The Unloved Children

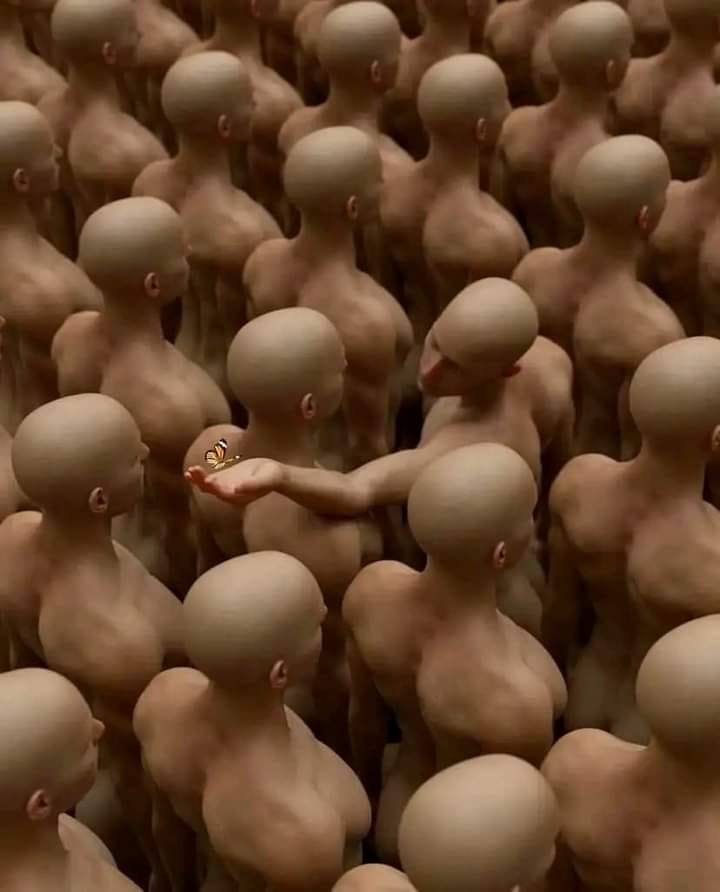

We live in a world where many societies do not have, or have lost, a culture of love for children. For a significant number of families in such societies, a child is merely an extension of their parents’ selfishness, an element of the “family” as a socially approved and publicly judged institution. In these families, what is valued in the child is obedience to parents and conformity to social norms and standards; the child functions as an object of pride and an element of competition (who has the better, more successful, more beautiful, etc.).

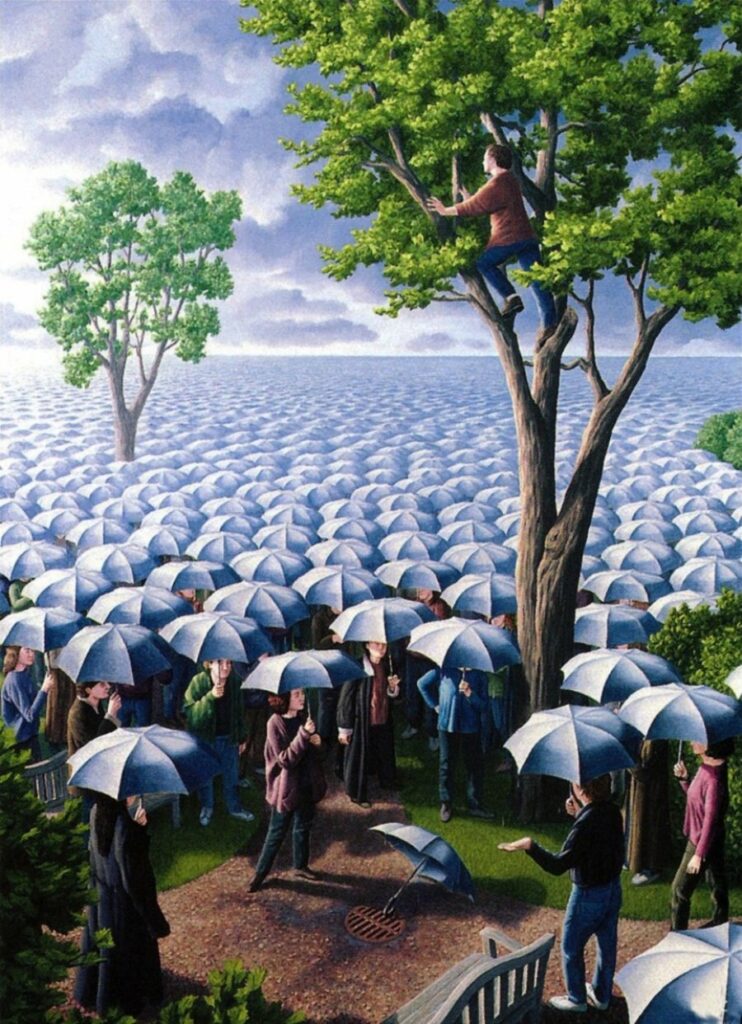

As a result, the child is not taught to recognize and value their individuality; they grow up with the conviction that love and the approval of society must be earned by fulfilling requirements and trying to conform to socially accepted criteria. It may not occur to the child that they might be loved “just because” — not for something and not for some reason, but simply as a unique, irreplaceable individual whose chief value lies precisely in its individuality. When, during the adolescent “rebellion” and search for self-determination, such a child tries to find “their place,” lacking the skill of identifying the self, they do not go beyond simple opposition, which, of course, is easily suppressed, and the wounded spirit, never truly awakened within, is firmly locked in the dungeon of unrealized potential.

Over time, the role of the parents is taken over by the state and the government, and the child, raised as a means of their parents’ self-gratification, begins trying to please “those in power,” feeling like a means of ensuring their well-being, not seeing any independent goal and value of their own.

This is how entire cultures of “non-love” are formed, in which individuality is devalued, while conformity, on the contrary, is welcomed and encouraged.

At the same time, societies built on a devalued individuality nevertheless always, in one way or another, cultivate a sense of separateness: all attempts at social adaptation based on suppressing the uniqueness of an individual being end only in an imitation of community, a “false unity.” A person not taught to value their uniqueness does not see or value the uniqueness of others, and therefore behind the outward “social commonality” of cultures of non-love, there is always inner alienation, suppressed aggression, and a more or less veiled struggle “for a place in the sun.”

As a result, two groups are formed in societies: a conformist majority that blindly follows imposed ideas and retransmits the narratives “sent down” by social drivers, and narcissists who overcompensate by imitating love with simple hedonism. The first group constitutes an inert mass, easy to control and ready to sweep away anyone who does not match its notions of “normality.” The second group confuses love with self-admiration, compensating for being “insufficiently loved” by parents with fantasies about “God’s love,” “rays of kindness,” and similar surrogates. A simple criterion that makes it possible to understand that these ideas are merely overcompensations — fantasies substituting for genuine emotional connections — is the endless egoism of these “adepts of universal love.” They are usually completely devoid of compassion and any inner sense of others’ reality other than their “enlightened” self.

Unfortunately, for a person who grew up in such a culture but who truly wants to change, correct, and redirect the distorted emotional patterns formed in them, there is no simple solution. All the energy that their parents should have expended in forming in them a sense of their own value and uniqueness (along with the same absolute value and uniqueness of others), they will have to expend on their own, step by step training themselves to see the essential and natural features of their mind, without adjusting it to someone else’s criteria, yet without becoming oppositional.

The task of a person striving for “correction in love” is not to fall into extremes or narcissism, but to learn to recognize and acknowledge the value of each individual’s uniqueness, to cultivate empathy and active, practical compassion within oneself.

Only when we learn not to “love ourselves as we are” (since this fashionable phrase means nothing but self-preservation in the rotten manifestations of a corrupted psyche), but to “love what we can become,” when we learn to find and support within ourselves manifestations of love and compassion, our pure original nature — not because it is “right” or “good,” but because it is natural — will we take the first step toward healing our spirit. The second step should be exactly the same recognition of the value of any other natural and healthy individuality, regardless of how much it differs from our own. And besides this, one should uproot in oneself the habit of seeking “parents’ approval,” projected onto surrogate authorities — the state, religion, and any other social institutions.

The last words spoken in life by Buddha Shakyamuni were: “Be lamps unto yourselves, and walk in your own light.” On the one hand, this saying emphasizes individuality, and on the other — luminousness. Therefore, if we want to follow the path of Enlightenment, we must ask ourselves two questions: 1) Do I remember my individuality and its value? and 2) Do I carry light — does it become lighter (and warmer) for others because of me?

I completely agree with the author. Only children are the continuation of their parents, who lived in similar systems. Perhaps worse, since they didn’t have the Internet.

As Bulgakov wrote, cowardice is the greatest sin on earth. By overcoming fear, we acquire individuality. The fear of loneliness.

Could you please tell me who Samuel is? Thank you.

https://enmerkar.com/en/myth/the-poison-of-god-two-samaels