Is There Light at the End of the Tunnel?

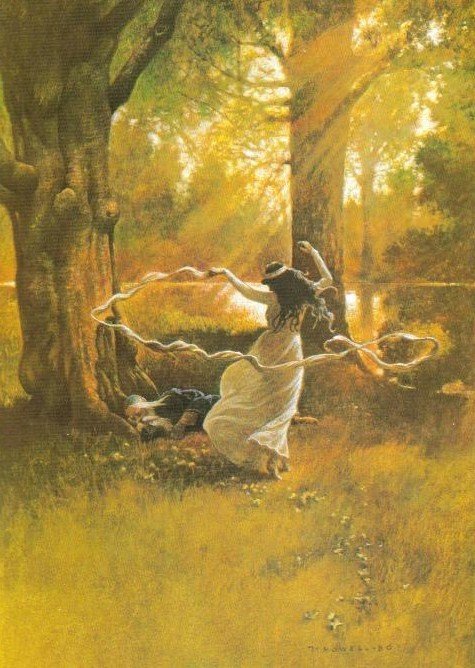

When a person discovers their Way — and often when they merely believe they have — they are swept by waves of optimism. It seems to them that universal Wisdom is within reach; they feel enlightened and awakened.

The same sensations often visit those who do not even intend to seek a Way, because they believe that life itself is the Way and that all that is needed is to “self‑improve,” to “grow spiritually” during this life.

This attitude toward life and the Way became especially widespread after the so‑called “psychedelic revolution” of the 1960s–70s, which spawned a powerful movement in transpersonal psychology and neo‑shamanism in the West.

Typical statements by proponents of this current include:

“It seemed to me that on a very deep level I was connected with all life on the planet… I felt a cosmic quality in the energies and experiences common to all forms of life… as well as a drive toward self‑expression… operating on many levels,” “I met pure consciousness, the Universal Mind, and creative energy that transcended all distinctions… I merged with the Source as one,” “I felt the breath of eternity touch me…” (from the works of S. Grof)

and the like.

For the modern neo‑spiritual tradition, such a blissfully optimistic view has become typical. Life is presented as a “school,” and the afterlife as a “merging with the Universal Mind.” This mindset makes existence unusually easy by shifting all problems and difficulties into the psychic realm, labeling them “complexes” or “engrams” and creating the impression that overcoming them requires just a little effort.

This so‑called positive thinking has become widespread through the combined efforts of the film industry, television, popular music, self‑help books, and Sunday sermons: “Everything will be fine! All problems are solvable! Be optimistic and success is assured. Optimism is the key to success, wealth, and invincible health.”

At the same time, it is clear that such a one‑sided view of the world and of oneself does not present a realistic picture of what is happening. By adopting it, a person inevitably lives only for the present, without considering the consequences of their own or others’ actions. Carelessness and egoism are the first fruits of thoughtless optimism, and it is precisely these that we see flowering in the modern world.

Millennia‑old traditions of Magic and the Occult are dismissed as the “childhood of the mind,” and centuries‑long lineages of magic are labeled as “failing to grasp the beauty and harmony of the cosmos.”

Moreover, to any sober mind it is obvious that people three hundred, five hundred, or a thousand years ago were not less intelligent than people today. Why, then, are traditional magical conceptions far less optimistic?

Not only were Mesopotamian civilizations imbued with grim pessimism; it even affected the otherwise cheerful Greeks, who, according to B. Russell, argued roughly as follows:

“Being — fundamentally elemental, not begotten by reason but itself giving birth to reason — places the element above reason; and man, feeling himself by reason a divine element, wants to secure himself against the power of the material, chaotic element. For this he seeks to join with Dionysus. But even aside from the fact that Dionysus in orgiastic cults is a deity of elemental forces, the very powers from which man wishes to be freed — he, even in the understanding given him by Orphism, had already once been devoured by the Titans. What assurance is there that they will not devour him again? Dionysus rests on the power of Zeus, but Zeus’s sovereignty is not firm and, in the view of the Hellenes, has an end.”

Finding no better consolation in Orphism, the Hellenic mind nonetheless could not be appeased by it.

Indeed, Homer already says:

“Men are like leaves on the trees of the oaks: one wind scatters them across the earth, another grove, spring returning, bears them again, and with the new spring they grow; so men: some are born, others perish.”

Pessimism permeates all Greek lyric poetry.

Indian thinkers, so venerated by modern adherents of “cosmic consciousness,” established that “life is suffering” and “the cause of suffering is life itself.” Indian philosophy is pessimistic in the sense that its works are suffused with a feeling of dissatisfaction and anxiety about the existing state of affairs.

We observe a similar train of thought among Magi throughout the history of Western civilization. According to their conceptions, pessimism as a force and stronghold harbors no illusions, sees dangers, and refuses to whitewash or gloss over anything. It analyzes phenomena in depth; it demands clear awareness of those conditions and forces which, despite everything, will nevertheless allow one to master the historical situation and secure success.

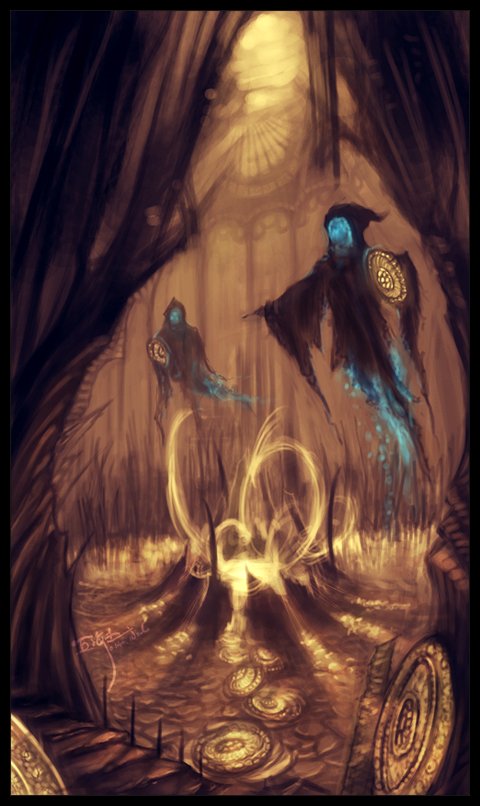

In their lives Magi confront forces far greater than their own, and they often enter into confrontation with these forces. Unlike modern neo‑shamans, Magi interact with these powers not only in an “altered” but also in the waking state of mind, when critical vision is not switched off and the capacity for analysis is not suppressed.

And it is precisely for this reason that practicing Magi know well that, in truth, the chances of victory are negligible.

Having spent their lives fighting for the right to be themselves, to act of their own will rather than be playthings in the hands of “cosmic” predators, Magi see that the afterlife is by no means the bright “merging with the World Mind.” Their experience shows that many of those who have died do not even realize they have died; their mind — the dream mind — continues to function in that mode and gradually disintegrates. Individuality, undeveloped during incarnations, cannot provide an anchor to preserve the “I,” which likewise dissipates into the world’s order, offering its mind as food to the World Predator.

As a result, the next incarnation is only weakly connected with the previous one, linked mainly by the tasks it must resolve.

Moreover, the afterlife of Magi themselves often proves even more tragic: having entangled various ties with people, powers, and spirits, a Magus frequently becomes trapped in the afterlife, deprived of the flow of power and tormented by their “creditors.”

But it is not only the afterlife that gives the Western Magus little cause for optimism. As soon as one sets foot on the Way and the initial euphoria subsides, one almost immediately encounters furious resistance from external and internal predators; it seems as if the whole world has rallied against one and seeks to crush, destroy, or at least force one off the Way.

And it is not surprising that the number of Magi who have won the battle for themselves — for their selfhood and their freedom — is vastly smaller than the number of those who have lost, who have forfeited the Way, power, and themselves.

Thus, for a Magus it is obvious that the chances of changing the situation are minuscule. Yet they do exist. Or, as one Latin American writer puts it, there is a “chance to get a chance.”

Therefore the struggle is not meaningless, although it is almost hopeless. Moreover, for the Western Magus it is evident that, given the choice — to perish in battle or to die in one’s bed in deep senility — the first option is far preferable.

The moment comes when it is necessary to challenge Power, but where to find the strength? Immersion in illusion raises doubts…

The whole life of a magician is precisely – preparation for this Final Battle…

The final battle… After it, one can surely relax))

:)) let’s put it this way – the last one for a person as he is 🙂

“…Rather better to measure your strength against the storm,

To give your last moment to struggle,

Than to get to the quiet shore

And count your wounds mournfully.”