The Holy Grail — the Chalice of Peace

The counterpart of the Spear as the masculine symbol is the Chalice (the cauldron) as the feminine symbol.

The role of cauldrons and sacred vessels was of great importance in ancient culture, and the Grail Cup embodied that image, bringing it to its fullest expression.

The ancient Greek conception of the Horn of Plenty, which performed the typical functions of sacred vessels, is well known.

Horn of Plenty — an attribute of Gaia, Tyche, Plutus, Fortuna and others.

According to the canonical myth, it was made from a horn accidentally broken from the goat Amalthea, the nurse of Zeus. When Zeus grew and became the supreme god, in gratitude he brought her to the heavens, and she became the star Capella in the constellation Auriga. But on the way to heaven the goat Amalthea accidentally lost one horn. The nymphs picked it up, wrapped it in leaves, filled it with fruit and presented it to Zeus. Zeus returned the horn to the nymphs and promised that whatever they wished would pour forth from that horn.

Another myth relates that the Horn of Plenty was the horn of Achelous, the river-god, who took the form of a bull and fought Heracles. During the struggle Heracles broke off one of Achelous’s horns, which, at the nymphs’ request, became the Horn of Plenty.

As a horn, it is a phallic symbol; as a hollow vessel it is receptive and feminine, therefore the Horn of Plenty is an attribute of deities of vegetation, winemaking and fate, as well as of mother goddesses such as Demeter (Ceres), Tyche (Fortuna) and Althaea; Priapus also carries it as a sign of fertility.

In earlier times the Horn of Plenty (like all that related to wealth) was associated with Hades, the realm of the dead. The Horn of Plenty belonged to the god of wealth, Plutus. The similarity of the names Plutus and Pluto, lord of the underworld, is not accidental. In earlier tradition Plutus, like Pluto, was connected to Persephone. In the Eleusinian Mysteries, Plutus and Pluto were identified. The latter was thought to possess untold subterranean riches.

According to Celtic legend, the inexhaustible Cauldron of the Dagda is immense and resides in the feast-hall of the Otherworld (Sí). The cauldron is always full of pork, and only a coward receives nothing. Beyond abundance, the cauldron bestows new life. It was brought from the city of Murias — one of the sacred cities of the Tuatha Dé Danann located beyond our world.

Dagda’s Cauldron is inseparable from Lugh’s spear: the cauldron must first be filled with blood or poison, and then Lugh’s spear is plunged into it in order to strike down the enemies.

The Cauldron of the Dagda is the prototype of many wondrous cauldrons in Irish mythology and resembles the Horn of Brân, a deity closely allied to the Dagda in Wales.

Among the famous cauldrons of Celtic mythology are:

- The Cauldron of the goddess Ceridwen — its contents gave Taliesin omniscience.

- The Cauldron of Rebirth — revives fallen warriors. Once two giants gave this cauldron to Brân in gratitude for his kindness. The cauldron is carried by the giant Llasar. From Brân’s cauldron the fallen warriors emerge resurrected but mute. This cauldron, located in Annwn, is guarded by nine maidens — the embodiments of the nine worlds.

The Cauldron of Inspiration — whoever drinks from it is granted wisdom.

The role of such cauldrons played a significant role in Celtic culture, from the Gundestrup cauldron to the cup of the Holy Grail.

However, it is the Holy Grail that most fully embodies this ancient idea in its symbolism.

According to the familiar legend, the Grail is the cup from which the disciples of Jesus Christ drank at the Last Supper, into which later his followers collected drops of Christ’s blood of the Crucified Savior (the Instruments of the Passion). Joseph of Arimathea preserved the cup and the spear that pierced Christ’s body and brought them to Glastonbury.

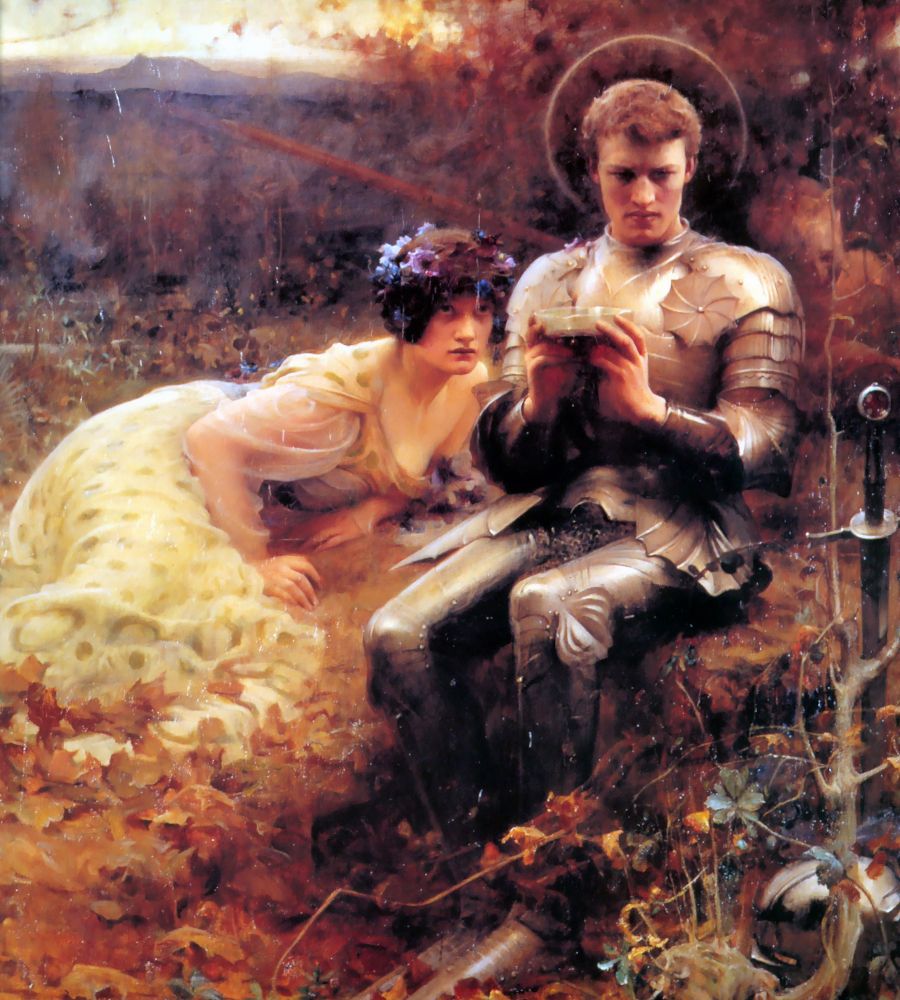

The theme of the Grail (the sacred cup) first appears in 1190 in Chrétien’s work the French poet Chrétien de Troyes, “The Story of the Grail”, which tells of the young Perceval, a retainer of King Arthur, who arrives at the castle of the mysterious Fisher King. During a meal a handsome youth enters the hall bearing a spear from which blood drips, and after him a beautiful young woman enters holding the Grail.

There it is described as a large dish inlaid with precious stones. During the meal it is passed around the table. The account says that because Perceval, intrigued, asked no question either about the Grail or about the bleeding spear, the curse remained in force: the Fisher King will not be healed of the wound in his thigh that has maimed him; his land will be ruined, hundreds of knights will perish, and many widows and orphans will don mourning.

Perceval — the “son of the widow” — is a designation belonging to dualist and gnostic schools, often applied to one of the prophets or to Christ himself, and later adopted into Freemasonry. Leaving his widowed mother, Perceval goes to King Arthur’s court. Many adventures befall him, and one night in the Fisher King’s castle, which has given him shelter, the Grail appears before him. But Chrétien gives no further explanation; we only learn that it is brought by a “very beautiful, slender and finely dressed” girl, and that it is “made of the purest gold” and adorned “with various stones, the richest and most precious to be found under the water and on the earth”. The next day Perceval leaves the castle without asking about the Grail, which everyone expected of him — about its origin and its meaning, about “who uses it” — an ambiguous formulation that can be taken literally or allegorically; this question should have lifted the spell. In any case, Perceval continues his way and learns that he belongs to the Grail family, and that his uncle is none other than the Fisher King who possesses the Holy Grail.

In other poems and romances the unusual word “Grail” is reinterpreted as a cup, a chalice, and even a stone.

The traditional depiction of the Grail as a cup first appears in the poem of the Burgundian poet Robert de Boron, “Joseph of Arimathea” (circa 1200).

This poem opens with an account of redemption, which the author treats as liberation from the devil. The romance then relates Judas’s betrayal, Jesus washing the feet of his disciples, and the Last Supper in the house of Simon the Leper. Joseph of Arimathea found on Golgotha the cup from which Jesus Christ had drunk, and he took it to the Roman procurator Pontius Pilate, who gave him the cup together with permission to take the Savior’s body down from the cross and give it burial.

Joseph took the sacred body of Jesus Christ in his arms and gently laid it on the ground. As he washed it he noticed the blood streaming from the wounds and was horrified, remembering that a stone at the foot of the Cross had been cleft by that blood. He also remembered the vessel of the Last Supper which Pilate had earlier entrusted to him, and the devout Joseph resolved to collect the drops of divine blood into that vessel. He gathered into the cup the drops from the wounds in the hands, feet and side, and then, wrapping Jesus’ body in rich cloth, laid it in a cave.

The news of Jesus Christ’s Resurrection greatly alarmed the Jews, and they resolved to kill Joseph and Nicodemus. Warned, Nicodemus managed to flee; Joseph, however, was seized in his bed, beaten severely and then imprisoned in a cell whose closed gate made the tower outside appear as a pillar. No one knew what had become of Joseph, and Pilate was deeply grieved by his disappearance, for he had lost a most loyal and courageous friend.

But Joseph was not forgotten. In the illumined cell there appeared to him He for whom he had suffered, and He brought the vessel containing His divine blood. Seeing the Light, Joseph rejoiced in his heart, was filled with grace and cried out: “Almighty God! From where can this Light come, if not from You?”.

“Joseph,” said Christ, “do not be discouraged; the power of My Father will save you! You will have unending joy when your life on earth is ended. I have brought none of my disciples here, because of our love nothing is known of it. Know that it will be manifest to all and dangerous to the unbelieving. You will possess a memorial of My death, and after you those to whom you entrust it. Here it is.”

And Jesus Christ handed Joseph the precious vessel of blood which He had hidden in a secret place known only to Him. Joseph fell to his knees and gave thanks, modestly indicating his own unworthiness. Yet Jesus ordered Joseph to take the Holy Grail and keep it. The Grail was to have three guardians.

Then Jesus Christ declared that the sacrament would never be celebrated without recalling the deed of Joseph of Arimathea. The Savior further communicated to Joseph mysterious words which Robert de Boron does not reproduce in his poem, and at the end said: “Whenever you are in need, ask counsel of the three powers that make one, and of the Maiden who bore the Son, and you will have counsel in your heart, because the Holy Spirit will speak to you. I will not take you out of here now, because the time has not yet come.”

After this Joseph’s family became its keepers, and the romances of the Grail recount their adventures and the vicissitudes of their fortunes. Thus, Galahad was said to be a son of Joseph of Arimathea, and his son-in-law Bron carried the Grail to England and himself became the Fisher King of those parts.

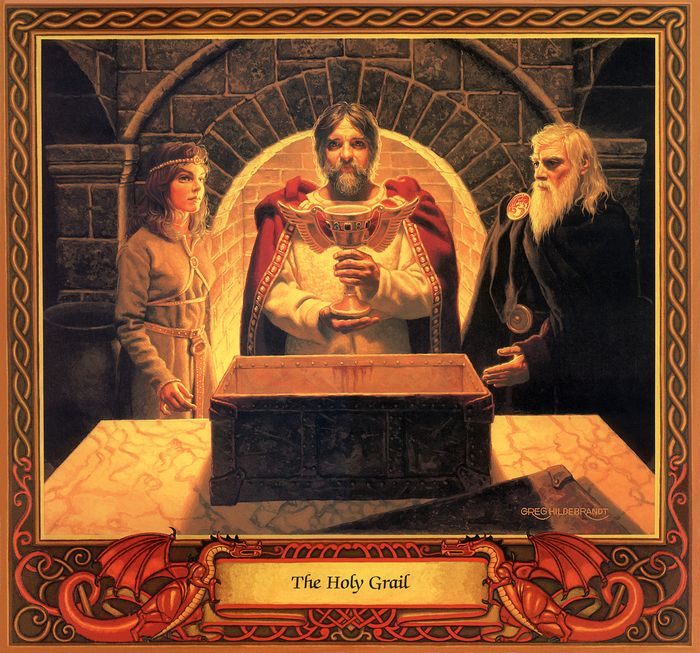

In the romance “The Quest for the Holy Grail” (1215–1230) appears Galahad, the virtuous and pure knight, son of Lancelot. The hero finds the Holy Grail, described there as a dish from which Christ ate the lamb at the Last Supper. In an ecstasy of rapture Galahad dies, and at that moment a hand from heaven reaches down and takes the Grail away.

Contemporary with “The Romance of the History of the Holy Grail” there appeared — perhaps in England — another prose romance, “Perlesvaus“, devoted specifically to Perceval’s quests. But, contrary to the prevailing convictions of his time, its author preferred to remain anonymous, from which one may infer that he belonged to a monastic or military order where such pursuits were deemed improper.

Perceval is repeatedly called there “most holy”; elsewhere he is said to belong “to the stock of Joseph of Arimathea”, and further — “this Joseph was his mother’s uncle, who served as Pilate’s warrior for seven years”.

And not only Perceval is designated the “son of the widow”, but the whole action of the romance unfolds in an atmosphere of strange ceremonies unexpected in a Christian context: a king is sacrificed, his children roasted and eaten — a crime often alleged against the Templars — a red cross is raised over the forest, a miraculous white animal is torn to pieces before Perceval by dogs; then a knight and a maiden appear who carry golden vessels and set about gathering the mutilated pieces of flesh into them before kissing the cross and disappearing. As for Perceval, he kneels before the cross and then, like all the others, kisses it in turn.

Later, during the mass, the Grail finally appeared “in five different forms, of which no one has the right to speak, for the secrets of this mystery must not be revealed, and only he to whom God entrusts them has the right to speak of them. King Arthur sees five different transformations, and the last of them is the Chalice (the cup)“.

According to Wolfram von Eschenbach’s book “Parzival“, written between 1195 and 1216, one who drinks from the Grail’s cup receives forgiveness of sins, eternal life, and so on. In some versions even a close contemplation grants temporary immortality, as well as various goods such as food and drink.

In that poem the Grail is made of emerald, beaten from Lucifer’s crown by the archangel Michael.

In his account of the Grail, Wolfram von Eschenbach gives the Templars an important role, for they are the guardians of the Grail and its household.

“…For no one can find the Grail unless so loved by Heaven that they point to it from above to receive him into their company…“. It is guarded by those “upon whom God Himself has pointed”… What, then, is the Grail for Wolfram von Eschenbach?

First and foremost it is the mysterious object barely hinted at by Chrétien de Troyes: “…She was dressed in Arabian silks. On green velvet she bore a majestic object unequaled even in Paradise, a perfect thing to which nothing could be added and which was at once root and flower. This object was called the Grail. There was nothing on earth that it did not surpass. The lady whom the Grail itself entrusted with bearing it was called Repanse de Schoye (‘Repanse de Schoye’ — ‘One Unacquainted with Wrath’). The nature of the Grail was such that one who cared for it had to be a person of perfect purity and refrain from every treacherous thought“.

Then it becomes a kind of Horn of Plenty, containing all happiness and all the pleasures of the world: “One hundred pages were commanded to present themselves respectfully to the Grail and to collect the bread which they then wrapped in white napkins… I have been told and I repeat to you…, at the Grail the companions found every dish they could possibly desire, ready to be eaten… But, say those who hear me, nothing like this has ever been seen on earth. Do not doubt it. For the Grail is the flower of all happiness; it brings to earth such a fullness of benefactions that its merits were almost equal to those that can only be seen in the Kingdom of Heaven“.

And even here the reference is still to the earthly and material, without any specific power vested in the object. But later Parzival will hear from his hermit-uncle a completely different definition of the Grail, resonant with gnostic thought: “The valiant knights live in the castle Monsalvat, where they guard the Grail. These are the Templars, who often travel to distant lands in search of adventures. Whatever the outcome of their battles – glory or disgrace – they accept it with an open heart as the expiation of their sins… All that they eat comes to them from the precious stone, whose essence is purity… It is called ‘lapis exillis’. It is by means of this stone that the Phoenix burns itself and becomes ashes; it is by means of this stone that the Phoenix moults, to appear again in all its splendor, more beautiful than ever. There is no sick person who, in the presence of this stone, would not be guaranteed to escape death for a whole week after the day on which he saw it. Whoever sees it ceases to age. From the day the stone appeared before them, all men and women assume the aspect they had in the prime of their strength… This stone gives a person such power that his bones and flesh at once regain their youth. It is also called the Grail.”

Since the guardians of the Grail are Templars, its owners are accordingly members of a special family with many branches scattered across the world; some of them do not even know who they truly are. One of these branches dwells in the Grail castle, Monsalvat, later the legendary stronghold of the Cathars, Montségur, which met the same fateful end as the castle of Montségur. This castle was populated by mysterious figures: the guardian and bearer of the Grail Repanse de Schoye and Anfortas, the Fisher King, as in Chrétien de Troyes — Parzival’s uncle, lord of those lands, who bears such a wound that he can neither beget nor die. And when, at the end of the poem, the curse is lifted, the heir to the Grail castle will be Parzival. The servants of the Grail must also be initiated into some secret; sometimes they are sent into the world to act on its behalf and later to occupy a throne, for the Grail has the power to create kings: “Fortune often grants to the knights of the Grail a happy fate: they help others, and fate helps them. They receive young men of noble birth into their castle, handsome in face. Sometimes a kingdom finds itself without a ruler; if the people of that kingdom are obedient to God and if they wish to have a king chosen from the host of the Grail, their wish is fulfilled. It is necessary that the people respect such a chosen king; for he is protected by God’s blessing…”.

Elsewhere we seem to understand that in the past the Grail family incurred divine wrath, and the hint of “God’s anger toward them” brings to mind numerous medieval texts about the Jews. It also calls to mind a mysterious work inseparable from the name of Nicolas Flamel: “The Sacred Book of Abraham, Judean, Prince, Priest, Levite, Astrologer and Philosopher of the Hebrew tribe, which by reason of God’s wrath was scattered among the Gauls”.

Phlegetanis, the presumed author of the original account of the Grail, was, according to Eschenbach, a descendant of Solomon. In that case, it is quite possible that the Grail family had a Jewish origin. Whether it had been cursed in the past or not, in Parzival’s time it openly enjoys divine favor and considerable power. Nevertheless, it must not reveal its identity: “God sends His elect in secret…”. As a rule, women may reveal their origins, but men are absolutely forbidden to do so, and they must not allow any question on the matter. This is an important detail, as Wolfram von Eschenbach returns to it at the end of his poem: “An inscription appeared on the Grail. It read: if ever God should point to one of the Templars to become the king of another people, knight must demand that no one attempt to learn either his name or the family from which he comes. As soon as such a question is put to him, he must go away and not return”.

Because no single version of the Grail story became authoritative, “Grail” texts spread with variant readings. More than a dozen such texts survive, all written between 1180 and 1225 in French or adapted from French originals; yet each contains its own version of episodes, full of ambiguities and contradictions, which in itself contributes a good deal to the charm of the Grail legends.

In all the medieval romances about Perceval the hero seeks and finds the magical castle Monsalvat, in which the Grail is kept under the guardianship of the Templars.

Undoubtedly, this conception rests on legends still current, the Grail’s guardians were the Templars. According to this legend, Joseph of Arimathea founded a brotherhood, a monastic-knightly order whose members were called Templays. They were the first custodians of the cup, and despite desperate resistance offered by them in the 5th–6th centuries to the Saxon invaders of Britain, they were compelled to transfer the relic to Sarras, whence it “was carried up to heaven” and its traces in history were lost. Centuries passed, and increasingly in the early Middle Ages songs and ballads began to tell that the exploits of King Arthur, who led the Britons against the Saxons, and the knights of the Round Table were linked to the return to Europe of the sacred relic — the Grail. The legends sing that the holy cup returned thanks to the courage and daring of the celebrated Perceval. He succeeded, not without Merlin’s help, in breaking the evil spells and the cunning plots of the wicked enchanter Klingsor, and in attaining the Grail safely. From then on he — a selfless warrior who devoted his life to the service of good — guarded the treasure in the impregnable castle of Montségur.

In parallel, as a result of one etymology, the name Sangrail was interpreted as sang real (“royal blood”) and came to mean the blood of Christ, as well as the Merovingian lineage, alleged bearers of that blood.

However, such a reading does not at all eliminate the conception of the Grail as a vessel.

For hundreds of years books about the Grail were creations wholly embodying the ideal of the nobility. Aristocrats collected them in their libraries, and after lavish libations their guests from noble households entertained themselves with them. Ignorance of the tales of the Knights of the Round Table was considered a sign of vulgarity; the names of the characters (Arthur, Lancelot and others) were given to infants at baptism, and so on. Even Merlin appears in the romances as a zealot of Christian principles. Thus, having once endowed a poor man with wealth and honors, he took them away when the man became proud and showed himself ungrateful.

Possession of the Holy Grail was always regarded as the cherished dream of many knightly orders. The Knights of the Round Table, the Templars, the Teutonic Knights — all sought in vain to find this mystical vessel in order to master its divine energies.

The Grail legend achieved its greatest fame after the works of Thomas Malory, author of eight Arthurian romances compiled into a collection he called “Le Morte d’Arthur”, published in 1485 by W. Caxton in one volume under the title “The Death of Arthur“. Malory was a knight of Newbold Revel (Warwickshire); he was born at the beginning of the 15th century and spent almost the last twenty years of his life, with few interruptions, in prison on various charges. He belonged to an old Warwickshire family and in 1444 or 1445 represented his county in Parliament. In the autumn of 1462 he accompanied the Earl of Warwick and Edward IV on a military campaign to Northumberland, and when Warwick defected to the Lancastrians, he followed his example. In 1468 Malory was twice removed from the lists of Lancastrians to whom Edward granted amnesty. Malory died on 14 March 1471 and was buried in the church of the Greyfriars (Franciscans) in London. Most, if not all, of Malory’s works were written in prison. Besides the French romances of King Arthur, Malory also drew on English writings, which he, however, never cited. It is believed that the total volume of Malory’s sources was five times the length of his romance.

In Malory the Grail is mentioned as a cup: “But lo, the Holy Grail appeared in the hall under a white silken cloth, yet none were allowed to see it nor her who bore it. Only the hall was filled with pleasant scents, and before every knight appeared meats and drinks most agreeable to his taste.” In his works the Grail also performs the function of a Horn of Plenty.

In later legends Sir Galahad acquires special significance: the pure Knight, the only one among King Arthur’s knights who was privileged to see the Holy Grail in its true form.

According to these tales, the search for the Grail — the cup containing the blood of Jesus Christ, which Joseph of Arimathea collected — was the principal aim of the Knights of the Round Table, and one of the seats at the table was always kept empty for the one who would find the Grail, until it was occupied by Sir Galahad. Any knight who sat in it before him sank through the earth. The young knight sat in the forbidden Perilous Seat, which was reserved only for that most worthy of the worthy whom God Himself protects.

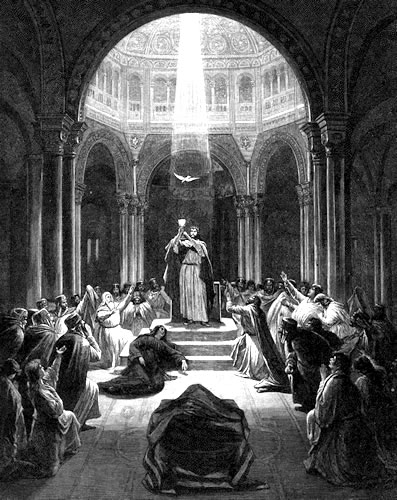

Once, after a battle with a fearsome dragon, Sir Lancelot met King Pelles, a descendant of Joseph of Arimathea. Seeing the knight exhausted by battle, the king invited Lancelot to his castle to lodge. In honor of the noble guest a wondrous banquet was provided: into the main hall entered the beautiful Elaine, daughter of King Pelles, carrying in her hands a golden cup — the Grail — which, after the prayers of all present, filled the cups and plates of those assembled with every kind of food and drink. And, seeking to endear the knight whom he planned to wed to his daughter, King Pelles revealed to Lancelot a secret: the Round Table will cease to exist the day the most precious treasure — the Holy Grail — is lost. The illegitimate son of Lancelot and Lady Elaine, Galahad, was reared from childhood by monks in a monastery. The youth grew extremely devout, famed for his gallantry and purity. On the day of Pentecost Galahad arrived at Camelot to be knighted by King Arthur. That day the assembled knights were shown a vision in the form of a golden cup covered with cloth, which the knights recognized as the Holy Grail — the cup into which Joseph of Arimathea had gathered the blood of the crucified Jesus Christ. After that many knights of the Round Table, Galahad among them, vowed to set out on the quest for the sacred cup. Various miracles ensued thereafter, and Sir Galahad even had to become king for a time, but he patiently awaited his longed-for departure from this world. Many knights rode with the young Galahad in search of the Grail, but only two of them — Sir Bors and Sir Percival — were permitted by the Lord to be near the young Galahad at the time of the Grail’s appearance in the castle of Corbenic, the castle of King Pelles. Only after receiving communion from the long-deceased Joseph of Arimathea was Sir Galahad able to hold the Grail in his hands, and then, when he reverently knelt to pray for his deliverance, his soul was suddenly freed from his body and “a great multitude of angels bore it up to heaven”.

Parzival and the search for the Holy Grail held particular appeal for Nazi initiates in Fascist Germany. Richard Wagner’s musical interpretation of the Grail legend made a profound impression on Nazi mystics. One of them, Otto Rahn, inspired by the story of Parzival, set out in search of the Grail.

In 1931 he traveled to France and reached Montségur — the last stronghold of the heroic defense of the Albigensian Cathars. Legend has it that it was from here, on the night before the decisive assault by papal crusaders, three Cathar heretics slipped away unseen, taking with them the sacred relics. At great risk to their lives they preserved the magical regalia of King Dagobert II and the cup thought to be the Holy Grail.

Thus, the search for the Grail — the eternal quest for power and truth — is symbolically a way into the pre-manifest, the pre-natal state, since the cup — the symbol of the Fruitful Womb — constitutes an inseparable road to Eternal Femininity, just as the search for the Spear represents the Way to Expansiveness. It is no accident that in every Grail legend the object — whatever it may be — is held by a woman.

“To gain knowledge on how to use the Grail is not enough; one must also possess it, and to possess it, one needs to have the spear of power…”

The Grail in paganism, referred to as ‘The Witch’s Cracked Cauldron,’ signifies one concept—an installation that can form the necessary atoms of any matter from an infinite number of particles (toroidal vortices) based on their size, due to pressure in the ‘cup.’ By changing the phases (sizes) of the particles, we also generate cold electricity (energy). The Grail is essentially a mini black hole, where some knights (particles) perish while others are immediately born. This follows the principle of the phoenix! In the word ‘Phoenix,’ FЁN represents the wind blowing from the mountains (into the horn); IКS symbolizes the very cross transforming into the letter y (U), which gives us Adam’s rib for Eve. This rib serves as the wall (stone) against which the initial particles collide and become the material for the creation of new ones in this severed sword TOR (cauldron)!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!

Dear ‘mastermag’! I strongly recommend that you take your theory of “cold” and other “semi-sweet” electricity to the nearest physics institute. They will provide you with qualified assistance in evaluating your guess 🙂 And here, regarding Magic – it seems this is slightly outside your profile.

Your publication about the Holy Grail is the most complete and successful version concerning the essence of the phenomenon. You give the correct definition of the cup directly, albeit provided that readers have reason. Anyone can possess the cup, which offers the opportunity for healing from any illness, rejuvenation, and significant prolongation of life. With rational use, knowledge of ancestors can be attained and the ability to know the future. An analysis of what is presented in the article should be conducted, and conclusions should be drawn regarding the cup. What the cup is and how to use it is a separate topic. Unfortunately, we wait for discoveries from science in the field of health and from religions in deciphering written documents of the past. All of this is accessible to any person. Dare and make efforts to achieve your goals. Good luck to you.

I am deeply convinced that the cycle of novels about Arthur and the knights, a medieval reinterpretation of the same legends that lie at the foundation of Tolkien’s works… for example, Aragorn – Arthur, Gandalf (Mithrandir) – Merlin, etc. In this case, in the legend of the Grail, the plot of the search and return of the Silmaril by Beren can be seen, a plot that is significantly earlier in time than the era of Arthur – Aragorn.

Beren, seeking and returning the Silmarillion – the plot is truly modernist.