“The Evil God” in the Mythology of Europe

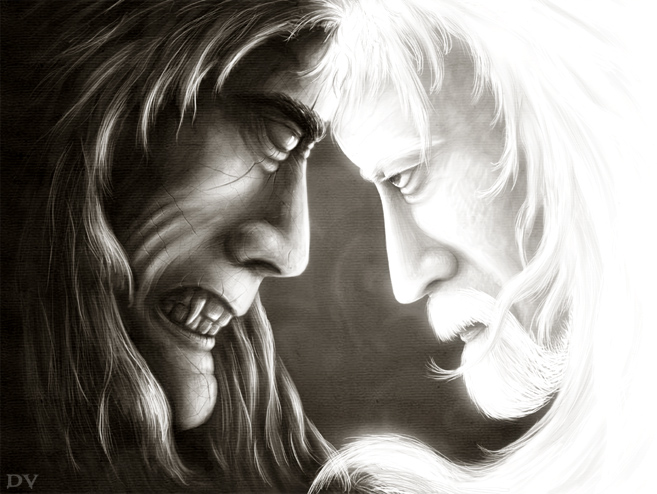

Even in ancient Iran the mythological worldview was built on the opposition of the forces of Good and Light, embodied in the ethical law Arta and personified by the great Ahura Mazda — “Lord of Wisdom,” “Wise Lord” (Greek: Ormuzd) — and the forces of Darkness and Evil, embodied in falsehood and personified by Angra Mainyu (Ahriman).

This dualism spread widely through the East and later passed into the ancient and medieval worlds. Mazdaism did not immediately become the state religion of Iran. When Cyrus the Achaemenid (558–529) founded his realm, he practised religious tolerance, but gradually the gods of Iran were displaced by the cult of Ahura Mazda.

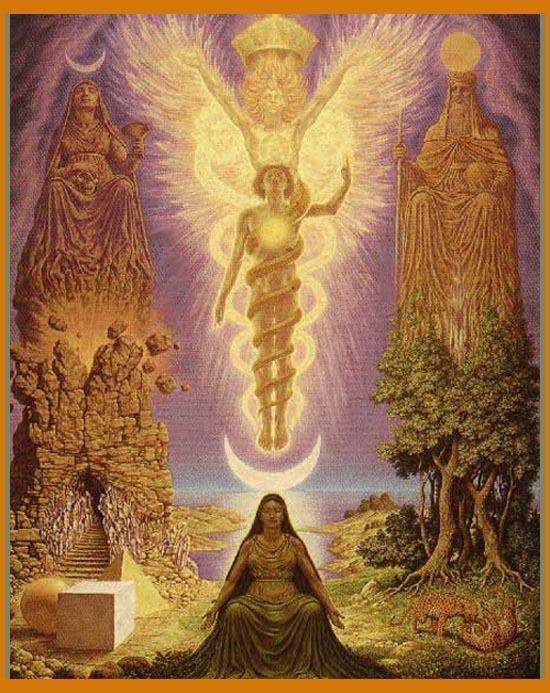

According to ancient Iranian conceptions, on the cosmological level the first creation belonged to a principle higher than the light-dark duality — Zervan Aion (Infinite Time). In a purely symbolic sense he embodies the cycles of time — applying not only to the historical epochs of the world’s existence but also to the life-death transformations to which all living beings are subject. As Zervan-Akarana (Infinite Time) he represents time as fate, law, and inevitability. In some Iranian schools the dualism was developed to such an extent that Zervan’s role as a supreme deity was reinterpreted and supplemented. The result was the magical concept of Azrvan Akarana — a synthesis that, while ‘beyond good and evil,’ still conceives of Zervan as a purely creative god of time combined with the feminine but destructive energy Az, later reflected by the Aramaeans who adopted the legend as Ru’ha or, in anthropomorphic form, Lilith.

The most esoteric Iranian traditions explain that evil existed before the world’s creation. Zervan, as the Supreme God, performed sacrifices for a thousand years to obtain offspring, and when hope was nearly lost two sons finally appeared — Ahriman, the fruit of his doubt, and Ormuzd, the fruit of his faith. Ahriman saw the light before Ormuzd, but the latter was destined to triumph, albeit not without struggle.

The second stage of Creation — the making of the human world — aimed at defeating evil. The cosmic process was viewed as the struggle of eternal good and evil, or of Truth (Arta) and its opposite — Lie (Drauga, Druj). The benevolent part of the earthly world was created by the good principle; in response the evil spirit produced a countercreation, bringing death, winter, heat, harmful animals, and so on; the constant struggle of the two principles determines all existence in the world.

The original divine duality was mirrored in a similar duality among humans. Even before creation, two twin spirits made a choice between good and evil (which determined one as holy and the other as hostile). A similar choice was then made by the Amarta Spentas, who took the side of good, and by the daimons, the herd (“the soul of the bull“), who chose evil. The same choice is offered to man.

In the middle of the 1st century CE, on the northwest shore of the Dead Sea in the Engedi region, there lived a secluded sect that had withdrawn from the world, rejected marriage and family life, and were “unfamiliar with money” — that is, they evidently earned their living by communal labour — the Essenes. The name they chose for themselves, “Essenes,” derives from the Syriac word Asaya, meaning “physicians,” and in Greek “therapeutae.” Their public activity consisted in healing physical and moral ailments. They lived on communal principles, i.e., in a commune.

Pliny’s remark that the Essene community received “strangers wearied by life” is also striking. In seeking social causes for the emergence and long historical existence of the Essenes, Pliny finds in the desire to separate from society people who were disappointed with their lives or with the social system and its spiritual values. At the same time he expresses surprise at the size of this group and at their ability to sustain themselves across generations.

The Essenes practised communal ownership, stood out for exceptional piety and moral purity, and valued celibacy above marriage. Moral values occupied the central place in Essene life; they avoided oaths and did not attribute great importance to sacrifices. Although they zealously observed rites, their goal appears to have been spiritual perfection.

They devoted much attention to preaching, to physical and spiritual purity, to washings and other hygienic practices, which they considered connected with spiritual life. The “creed” of the Essenes begins with the following words: “From the all‑knowing God of all that is and has been… He created man to rule over the world and placed within him two spirits, to guide him until the time appointed by him. These are the spirits of Truth and of Kriwda. In the hall of light is the genealogy of Truth, and from the springs of darkness the genealogy of Kriwda” (3,15 el.). Thus their ideas were likewise dualistic.

The three pillars of Kriwda, or Belial, were named intemperance, wealth, and lawlessness. The servants of Kriwda are rapists and oppressors, corrupt and greedy people who trample their fellows without law. Truth, by contrast, stands on asceticism, non-possession and reverence before the Being. Its spirit is “the spirit of humility, long-suffering, great mercy, eternal good, intelligence, understanding and mighty wisdom, which inspires faith in all the deeds of God.”

The way of man, the Essenes believed, is predestined before his birth. “Servants of Kriwda” will remain such for ever, while only the “elect” will be saved, who should joyfully await the destruction of the “sons of darkness.” Moreover, the Essenes believed that they would take part in the world battle that angels would wage against pagans and Jews who did not accept the Essene doctrines.

After the spread of Christianity at the very beginning of the Christian era, in the 1st century CE a complex of religious‑philosophical schools developed in the Near East or in Alexandria, called the “Gnostics” (from “gnosis” — knowledge). As such, the gnostic movement appeared in the pagan world before Christianity, and it also existed simultaneously and parallel to Christianity, interacting with it, suffering its influence and influencing it in turn, giving rise to a distinct Christian gnosticism. Gnosticism is characterized by two myths, in most cases corresponding to dualism and based on the existence of a demiurge (“the artisan god” who created the world, as opposed to the Creator). The first is the myth of a female trickster, the heavenly goddess Sophia, whose action brought about a catastrophe resulting in the creation of the world. The second is the myth of a male trickster, an illegitimate offspring of Sophia, who created the world either from impure matter called water, or from refuse or thoughts that came to him from above from the true God. As a rule, in gnosticism the Demiurge is identified with the God of the Old Testament. The gnostic Demiurge has nothing in common with the Demiurge of Plato’s Timaeus, who is conceived as unambiguously good and forms the visible world according to a divine archetype. According to the gnostics, the Highest God dwells in the heavens, but out of compassion for humanity he sends to people his messenger (or messengers) to instruct them how to free themselves from the power of the Demiurge.

With such a view, the world itself — material existence in all its forms — at best constitutes a lower state, and at worst is evil, and the same applies to the God who created this world. For gnostics, the sensible world is the result of a tragic mistake in the Absolute, or of an invasion of the forces of darkness into the worlds of light. The Unborn Father reveals himself in special entities — aeons (sephiroth in Kabbalah), often forming pairs. The completeness of these aeons forms the divine fullness — the Pleroma. The pride of one of the aeons leads to its fall from the Pleroma and to the beginning of cosmogenesis, the lowest of the ensuing worlds being our material world. The universe is the domain of the Archons, who are often called by names of God from the Old Testament (Sabaoth, Adonai, etc.). Around the world lie cosmic spheres, like concentric shells, the number of which varies from 7 (most common) to 365 in the system of Basilides. The religious significance of this architecture lies in the infinite remoteness of man from God, expressed here by the multitude of aeons inhabited by demonic archons, whose tyrannical rule is called “Heimarmene” (cosmic fate). As guardian of his sphere each archon bars the way to souls returning to God after death. The chief role in the creation of the world belongs to the head of the archons — the Demiurge.

The teachings of various gnostic schools found expression in an extremely extensive corpus of writings, but most of these works were destroyed as heretical. The best known founders of gnostic sects were Simon the Magus, Menander, Saturninus, Cerinthus (1st century CE), Basilides (d. c. 140), Valentinus (mid-2nd century) and Marcion (2nd century), each of whom had his own gnostic system.

In the 4th century a movement of the Manichaeans appeared in the Roman Empire, founded on a dualistic worldview and close to gnostic teachings. The name of this movement comes from its founder — the semi‑legendary Mani (c. 216–276). He was born in Ctesiphon (Persia) into a family of sectarians called the “baptizers,” who were attached to the gnostic communities of the Mandaeans. By virtue of this, Mani became acquainted with esoteric doctrines. For a time he served as a Christian presbyter. Drawing in small part from different sources, he developed his own Christian‑gnostic doctrine. Manichaeism is unquestionably a syncretic religion, as Mani himself states. It includes Zoroastrian (principial), Christian (Jesus as saviour) and Buddhist (ascetic morality, doctrine of transmigration) elements. “The basis of Mani’s teaching consists in the infinity of the first principles (Light and Darkness), the middle part concerns their mixture, and the end — the separation of Light from Darkness.”

Mani’s teaching is pessimistic, since it posits the idea of the primordiality and irreversibility of evil, which is as autonomous and ancient a principle as good. Associating evil with matter and good with light and spirit, Mani nevertheless did not see darkness or matter as the consequence of the fading of light; in Manichaeism the kingdom of darkness stands as an equal adversary to the kingdom of light. World history is the struggle of light and darkness, good and evil, God and the devil. Man is dual: a creation of the devil, he is nevertheless fashioned on the model of the heavenly “luminous primal man.” According to Mani, the Gospel Christ was a false Christ. The true Christ did not incarnate and did not unite the natures of God and man. After Christ, Mani was sent as the Paraclete (Comforter) — the chief of the messengers of the Kingdom of Light. Fundamental principles of Manichaeism are: guarding the soul from all bodily defilement, self-denial and restraint, the gradual overcoming of the fetters of matter and the final liberation of the Divine essence imprisoned in man. The Manichaeans were expelled from Ctesiphon and scattered to neighbouring territories. The Manichaean “patriarch” Sissinius, recognised after a brief internal struggle within the sect, settled in Babylon, forsaken by gods and authorities. Some Manichaeans fled beyond the Oxus (Amu Darya) and in the 5th century proclaimed their autonomy from the Babylonian patriarch; this autonomy lasted until the 8th century, when the Manichaean communities of Central Asia recognised the supreme authority of Babylon.

The further spread of Manichaeism occurred through its disciples, who passed the founder’s teaching to their successors along a long hereditary chain — centres of Manichaeism cropped up in many different states and many of them remained cut off from the homeland, functioning as autonomous cults. The ideas that Mani implanted at the founding and subsequent development of his teaching were so well balanced that they changed little over time and were able to supplant many native religions.

During the 4th century Manichaeism spread throughout the Roman Empire — from Egypt to Rome, southern Gaul and Spain. Both the Christian Church and the Roman state subjected Manichaean communities to brutal persecutions. Emperor Diocletian, by decree in 296, ordered the proconsul of Africa to persecute the Manichaeans in order to “root out with branch and root” the “abominable and impious teaching” that had come from Persia. Their leaders and preachers were to be burned with their books, the clergy to be beheaded, and the followers to be sent to hard labour with confiscation of property. This decree was provoked by a complaint of the proconsul to the emperor that the Manichaeans were causing disturbances and disorder in the cities. Theodosius I, by edict of 381, deprived the Manichaeans of civil rights, and the following year prescribed the death penalty for professing this religion. Valentinian II sent the remaining Manichaeans into exile (naturally with confiscation of property). Honorius in 405 confirmed all the edicts of his predecessors and again declared the Manichaeans outlawed. Valentinian III, Anastasius, Justin and Justinian did the same, the latter not only with regard to the Manichaeans but also to those who had apostatized yet continued contacts with their former co-religionists. Thus, by the end of the 5th century pure Manichaeism had completely disappeared from the territory of Western Europe, and by the 6th century from Eastern Europe as well.

Among the movements following the Manichaeans were the Paulicians and the Bogomils. The Paulicians distinguished the Good God, or Heavenly Father, revealed in Christianity, from the demiurge who created the visible world and human bodies. The fall of the first man was understood as disobedience to the demiurge and consequently as liberation from his power and revelation to the Heavenly Father. The Paulicians regarded Christ docetically, asserting that he was not a man but only a phantom who passed through the Virgin Mary as through a channel, with the aim of destroying the cult of Satan. The Holy Spirit is invisibly conveyed only to the truly faithful, to the Paulicians. The Paulicians preached radical dualism, denying any ritual, ceremonies, cult buildings, icons, the cross and the sign of the cross, saints, sacraments, church hierarchy, fasts, asceticism and monasticism. Of all the sacraments they retained only baptism and the Eucharist, which were performed in a non-material, spiritual way. Worship consisted exclusively of teaching and prayer. The leaders of the school took the title “Disciples of the Apostles” and assumed the names of real apostolic disciples.

In Bogomilism the two principles — good and evil — are not regarded as independent, but as subject to a higher good being. According to the Bogomils’ teaching, God originally had a first‑born son, Satanael, who was second only to God and ruled over all angels. Proud of his power, Satanael resolved to become independent of the Father and was cast down from heaven. There, too, Satanael resolved to build his independent kingdom. Possessing divine creative power, he created from the chaos a new heaven and earth and fashioned Adam, into whom he vainly tried to breathe a living soul. Turning to God the Father, Satanael asked him to blow into the first man a soul and bring him to life. He intended that after this he would rule over the bodily part of man, while the Father would rule over the spiritual, with human spirituality replacing God for the angels who had fallen with Satanael. Eve was created in the same way. But Satanael envied men, who were destined to take the place of the fallen angels, and decided to subjugate the human race. Entering the serpent, he seduced Eve and begot Cain and his sister Kalomena from her, hoping that his offspring would prevail over Adam’s. Thus Satanael was able to subdue the whole human race, and only a few men remembered the original purpose of humanity — to replace the fallen angels. In their forgetfulness people took Satanael himself for the Supreme God, and Moses, being Satanael’s instrument, especially propagated this belief. In the 5,500th year from the creation of the world God decided to free men from Satanael’s power and produced a second son, Jesus, or the Word, whom the Bogomils also called Michael. The incarnation, life and death of Jesus the Bogomils understood docetically. Jesus came into the world in an ethereal body resembling a human one and passed through the Virgin Mary unnoticed, so that she did not understand how she found him a child in a cave. Satanael, striving to undermine Jesus’ influence on men, brought him to a death that was also illusory. Yet three days after his death Jesus appeared to Satanael in his divine form, bound him in chains and stripped from his name the final divine syllable “-il,” after which he became simply Satana. Then Jesus ascended to heaven and became second after God, head of all the Angels. To complete his work on earth the Father produced another power, the Holy Spirit, which acts directly upon human souls. The souls of the Bogomils, feeling the action of the Holy Spirit and communicating this action to other souls, are true godbearers. Such people do not die but cast off the body and migrate to the kingdom of God. When the Holy Spirit completes its work and all souls have migrated to the kingdom of God, all matter will turn to chaos and Jesus and the Holy Spirit will return to the Father from whom they came.

The Cathars (from the Greek for “pure”), or Albigenses (from “albus” — “white”), arose in Occitania (southern France) on the basis of a numerous “heretical” movement among commoners and nobility. The Cathars spread in the 11th–14th centuries in northern Italy and France. They believed that the earthly world, the Catholic Church and secular authority were created by Satan, and they declared the Roman Pope to be the vicar of the devil. The Cathars adhered to a dualistic doctrine akin to Manichaeism, positing two principles — a good one in the form of God and an evil one in the form of the devil. They denied the dogmas of Christ’s death and resurrection, rejected the cross, churches and icons. The Cathars declared the seven Christian sacraments a diabolical deception and practised public confession once a month at a community assembly. The Eucharist was replaced by the blessing of bread, performed daily at a common table. Baptism by water was replaced by a spiritual baptism effected through the laying on of hands and an apocryphal Gospel of John upon the baptized. Fearing that a priest’s hands might be defiled by sin, baptism was often performed two or three times. The Cathars rejected marriage, though they did not force family members joining the community to dissolve their unions. Marriages were occasionally permitted between young people on the strict condition that they remain chaste until marriage and cease sexual life immediately after the birth of the first child. Some Cathars forbade marriage only for the “perfect,” but they uniformly regarded sexual life as an expression of original sin by which Satan continued to maintain his power over men.

The last and bloodiest stage in the history of the Cathars was the series of battles (1209–1228), often called the Albigensian Wars or the crusades against the Albigenses. Particularly fierce were the battles at Béziers, Carcassonne, Lavaur and Muret; the forces were led by the Count of Toulouse (on the side of the sectarians) and Simon de Montfort (on the side of the crusaders). Even before this, in 1208, Pope Innocent III called for a crusade after the sectarians murdered a papal legate. Under the peace treaty of 1229 at Meaux (the Treaty of Paris), much of the Albigensian territory passed to the King of France. Dispersed remnants of the sect, however, survived until the end of the 14th century.

For more than thirty years popes and French kings waged a bitter struggle against Cathar “heresy.” Yet curiously the most powerful and militant order of crusading knights — the Order of the Temple (the Templars) — remained aloof from the campaigns in Languedoc throughout these years. In response to the pope’s call to take part in the war against the Cathars, the Templar leaders explicitly stated that they did not regard the French invasion of the County of Toulouse as a “true” crusade and did not intend to participate.

The Albigensian campaigns and the persecution of the Cathars increased Cathar influence among the Templars. As early as 1139 Pope Innocent II, a patron of the crusaders, granted the Order of the Temple numerous liberties and privileges, among them the right to accept into the brotherhood knights excommunicated for sacrilege, heresy, blasphemy and murder. This right allowed the Templars to shelter those excommunicated knights who were persecuted, bringing them into their ranks. Particularly many Cathars joined the Order after 1244, when the Albigensians suffered final defeat and spies of the Holy Inquisition and the French crown roamed all over southern France searching for heretics.

Always and everywhere gnostics were anathematized, tortured and burned; yet the fascination of these views was too strong, and in the form of various schools and movements they have survived to the present day.

Ermenkar, does it turn out that all kinds of movements like Jehovah’s Witnesses, Pentecostals, Baptists, etc. are all echoes of Gnostic movements and just a mosaic of positions they liked the most?