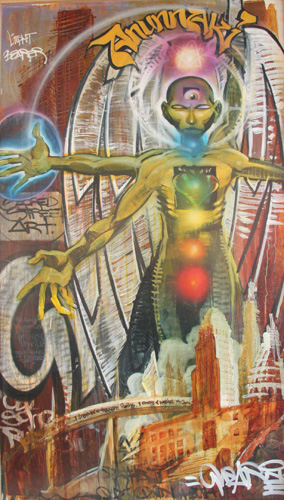

Annunaki — Judges of the Underworld

And the Annunaki, the Dreadful Judges

The Seven Lords of the Netherworld

surrounded her

Faceless Gods of the Abzu

They gazed and enchanted her

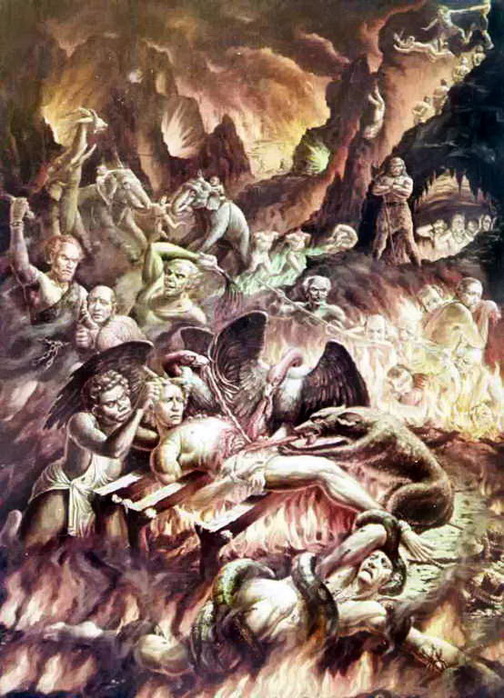

with the eye of death they slew her, with the Gaze of Death they killed her

And they hung her like a flayed carcass

Sixty demons tore her limbs off

Eyes from her head, ears from her skull.

Mesopotamian notions of postmortem existence are as elaborate as those of the Egyptians or Buddhists, although, unlike the latter two, they are not compiled into “Books of the Dead.”

If, according to Egyptian myths (and, correspondingly, ancient Greek ones) the Judgement of the Dead gives the soul a chance to enter Paradise (“Fields of Iaru,” “Elysian Fields”), Chaldean culture imagined a darker — and apparently, more believable — picture.

After the Gallu — demons who extract the soul from the body and convey it to the abyss of the underworld — the Annunaki dismember the soul.

The Gallu delivered the soul to Ki-gal (lit. “great land,” “great place”), or Kur (lit. “mountain,” “mountainous land,” though conceived in the “lower” world) — in Sumerian culture — and to the corresponding Erçetu (“earth”) or Kur-nu-gi (“land of no return”; borrowed from Sumerian) — in Akkadian culture. There the judges dwelt.

The Annunaki are first mentioned in the Babylonian creation myth, Enuma Elish. According to the late Babylonian myth, the Annunaki were the children of Anu and Ki, brother and sister — Heaven and Earth. (“once, on the mountain of earth and heaven An begot the Annunaki“).

Why “on the mountain”?

Because death came with the Annunaki into the world. Before their arrival the souls of the dead dwelt among the living as Shedu or Lamassu, protecting them.

It was precisely the Annunaki who, by seizing the deceased’s consciousness, condemned it — if it failed to pass into Kur — to become an Utukku — a wandering vampiric demon that brings misfortune.

Originally the name Annunaki designated precisely the gods of the netherworld, spawned from the “Darkness of the Heavens.” But gradually this name lost its ominous meaning and came to be applied to all the gods — the children of Anu. We will use the original, darker meaning of the name Annunaki.

Thus, the task of the Annunaki is to separate a deceased person’s energies into their components, and in this sense they are, on the one hand, the necessary forces of disembodiment, but on the other hand — forces opposing the integration of the soul that should be achieved in the postmortem journey.

The Annunaki were conceived as “dividing” deities: “The great Annunaki, determiners of fate, having gathered counsel, apportioned the land into four quarters.”

What the Annunaki discovered when they examined the soul of the deceased determined its further fate — to be cast back into Gilgul or to rot slowly in Kur, serving as food for the demons inhabiting it. The second scenario was more likely for a mind that has not achieved its wholeness.

In Mesopotamian conceptions the figures of the Annunaki were far more grandiose than those of the demons, rivaling only the higher gods — the Igigi or Asag.

Their number varies in different sources from four to several thousand; in Babylonian times they, like other beings (for example, the Gallu), were counted as seven principal and a thousand lesser ones.

In any case, the judgment of the Annunaki is always harsh, and the Sumerians knew of no favorable outcome in the afterlife. It is not that they were unaware of a “paradisal garden” (it lay in Dilmun), but that place was only the dwelling place of the gods, not of humans.

The word “Kur” originally meant “mountain,” and later acquired a more general sense — “foreign land,” because the surrounding mountainous regions posed a constant threat to Sumer. From the viewpoint of Sumerian cosmology Kur represented an empty expanse between the surface of the earth and the primeval ocean. It is there that the souls of the dead descended. On the way to Kur the dead passed through seven gates of the underworld, where they were met by the chief gatekeeper Neti. The boundary of the underworld was the river “that swallows people,” across which the dead are ferried by Ur-Shanabi — servant or embodiment of the “Great Vizier” of Kur — Namtar.

If the soul became stuck in Kur, it was entirely dependent on offerings from the living, which were its only sustenance; in turn, it served as food for the numerous demons.

This is why the Sumerians believed that a person’s duty was to provide the gods with food and drink, to increase the gods’ wealth, to erect temples for the inhabitants of heaven. When death comes, one can no longer serve the gods, becomes superfluous, is turned into a shade and departs to the “land from which there is no return,” to wander there aimlessly, tormented by demons. No one can escape their fate; one can learn something of one’s future from priestly divinations, but it is impossible to change one’s lot. The will of the gods is unalterable and incomprehensible. The only salvation is to find a substitute.

The Annunaki, seated before Ereshkigal, sovereign of the underworld, pronounce only mortal judgments. The names of the dead were entered in a tablet of the underworld by the female scribe Geshtinanna.

A more favorable decision for the soul was to be “raised up,” that is, to return to Gilgul and again accumulate energy.

Nevertheless, a human was regarded merely as fodder for otherworldly predators, who could, however, be temporarily appeased by substitute offerings.

Thus, the Annunaki are, on the one hand, forces necessary for disembodiment and reincarnation, since they ensure the severing of internal knots and attachments in the mind, just as the Gallu relieve the mind of attachments to the “external.” Yet if a mind has not developed a strong drive toward wholeness, if it has not been trained in integration, the Annunaki become its “judges” and “executioners,” destroying everything that can be, and therefore, in their view, must be destroyed, making the postmortem journey a path of suffering through Kur — the otherworld.

If the Anunnaki sent the soul to Kur, where it slowly decomposed, serving as food for demons, then this is the “World of Retribution”, where “the causes of ineffective existence are eliminated”, and the soul will ultimately be thrown into Gilgul? And do offerings from the living speed up this process for souls stuck in Kur? And for what reasons can a soul get stuck there?

In the case of Sumerian mythology, Kur is, of course, the World of Retribution. Souls can get stuck there in case of disruption of disincarnation, for example, due to a large number of accumulated connections, debts, or attractions.

As I understand it – Kur is one of the options for completing human incarnations. Immortal mages are unlikely to end up there, right?