Kabbalah before Kabbalah

Questions about the antiquity and origins of Kabbalah are resolved in different ways depending on one’s aims. As mentioned, some regard Kabbalah as old as the world, while others see it as a late-medieval product. Everything depends on the standpoint: what we consider when the teaching originated — its modern form or the ideas that underlie it.

Modern Kabbalistic tradition is reasonably considered to have been formed in the 12th–13th centuries, although according to Kabbalah’s own accounts, the oral tradition was formed much earlier. The word “Kabbalah,” that is, “tradition,” appeared very early and was widely used by Talmudic teachers, where the term designated parts of the Bible not included in the Pentateuch, and in the post-Talmudic era, the Oral Law. Only in the 12th century did Jewish mystics begin to use it to emphasize their teaching’s continuity with the esoteric wisdom of the past.

One of the first and most important works that laid the foundations of kabbalistic doctrine is considered the “Book of Creation” (Sefer Yetzirah), written, according to some accounts, between the 2nd and 6th centuries CE, and according to others in the 8th–9th centuries.

The flowering of Jewish Kabbalah was spurred by the book the “Zohar” (“Radiance” or “Splendor”), most likely composed in the 13th century. Kabbalists assert that the book was written by Rabbi Shimon bar Yochai (RASHBI) in the 2nd century CE and was kept hidden for many centuries. The Zohar contains, in one form or another, most of the kabbalistic theories with which its author appears to have been familiar.

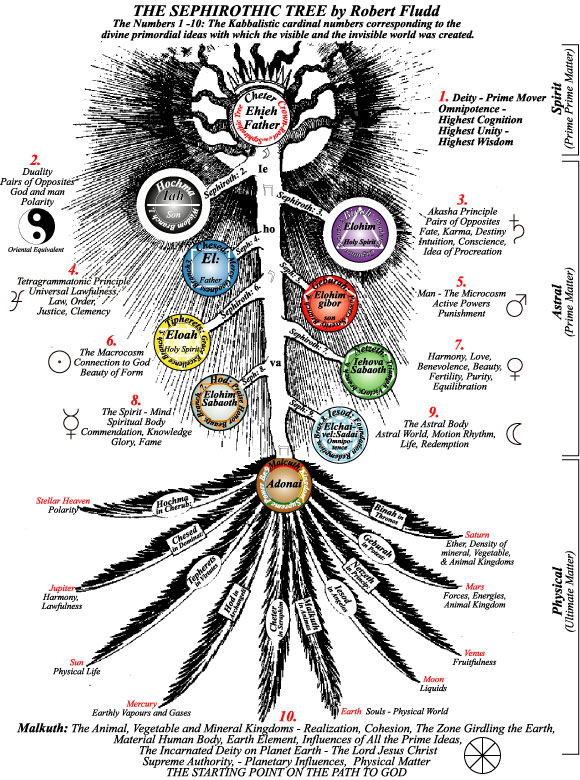

However, it was Isaac Luria (1534–1572) who gave Kabbalah renewed vitality. The school of Lurianic Kabbalah bears his name. As a result of Luria’s work, Kabbalah transformed from descriptions of mystical experiences — the trials of passing through various halls of the heavenly palaces (hechalot), guarded by angelic hosts, on the way to the Throne of Glory — into a coherent system to describe the world’s order. It is to Luria that we owe the formulation of the concept of the Tree of Life in the form in which it is known today. Developing the concepts of the 10 sephirot, Luria advanced the ideas of tzimtzum, shvirat kelim, and the origin of evil in the Qliphoth.

In the European variant, Kabbalah incorporated Pythagorean numerology, European shamanic and pagan traditions, Hermeticism, and Sufi mysticism, did not conflict with Christianity, and was sometimes seen as part of Catholic thought. The penetration of Kabbalah into Europe is usually associated with the book “Potae Lucis” (“Gates of Light”), published in 1516, which contained a Latin translation of the kabbalistic work “Sha’arei Orach,” written around 1290 by Rabbi Joseph Gikatilla (1248–1323).

By the end of the 13th century, the so-called “Christian Kabbalah” had already emerged, its earliest representatives being Abner of Burgos (c. 1270–1346) and Paulus de Gheredia (c. 1405–1486). The center of this movement became the Platonic Academy in Florence, created in the second half of the 15th century by the Florentine aristocrat Cosimo de’ Medici. Its main figures were the well-known Neoplatonic philosopher Marsilio Ficino (1433–1499), who translated the corpus of Plato, Plotinus, and some Neoplatonic and Hermetic texts from Greek into Latin, and his pupil Pico della Mirandola (1463–1494), the father of Christian Kabbalah.

However, Kabbalah is not entirely original, although many elements borrowed from Jewish and non-Jewish sources were altered beyond recognition or received new interpretation. The formation of Kabbalah was influenced above all by gnosticism and Neoplatonism, although that influence is not always obvious and manifests differently in various kabbalistic currents. The widespread Cathar movement in the 12th century in southern France probably had a significant influence there; their gnostic-Manichaean teaching contained elements that later became characteristic of Kabbalah: esotericism, dualism, symbolic thinking, and so on.

The idea of “emanation” borrowed from Neoplatonism acquired in Kabbalah the form of a doctrine about the origin of a series of Divine entities — the ten sephirot — from the infinite, unlimited Divine substance (Ein Sof), to which no attributes can be ascribed. The “limiters” of the Divine Light — the sephirot — are in constant dynamic interaction and govern the material world, thereby creating a continuous chain of creation. But whereas in Neoplatonism emanation is an involuntary process, Kabbalah sees it as a volitional act of God, concealed within His being. Associated with the notion of emanation in Neoplatonism is the symbolism of light, which was also adopted by Kabbalah. Images of a torch, a burning candle, or the sun, that emit light and often symbolize God and the ten sephirot in Kabbalah, are distinctly Neoplatonic in character.

As early as the 16th century, Agrippa of Nettesheim noted the affinity between Kabbalah and gnostic doctrines. And in the 20th century, the foremost scholar of Jewish mystical teaching, G. Scholem, declared: “Kabbalah in its historical meaning can be defined as the product of the interpenetration of Jewish gnosticism and Neoplatonism.” It is hard to say which is primary, but the parallels between kabbalistic and gnostic worldviews are undeniable.

The mysticism of the Divine Chariot (Merkavah) represents such an obvious parallel to Gnosticism within the Jewish esoteric tradition that it is even called “rabbinic Jewish Gnosticism.” A gnostic element of Kabbalah is also the dualism in the conception of the Divine, although in Kabbalah this dualism takes a moderated form.

Kabbalah distinguishes two Divine principles: the boundless, absolutely attributeless, and incomprehensible (Ein Sof), and the Creator who is accessible to comprehension (sephirot). But unlike non-Jewish gnosticism, which perceived the demiurge as an embodiment of evil ruling over the world it created, Kabbalah, in accordance with the traditional outlook of Judaism, regards the world as the best of possible worlds, and the very fact of its creation as a manifestation of Divine goodness.

Another gnostic principle found in some currents of Kabbalah is the idea of evil as an autonomous ontological entity that constitutes a world which is a negative reflection of the Divine world — “the other side” (sitra achra), or “the left side” (sitra di-smola). The image of evil in Kabbalah is linked to various mythological notions and an elaborate demonology. Like the Gnostics, Kabbalah acutely experiences the horror and hostility of the world in its perception of evil as the left side of being, in a constant tense sense of demonic presence in the earthly world. As early as the mid-13th century, a gnostic trend developed in Spanish Kabbalah known as the “Left Column.” Its first-generation representatives — the brothers Jacob and Isaac Cohen — developed a theory according to which there is a system of emanations of evil structurally analogous to the Divine emanations. This group of kabbalists paid particular attention to demonology, including the figures of Samael and Lilith. In their teachings, sexual motifs first appear, later taking on such an important place in Kabbalah.

For both Gnostics and Kabbalists the physical world is the result of a tragic error, a catastrophe in the Absolute, or an intrusion of the forces of darkness into the worlds of light (the concept of the “Fall” of the sephirot). The Unborn Father, revealing Himself, manifests in particular entities — aeons (in Jewish Kabbalah — the sephirot), often forming pairs or tetrads (syzygies). The completeness of these theophanies, aeons or sephirot constitutes the divine fullness (pleroma). The pride or error of one of the aeons (usually Sophia) leads to the disruption of this fullness, its fall from the pleroma, and the beginning of cosmogony, resulting in many imperfect worlds (sometimes 365) headed by their rulers — archons (in Lurianic Kabbalah, this tragedy is called “shvirat kelim” — “the Breaking of the Vessels”).

The next gnostic idea that found development in Kabbalah is the notion of the material world as a prison of the spirit, where particles of Divine light, enslaved by matter, are under the sway of non-being and chaos. Liberation from the prison of the world is achieved through participation in Divine knowledge (gnosis, which Kabbalah seeks) and through the apprehension of the nature of one’s own spirit as a particle of the one true God — the Absolute, the Unborn Father.

Both Kabbalah and Gnostic teachings, in turn, are developments of Neoplatonic ideas that arose from the fusion, at the turn of the Common Era, of Hellenistic and Eastern philosophical traditions.

Everything that had developed separately before then met and intermingled as a result of the cultural mixing caused by Alexander the Great’s conquests. From that time until the end of antiquity, the Hellenistic East produced a continuous succession of figures, often of Semitic origin, who under Greek names, in the Greek language and spirit, made a significant contribution to the dominant culture. On the other hand, after the Persians conquered Babylon, ancient Babylonian religion ceased to be a state creed attached to the political center and functioning as law. It was from the Babylonian tradition that a unique metaphysical principle was drawn and incorporated into the broader intellectual system: the system of theological dualism. This dualist teaching was one of the significant components of Hellenistic syncretism of ideas and later — of Gnosticism.

Most Gnostics also acknowledged a certain secret tradition inherited both from the biblical prophets (Adam, Seth, etc.) and from other sages of the past (Hermes, Zoroaster, Zostrian, Nikophanes, Allogenes).

Thus, on the one hand, by this time Greece had devised the logos, an abstract concept, a method of theoretical description, a system of thought — one of the greatest discoveries in the history of the human mind. On the other hand, Eastern thought was non-conceptual, expressed in images and symbols, more inclined to mask its ultimate aims in myths and rituals than to set them out logically. It was precisely by entering the formative stream of Greek thought that Eastern concepts took shape into what is known today as Kabbalah. At the same time, at first the Judaic strand of Gnosticism fit as little with orthodox Judaism as the Babylonian one fit with orthodox Babylonian religion, the Iranian with orthodox Iranian practice, and so on.

It is therefore traditionally said that Kabbalah studies, transmits, and develops the primordial extra-human knowledge about God, the world, and man. The formation of this “knowledge” lasted for millennia, absorbing achievements of both Eastern and Western thought.

In a broad sense, any gnosticism arises from the desire to know God, His “mysteries,” as Kabbalah puts it, and the riddles of the cosmos. Gnostics started from the sacred word, from the texts of the religion they professed, but interpreted them as if they contained a hidden idea, an esoteric meaning.

The peculiarity of Kabbalah as it exists today lies precisely in that it joined the pantheistic conceptions of Neoplatonism and the mythic motifs of Gnosticism with the Jewish belief in the Bible as a world of symbols.

In a broad sense, any Gnosticism arises from the desire to know God, his ‘mysteries’.

Reading through the time of publication, I discover something new. I am amazed by the depth of the articles.