Reincarnations or the Transmigration of Souls

Unlike the southern branch of Indo‑European civilization, belief in obligatory reincarnation was not universal among its northern and western peoples.

At the same time, not only the ancient Greeks (for example, the Pythagoreans) but also the Celts acknowledged that the same personality could inhabit different bodies in different forms.

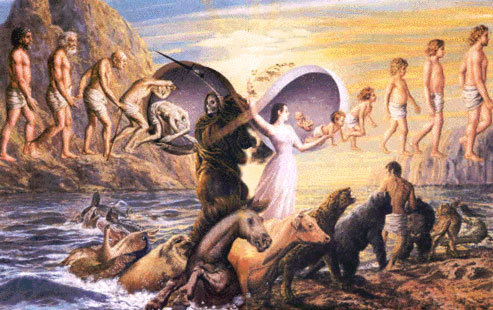

An example is the Irish legend of Fintan (Tuan), one of the first settlers of Ireland, who arrived there before the Flood and, having lived on in many human and animal bodies, survived into the Christian era.

Caesar’s remark is well known in The Gallic War, an invaluable source for Celtic ethnography, where he describes the teaching of the druids thus:

“Among other things the druids endeavor to instill the conviction that souls are not subject to destruction, but after the death of one being pass into another; the aim of this teaching is to instill contempt for death and to make [men] braver…”.

In the saga “The Birth of Cuchulainn,” it is told how the warriors of the king of Ulster found, by a miracle, a woman in labour; the boy she bore was taken into the court and brought up by the king’s daughter Dechtire until he grew up. Then a disease attacked him and he died. After three days of mourning for her foster‑child, Dechtire was seized by a thirst. In the cup that was brought to her she saw a tiny creature which tried to jump into her mouth. She tried to blow it away and then drank the cup, and the little creature “slipped and crept into her.” In a dream Dechtire was visited by a man who said to her: “I took on the form of the boy who was born there, and you reared me; they bewailed me in Emain Macha when the boy died. But now I have returned again, having entered your body in the form of that little creature in the drink. I am Lugh of the Long Arm, son of Ethliu, and from me a son will be born, now enclosed within you. His name will be Setanta.” After this Dechtire became pregnant, and however she strove to rid herself of the fetus, the child was born, grew up, and in time was named Cuchulainn, becoming the greatest hero.

The examples above show that the Western European notion of the transmigration of souls differs markedly both from the Indian and the Pythagorean.

According to Porphyry (V Pyth. 19):

“What Pythagoras taught his disciples no one can say with certainty, for they took a strict vow of silence. Of his teachings, the following are the most widely known: that, according to him, the soul is immortal but passes into other living beings… “

The Celtic conception of transmigration, however, did not concern all beings. It applied only to certain heroes, who returned to the world of the living again to fulfill their mission.

The Scandinavians were also familiar with the idea of reincarnation.

In an old Norwegian saga, it is recounted how King Olaf the Holy (995–1092) once rode with his warriors past a barrow where the renowned konungr Olaf Alv Geirstadira was buried. Someone of the retinue asked King Olaf: “Tell me, sovereign, are you the one who is buried here?” The king answers him: “My spirit has never had two bodies and never will — neither now nor on the day of resurrection. And if ever I answered otherwise, then there was no true faith in me.” To this a man of the retinue says: “Among the people, it is told that, being once at this place, you are said to have said: ‘Here I was and here I rode’.” The king answers: “I never spoke such nonsense; I could not have said anything like that.” And, becoming greatly agitated, he spurred his horse and hurried away.”

The author of the songs about Helgi Hunding’s Slayer at the end of the second lay remarks: in the old days people believed that men are born again (“trua i forneskio”), but now that ancient belief is regarded as old wives’ tales (“ker-lingavilla”).

There are also accounts of Slavic conceptions of reincarnation.

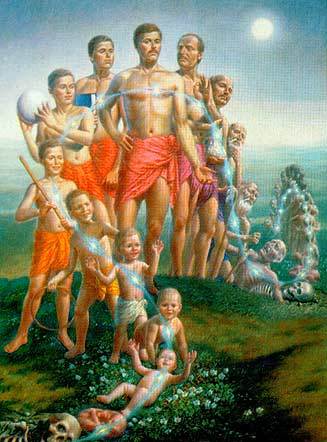

It is believed that the widespread ancient practice of crouched burials imitated the fetal posture in the mother’s womb; the crouched position was achieved by binding of the corpse. Relatives prepared the deceased for rebirth on earth, for his reincarnation as a living being.

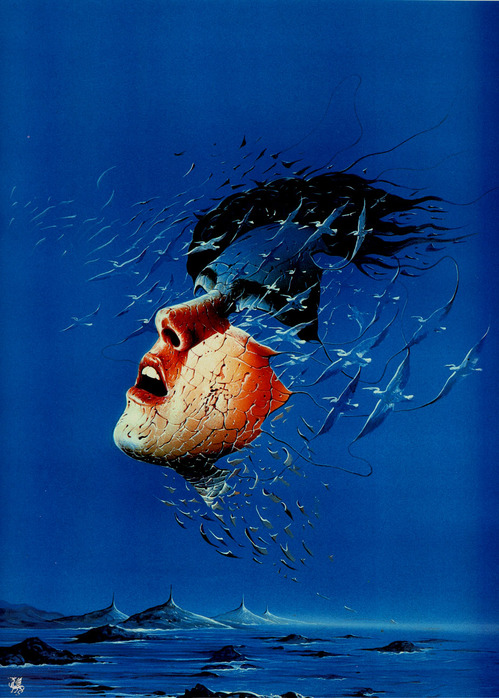

When a person died, according to the beliefs of the ancient Slavs, his soul, or spirit, departed the body like “a little wisp of smoke.” The fate of these spirits, in ancient belief, varied. Some of them remained on earth, doing good or harm; others went to heaven, continuing to influence the lives of their descendants. It was also thought that the souls of the dead sought refuge in animals or objects, so many healing practices were associated with animals: for a headache a puppy was placed on the forehead, for fever a goat was tied nearby, etc.

At the same time, the most essential question remains the intermittent manifestation, the disappearance of personality.

Adherents of “obligatory” reincarnation explain this by special transformations that accompany the transmigration of souls and lead to loss of memory.

Thus, we see that the idea of obligatory reincarnation is one consequence of belief in the immortality of the soul as the carrier of personality.

The failure of personality to persist is precisely what prevents a direct connection between incarnations.

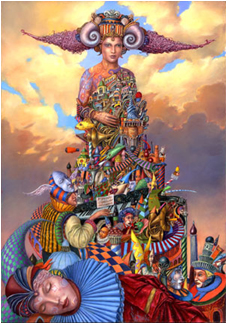

The European pagan conception of transmigration was deeper than modern primitive notions of the process. What was meant was precisely transmigration, the flowing of a special invisible and imperceptible substance, a life‑force, which produced the fact that two lives of completely different personalities somehow became connected to one another and tinged with the same tone.

Most accurately this could be expressed in words such as “A. contains the same spirit as B.” — that is, A. and B. are linked by the presence in each of some common component, not a “soul” which is formed during life, but rather an elusive constituent, a kind of “seed particle,” the presence of which alone makes it possible to speak of continuity between incarnations.

The idea of the transmigration of souls is elaborated in great detail in the Kabbalah. One such teacher — Simon Magus — describes his previous lives. His soul passed through many bodies before it reached the body known as Simon. Also known is the Samaritan teaching of tahebe, which contains the same doctrine of the soul’s preexistence given to Adam, which, through successful incarnations in Seth, Noah, and Abraham, reached Moses, for whom it was originally created and for whose sake the world was made.

The famous disciple of Isaac Luria, Rabbi Chaim Vital Kalibres, an Italian kabbalist of the sixteenth century, provided the world with the most detailed written documents on reincarnation in the Jewish mystical tradition. In particular, his work “Sefer (or Sha’ar) HaGilgulim,” meaning “Gates of Reincarnation,” is undoubtedly one of the greatest Jewish literary monuments ever written on this subject:

“Know then, the reason the sages of our time are overcome by their wives is the circumstance that these holy men are the reincarnated souls of the generation of the Exodus, especially those among them who did not try to prevent the dissenters from making the Golden Calf. The women of that time, however, refrained from participating in this and refused to give their jewels to the makers of the Golden Calf. Therefore now these women prevail over their husbands.”

Medieval Kabbalists distinguished three types of reincarnation: gilgul, Ibbur, and Dibbuk.

Gilgul corresponds to what is usually called reincarnation: the soul enters the embryonic fetus during pregnancy.

According to the Electronic Jewish Encyclopedia, the belief in the transmigration of souls characteristic of many religions and philosophical systems of the ancient world was apparently foreign to Judaism until the end of the Talmudic era, where it is not mentioned.

The “Zohar,” one of the classical kabbalistic texts, teaches that the place to which each goes after death depends largely on a man’s inclinations in life and his last thoughts immediately before death:

“The way a person chooses in this world determines the further path of the soul after its departure. Thus, if a man is drawn to the Sacred and strives toward It in this world, then the departing soul is borne upward to the higher realms by that inertia of movement which it acquired each day in this world.”

Most early kabbalists did not regard gilgul as a universal law but rather as a severe punishment. At the same time, gilgul can be an expression of the Creator’s mercy, “for the Lord does not abandon forever“: even a soul deserving complete annihilation can be reborn by means of gilgul.

Anan ben David, who in the eighth century founded Karaism, an important Jewish sect, openly professed his belief in reincarnation and, despite his sect being considered heretical for rejecting the Talmud, he was nonetheless a respected Jewish thinker of his time. Abraham bar Hiyya of Spain, the foremost kabbalistic figure from the twelfth century on, taught that the soul is born again and again until it attains perfection. Many early kabbalists held that the sacred Jewish scriptures definitely support reincarnation, where it is said that one who does not observe strictly the 613 commandments of the Torah cannot secure his place in the world to come that will replace this one:

“If a man has not perfected himself in the observance of all 613 commandments — in deeds, speech, and thoughts — he will inevitably become the object of gilgul [reincarnation]… Furthermore, the soul of everyone who has not studied the Torah according to the four levels [of understanding], expressed by the word prds, which consists of the first letters of four words: peshat (‘literal’), remez (‘allegorical’), derash (‘homiletical’), and sod (‘secret’ or ‘mystical’) — that soul will return for reincarnation, so that he may fulfill his purpose and come to know each of these aspects…”.

Having accepted the doctrine of gilgul (especially after the appearance of the Zohar) as one of the main tenets of the Kabbalah, its proponents sharply disagreed on details. The “Sefer ha‑Bahir” (“The Bright Book”) asserts that gilgul may continue for a thousand generations, but most early Spanish kabbalists held a different view. The words “… God does this to a man two or three times” were interpreted by them as indicating that a sinful soul is reincarnated three times before achieving redemption; the souls of the pious, however, undergo an endless process of transmigration, not for their personal benefit but for the good of humanity. Another school held the opposite: the soul of the righteous transmigrates only three times, while the soul of the sinner a thousand times.

Later, gilgul ceased to be seen as punishment for sin and was proclaimed a universal principle, from which arose the belief in the transmigration of a human soul into the body of an animal, into a plant, and even into inanimate substance. A comprehensive development of the concept of gilgul is found in the works of Yosef ben Shalom Ashkenazi (early 14th c.) and his colleagues. In their view, everything that exists — from the emanations of the Most High (see Sefirot) and the angels down to inanimate matter — is subject to constant metamorphosis, whereby the highest forms of being descend into the lowest matter, and having embodied there they again ascend to their exalted source.

The doctrine of gilgul is linked to the concept of Ibbur (the notion of the inhabitation of an alien spirit in a person), which arose in the second half of the thirteenth century. Ibbur, unlike gilgul, does not occur during the period when the embryo is in the mother’s womb or at the time of birth, but at some moment in a person’s conscious life. A soul that enters a person’s body by way of Ibbur dwells there for a limited time and only in order to urge him to certain deeds or to accomplish a known mission. The concept of Ibbur later developed into the idea of the Dibbuk.

Ibbur (“impregnation” or “grafting”) occurs when a “foreign” soul enters someone’s body during that person’s life and remains there for some time to achieve a certain aim. When such a soul enters a person’s body with malevolent intent, the invading soul is called a Dibbuk. Dibbuk (literally “attachment“) is an evil spirit that enters a person, takes possession of his soul, causes spiritual affliction, speaks through the victim’s mouth, but does not merge with him, retaining its independence.

It is believed that the spirits called Dibbuk are transmigrating souls that cannot enter a new bodily form because of their past sins and therefore are forced to inhabit the bodies of the living. Moreover, these spirits were compelled to enter human physical shells lest they be tormented by other evil spirits. Some held that Dibbukim are the souls of those not given proper burial and hence turned into demons.

Tales of the inhabitation of an evil spirit were widespread in the period of the Second Temple. They occur frequently in Talmudic and Midrashic literature; they are reflected in the Gospels as beliefs current at the time of the birth of Christianity. From such stories and the thirteenth‑century teaching of temporary inhabitation of an evil spirit in a person’s body (Ibbur), which merged in popular consciousness with the doctrine of the transmigration of souls and with the widespread folk notion that the souls of the unburied become demons, the belief in the Dibbuk was formed.

Although the term Dibbuk appeared in Jewish literature only in the seventeenth century, reports in Hebrew and Yiddish of the expulsion of a Dibbuk are known from 1560. The Dibbuk was regarded as a soul that had lost the ability to reincarnate because of the burden of its sins. Being a “naked soul,” the Dibbuk seeks shelter in the bodies of the living. According to belief, a Dibbuk enters the body of a person who has committed a secret sin. The writings of some kabbalists, students of Isaac Luria, contain detailed instructions on the expulsion of a Dibbuk.

It was believed that specially prepared rabbis (ba‘al‑shem) and other holy men (tzaddikim) possessed the ability to expel a Dibbuk from the possessed, giving it an exit either through rectification (tikkun), which opened the way to gilgul, or by casting the Dibbuk down into hell. Exorcisms of Dibbukim were still performed in the early twentieth century. In 1903, spirits of the false messiah Sabbatai Zevi and his prophet Nathan of Gaza were expelled in Baghdad. The last documented exorcism of a Dibbuk was recorded in Jerusalem in 1904.

As a rule, a Dibbuk leaves the body of its victim through the little toe, where a tiny bleeding sore appears. It is by the presence of this sore that one can determine whether the spirit has departed or not.

It is clear that the last two types are more a matter of possession than of reincarnation.

Thus, we see that the idea of the transmigration of souls was a characteristic concept of various mythological systems, although its semantic, ideological, and consequently practical significance varied greatly.

In the Kabbalistic tradition, the existence of the soul is an analogous process to the Existence of the Absolute, taking place, however, in a sequential form. The Absolute realizes itself in infinite potentials, and those, in turn, realize themselves in successive incarnations. Achieving completeness of realization at the level of Monads is the Higher Kingdom in which souls await the end of this world.

Reincarnation is a natural course of events for the Monad but not for the embodied person. For him, each life is the first and the last, and only through development can he reach a level of consciousness not subject to decay, thus becoming aware of/remembering his previous reincarnations. It is also believed that once reached, this awareness will be much easier to regain in subsequent reincarnations if they are needed.

There are also interesting differences in the methods of “helping in transitions”; some traditions sought to preserve the body (hiding it under the protection of the element of Earth), considering it a pledge of the afterlife, while others destroyed it in the fastest way using the elements of Fire and, in some cases, Air. Some aimed at purification before death, renouncing possessions and various “debts”, presumably believing that attachments would complicate the transition, while others, on the contrary, sought to take everything binded them together.

In the same Celtic mythology, these approaches are combined… along with examples of reincarnations, the gods of Tuatha De Danann also transitioned to the otherness and lived (and still live today) in personal sidhe (barrows).

Thank you for the luxurious information; you advanced my searches… Good luck and more articles…

Thank you for the material! It was very interesting. I was surprised to find the similarity between kabbalistic notions of the rebirth of souls and the interpretation of this process by R. Monroe in his second book “Far Journeys.”

But a question arises: there are currently 6 billion people on earth, and there were once much fewer, and perhaps there will be much more – If souls are constantly incarnating and disincarnating, then there is some strictly defined number of these souls and they wait in line somewhere in the stream or as the world expands, are new souls created by someone or something (the number of living beings on earth increases) which, for example, come into the world for the first time?

Thank you, Love from Bulgaria Regarding the number of souls and people – where does the information come from, and can it be considered reliable?