The Gray Magic of the Heptameron

Since the question of the Heptameron has been raised, let us try to determine whether this book is as harmless as commonly believed.

Authorship of the “Heptameron or The Elements of Magic” is attributed to Professor Pietro d’Abano of the University of Padua (c. 1250–1316), a physician, natural philosopher, alchemist and astrologer who studied Greek in Constantinople, was suspected of heresy, and died in prison while under trial by the Inquisition. Although d’Abano was a close friend of Pope John XXII, he spent the last eight years of his life in prison. The Heptameron created for him, after his death, a reputation as a great sorcerer. It was even said that the devil carried him off after death. Frustrated that they had not managed to execute d’Abano, the inquisitors at least burned his portrait.

It was said that d’Abano kept seven demons in a glass jar, which made him a great master of the seven liberal arts (that is, in secular learning).

The first edition of the Heptameron was published in 1496 in Venice as an appendix to the works of Heinrich Cornelius Agrippa, following his Fourth Book. The book was also printed in Latin in Lyon around the sixteenth–seventeenth century transition.

The book lists in detail the signs, names and numbers one must know to summon the spirits called “angels of the air” in the book:

«and if they were to become acquainted with this work, they could learn the various functions of the spirits, how they can be summoned for conversation and discourse; what should be done each day and each hour»

The Heptameron is thought to be based on the most authoritative magical books, among them the Book of the Angel Raziel, which, according to tradition, the angel gave to Adam during his exile so that people could live on Earth and remember the Lord.

The Heptameron is mentioned in the Sepher Maphteah Shelomoh (the Book of the Key of Solomon), where it is called the Book of Light. Also, as one of the earliest books of medieval magic, the Heptameron is considered a principal source for the Lemegeton and the whole Solomonic cycle. Agrippa wrote that the works of Pietro d’Abano were one of the sources for his famous Occult Philosophy.

Arthur Waite regards the Heptameron as a continuation of Agrippa’s “Fourth Book.”

Waite first noted that the magic of the Heptameron “is not as white as it wishes to appear.” Although the spirits the Heptameron deals with are described there as angels, operations involving them proceed like those with demons — they are coerced by Divine names, threatened, and bound.

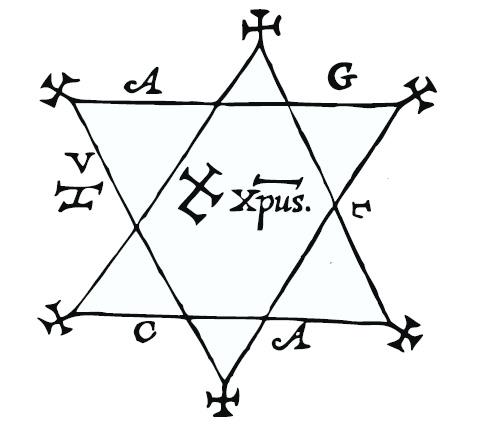

The Heptameron’s pentacle also is consistent with the general character of the Solomonic books: a hexagram bounded by crosses and the name AGLA clearly resembles, for example, the Almadel and other similar pentacles.

No less strange for angels are the aims of the operations: although they are ostensibly aimed at knowledge, among the duties of the summoned spirits are the traditional “opening locks or bolts”, “supply silver; transport objects between places; make horses faster and reveal people’s secrets”, “capable of causing wars, epidemics, death, and fires; provide two thousand soldiers simultaneously; bring death, disease, or health”, “seduce men into loving women”, and the like.

An examination of the nature of the summonings and the duties of the spirits shows that they are called “angels” only by pretense. In fact, the Heptameron deals with the same ministering spirits as the other grimoires.

In order to understand the character of these “spirits”, let us consider whom the medieval grimoires generally call “demons”.

From the Gnostics onward, the Christian esoteric tradition, with its concept of “fallen” spirits, placed these spirits not in “hell” or in the Qliphothic regions, but in the “subcelestial world“. And d’Abano, naturally acquainted with this notion, meant by his “spirits of the air” not elementals or elementals of the air, but precisely those “subcelestial” spirits.

We have already said that the magical tradition distinguishes ministering spirits who enact the descending current, those who obstruct that current, and those who reside in the vertical flow itself. It is the former — inhabitants of the Qliphoth and Sheol — who are predatory by nature, drawing power by their insatiability, and strictly speaking should be called demons.

Spirits that inhabit the flow are in principle capable of drawing power from its ascending part and therefore are not exclusive predators. Their “positive” ground, traditionally called “Genii”, is usually inactive. Nevertheless, they cannot generate power themselves, and therefore seek to devour life energy and the energy of desire (the “Red Light”) of Free beings.

Most Goetic spirits belong to this category — contrary to later representations, they do not come from “hell” but from “the heavens”, more precisely — from the “subcelestial” — inhabiting the vertical flow.

Therefore, d’Abano is entirely correct in conjuring his “angels”

«by the ruling cherubim; and by the great name of God himself, mighty and strong, exalted above all the heavens»

since this is precisely how name-based control of ministering spirits operates, including the “Gray” hierarchy.

Also important is the distribution of the “spirits of the air” among the “Winds”, i.e., among the cardinal directions, which helps, first, to choose the correct orientation for the operation itself, and, second, to understand certain characteristics of the spirits themselves. This division differs from the traditional allocation of spirits by planetary domains, but serves the same purpose, and can sometimes prove even more productive, although the Heptameron still lists the same seven regions and winds, corresponding to the seven days of the week. In some cases the winds and planets are sometimes equated, for example:

«The spirits of the Air of Monday belong to the West Wind, which is the wind of the Moon»

Thus, the Heptameron differs from the typical Solomonic grimoires only in technical details and in the manner of calling the Goetic (“Gray”) spirits “angels” or “spirits of the air”, so there is no special reason to consider it more “light” than, for example, the Lemegeton.

Okay. If the Demons of the Lesser Key are not Klippot, then which demons correspond to Klippot? By the way, is Astaroth of the Lesser Key and Astaroth of the Greater Grimoire the same entity, or are they ‘namesakes’? Just like Archangel of Fire Michael – this is not the same as the Archangel of the Sun, although they share the same name. And also – Sorat, Taftarat, Barzabel, and other planetary spirits – I understand, are also entities defined as ‘heavenly’? And if we are talking about planetary spirits, then what is the nature of the spirits of Arbatel in that case? These are entities of a completely different plane compared to Sorat and Taftarat, for example? Specifically, if we consider the accepted hierarchy in the West: Divine Name – Archangel – Choir of Angels – Genius – Demon, what place in this chain could the Spirits of Arbatel, presumably, hold?

1) Lemegeton is not a manual on demonology, but a practical guide. It describes spirits that are located in the decans and available for interaction with people. And among them, there are both ‘black’ demons of klippot, and ‘gray’ demons of the ‘heavens.’ The Astaroth you mentioned, like, for example, Sidonai – these are, without a doubt, absolute predators. 2) A name is an entity and there cannot be two different entities with the same name. Astaroth is always Astaroth, and Michael is always Michael, and regardless of which aspect of their activities is considered, their self-identity is preserved. If you consider yourself at work and yourself in a family circle – it may also seem that your functions and even personalities are completely different, but that does not mean that the entities are different. 3) Regarding Klippot in Western tradition, there is a habit of mixing the ‘husks’ as a principle and their inhabitants. As a principle, Klippot are a necessary component of existence; any object or partzuf must have its ‘husk,’ without which Power will not flow into it. Nevertheless, the spirits of klippot, despite their ontological necessity, are subjectively absolutely hostile to existence and beings. As for the spirits of Arbatel, they are probably also worth referring to the Gray hierarchy, but they express its neutrality, disinterest in the Flow of Power as such. 4) In the ZZ system, spirits of Arbatel should most likely be classified as Chinas, understood as the individualization of collectivities (in the spirit of Swedenborg).

I am shocked. In essence, this explains their inherent cunning. But there is a question about passages like ‘I summon you, Michael, do everything I need.’ In this way, do we include Michael in the hierarchy of the Heptameron and relate him to the heavenly?

Angels are also service spirits. In principle, they can also be summoned and called upon; the question is whether it makes sense to summon spirits whose very nature is to hinder the flow of Power.

So what do you mean by ‘that does it make sense’? Does a preliminary summoning corresponding to the day make no sense?

Summoning and calling are not the same. In traditional Evocation rituals, Archangels are called – just as the Names of the Most High are invoked, not to compel them to do something, but to identify one’s own power with their power. A magician identifies himself with the Forces that are on the same Axis of Analogies as those he calls upon, but standing above those called, thus gaining power over them.

Wait’s views on Black and White magic are quite controversial (at least those who compiled the Grimoires hardly shared the same opinion). But if working with the Heptameron implies working with the Spirits of Air – then perhaps it is rather gray magic. But in my opinion, it can be used as a basis for many other works.

In general, to be honest, I still do not quite understand what in practice your words mean that “Angels are spirits whose essence prevents the flow of power”. So, it is useless to call them for practical operations, but only, for example, to gain knowledge, etc.? Or is the work with them useful to the Magician for something else?

{Not taking into account the invocation to them as an intermediary link in the hierarchy during the invocation of lower spirits. They must still be remarkable for something besides that?}.

Calling Angels for practical purposes is not useless, but dangerous – and not less dangerous, and sometimes even more dangerous than calling demons. Have you tried to summon an angel? If interested – try – You are right, the Heptameron method can be used for any evocations (as can the method of any other Grimoire), and you will see for yourself what is particular about their nature…

I have tried to summon Angels and largely agree with you. For working with Angels, a person must possess certain qualities, and for those who do not possess them, calling them can indeed be dangerous {to the extent of this inconsistency}.

But to be honest, I still have not answered the question for myself – why work with them (especially compared to other spirits, with which interaction is often much more productive due to their greater proximity to human nature).