this ability is considered especially characteristic of animal yaoguai, who strive to acquire human form. For example, legends tell of fox-hulijing who disguise themselves as women, or magical tigers taking the form of monks.

Many faerie peoples are capable of bewitching mortals, creating mirages, changing the perception of reality. For example, in Western legends enchanted castles, feasts whose food turns out to be leaves and stones, or visions that lead people off their path are often encountered. In Chinese and Japanese legends it is also noted that yōkai and yaoguai are capable of deceiving people’s perception, making them see non-existent cities, ghostly landscapes, or distorted versions of reality.

In the West it was noted that many faerie can captivate the mind of mortals, leading them into the Interworld. This is especially characteristic of the beings of the Seelie Court, who lure people into their round dances and caves. In addition, it is believed that faerie can bring on sleep, forgetfulness, and in darker legends — drive people mad. In the East it was also known that such beings are capable of taking possession of a person’s mind, turning them into their puppet or instilling false desires. For instance, those same fox-hulijing are capable of charming men and subjugating them to their will.

In Europe it was noticed that the High faeries possess knowledge of the past, present, and future. For example, banshee foretell death, and many High sídhe are able to see people’s destinies. In the East it was also observed that many yaoguai, especially those who have attained spiritual perfection, possess the gift of prophecy. In Chinese lore, wise yaoguai who foretell the future or read destinies are not uncommon.

In Western lore it is noted that people abducted by faeries can be enchanted, forget their former life, and remain forever in the faerie domains. Also, faerie can “curse” a person, changing their perceptions and thoughts. In Eastern stories it is also said how yaoguai can literally take possession of people’s bodies. For example, serpentine or fox yaoguai inhabit women, making them bearers of their power.

Both in Europe and in Asia, it was known that control over natural forces is one of the most important abilities of faerie. They can call down rains, freeze water, command winds, make the earth fertile or barren. Many faerie are connected with certain natural phenomena, closely interacting with gods and elementals. In China it was also said that yaoguai can control the elements — for example, dragons command rains, and others among them can change the weather, bring droughts or hurricanes.

Thus, since ancient times people in both Europe and Asia knew that they are not the only intelligent beings inhabiting this world. Practically all peoples have legends about the Second Humanity — a hidden people that exists nearby but separately from humans. They are neither gods, nor demons, nor spirits, but represent a different kind of corporeal being, whose nature is closely connected with natural forces, Magic, and a special mode of existence. These beings in different parts of the world were called differently — faerie among Europeans, yōkai among the Japanese, yaoguai among the Chinese, devas among the Persians, apapatsuaq among the Inuit — but their essence always remained similar.

Both in the West and in the East, the Faerie Folk were perceived as ancient inhabitants of the world, a people parallel to humanity, who cannot be clearly called “benevolent” or “malicious” — they were always unpredictable, like nature itself, and their society operated by its own laws and moral norms different from human ones. Perhaps, if humanity again seeks harmony with the world, the old paths will open once more, and contact with the Faerie folk will be restored.

Hello! If fairies are beings of the “maternal” path of consciousness, integral and immanent by nature, does this mean that their duality and ambiguity for humans arise not from any internal contradiction on their part, but from the fact that it is humans who try to perceive and interpret their behavior through their own value system, divided into “good” and “evil,” “creation” and “destruction”? In other words, it turns out that fairies are actually mirrors for humans, reflecting not so much their own nature as human concepts and fears?

Andrew, thank you for your comment and questions; I find such reflections very close to me, and I’m very interested in getting to know Enmerkar’s perspective.

Hello! Fairies are originally, beings not only of morality but primarily of pure nature and flow. Their behavior always reflects natural wholeness and a striving for inner balance; however, it is alien to human morality, with its division into clear categories of good and evil. People often perceive the behavior of fairies as “ambiguous” simply because they evaluate it from the standpoint of human logic, morality, and desires, which often contradict the laws of nature and harmony. Fairies have always been and remain teachers of subtle boundaries: they can be generous and wise mentors, capable of elevating a person’s consciousness to an entirely new level, but at the same time, if a person crosses certain boundaries, displays arrogance or a consumerist attitude, they can show their dark, destructive side. In some sense, their “ambiguity” reflects the mirrored nature of reality itself—the way a person manifests toward them determines their response. That is why, in both Eastern and Western cultures, the attitude toward fairies (yokai, yaoguai, sidhe, and other “boundary” beings) is so similar in essence: they are described as beings capable of both helping and harming, both mentoring and punishing. They are immoral because they do not judge the world by rules set by humans, yet at the same time, they are deeply ethical as they follow the natural laws of harmony and balance. The fear of humans towards fairies arises not so much from their real danger (though such danger is possible) but from the depths of human nature: people fear uncertainty and the unknown, fear losing control over a situation, over their own consciousness, over the world around them. Fairies, by their very nature, are boundary beings that have always existed simultaneously in the manifested world and in the Interstice, in the space where familiar human understandings of the world, logic, and boundaries cease to operate. They are the embodiment of the unknown, chaos, and ambiguity; they remain “one foot” in a world where humans have no customary anchors. Encountering fairies is always an encounter with uncertainty. They can change form, play with perception and consciousness, cross the boundaries of reality. For human consciousness, this induces immense discomfort as our psyche strives to categorize and structure everything. When the world suddenly turns out to be multifaceted, fluid, and elusive, the psyche begins to panic. Moreover, fairies reflect what humans subconsciously suppress: the chaotic nature, the unbridled instincts, the internal darkness. People fear what does not conform to their understanding and control because it signifies a loss of safety. Therefore, fairies, who always remain “other,” even when friendly, evoke primal, irrational fear. For a magician, interacting with them becomes particularly productive precisely when they abandon the evaluation of their behavior from a human perspective and, indeed, begin to perceive them as mirrors of their internal state and attitude toward the world. Overcoming the fear of uncertainty, integrating what we suppress and do not wish to see, makes consciousness more whole, and a person wiser and stronger.

Humans are weak, foolish, and, in general, vile, but it is precisely with them that one can suffer and laugh heartily, to the fullest. ))

I used to think that the information about bad Fairies originated from bad people who deserved to suffer.

Very interesting. Thank you.

And who are the fairies in Russia? If in the east they are yokai, and in the west – sidhe, then in Russia they are leshiy, vodyanoy, baba-yaga? Is there a common name?

No, neither leshiy nor vodyanoy – they are not fairies; they are nature spirits, elementals, and spirits. Fairies in Rus’ were called ‘divye lyudi,’ and among them are known anchutki, igretsy, kuzutiki, kulyashi, and so on. All of them gradually came to be considered something like ‘lower unclean spirits,’ devils or demons, but at their core, they are similar representatives of the Magical people.