Alastor: the urge to inflict pain

Nothing is more dangerous than someone assuming the role of judge. Lacking full knowledge, not seeing all the connections, causes and consequences of a given phenomenon, the desire to restore justice and balance becomes a path to increasing pain and suffering.

The ancient Greeks called the spirits of vengeance Alastors and regarded them as a form of the Erinyes — goddesses of retribution. There are many legends about how these spirits avenged various murders and crimes. More generally, Alastor was regarded as one of Hades’ steeds — that is, a means of transport for the god of death.

The ancient Romans adopted this notion of spirits — avengers who bring death and torment.

As early as Euripides, Alastor is not simply a spirit avenging a previously committed crime, but an evil spirit that seduces people into crime, and then, more broadly, a spirit of calamity and ruin.

In the Middle Ages, the power of Alastor was reinterpreted and presented in a more cosmic guise — the image of the infernal executioner.

In this vein, J. de Plancy describes him in his Infernal Dictionary:

“Alastor is a cruel demon, the supreme executioner of the infernal monarchy. He acts as an inexorable avenger…”

Crowley, however, somewhat romanticizes the image of Alastor, taking the name as his own — Aleister — and calling him “the Spirit of Solitude.”

Yet the power described by this spirit is ambiguous, complex, and far from romantic.

On the one hand, any system displaced from equilibrium strives to return to it, and a corresponding force arises within it. It is precisely this force that is regarded as “the force of justice,” and it was personified in the image of Zeus Alastor, who punished criminals, or the Old Testament Yahweh, who commanded an “eye for an eye.”

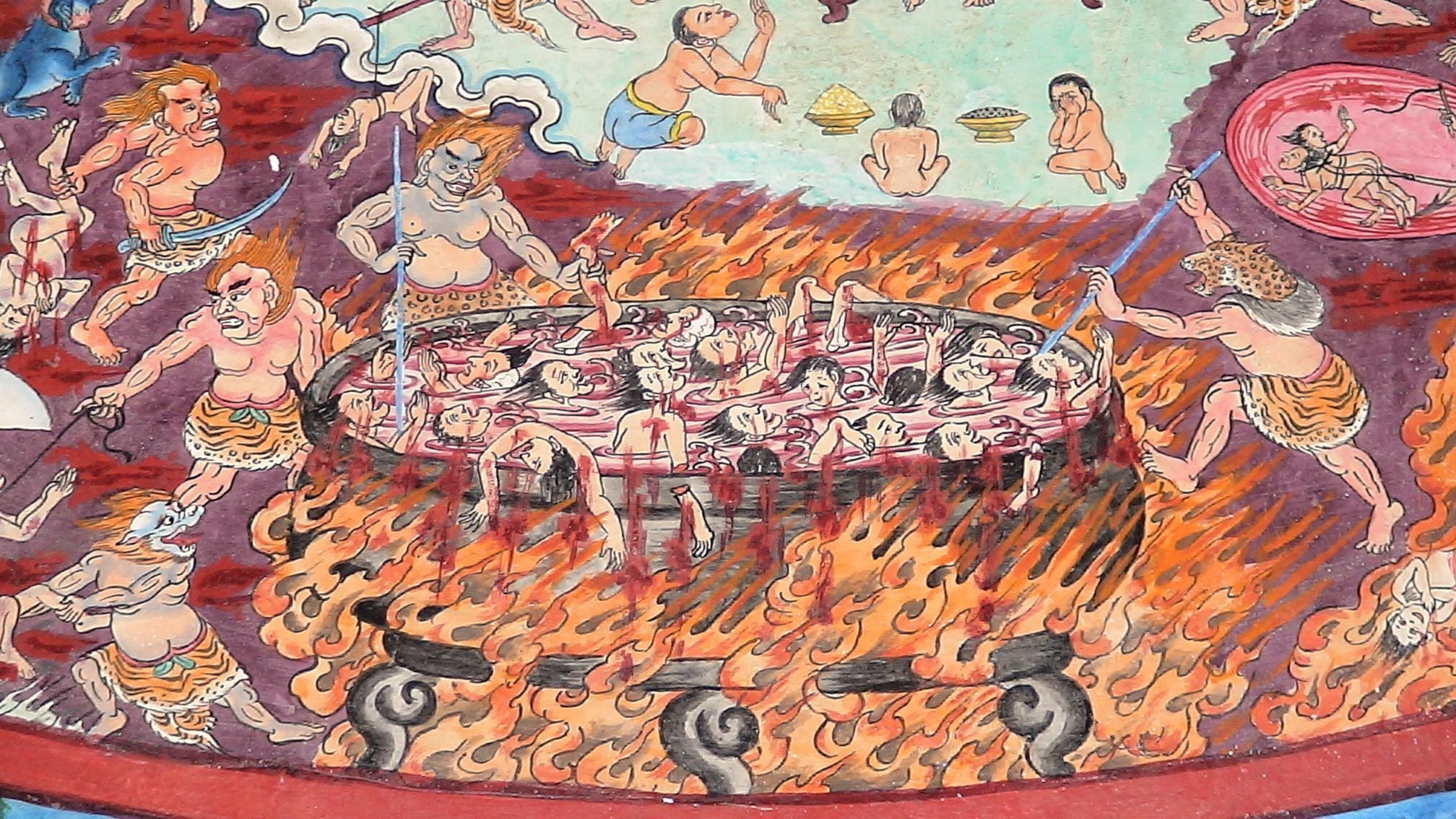

In this sense, “Alastors” are called “forces of self-punishment” appearing in the afterlife — those “infernal executioners,” “servants of Hades,” or the “retinue of Yamaraja” that appear to the deceased as hostile beings that inflict pain, although in fact they are the products of one’s own guilt and responsibility for the “evil deeds” committed.

As with many other forces of the afterlife, Alastors are both beings and essences, spirits and illusory visions, and although one can discern will and intention in them, they are generated by the karmic imprints of beings losing their bodies.

On the other hand, when distorted, this force turns into a drive to inflict suffering, and this drive very often manifests in the human world.

When, in an overcrowded subway car, people shove each other, it is not merely an attempt to “restore balance” — “I was shoved, and I will shove back.” In practice, it often happens that the pushing is deliberate, not intended as “retribution,” but simply to cause pain, out of aggression and cruelty that merely masquerades as “justice.” This tendency reached far greater proportions in times of mass repression or war.

It is precisely this force — cruelty for cruelty’s sake, concealed under a respectable pretext — that is described by the image of the “infernal executioner.”

Alastor is not merely sadism, not merely pleasure in another’s pain; it is “sanctified sadism,” sadism justified by “good ends.”

Detecting this force within oneself can be very difficult.

How does one distinguish “righteous anger,” a genuine striving for justice, from the influence of Alastor, from the urge to inflict pain?

In this key, one can recall a well-known utterance of the Buddha:

“Hatred is not destroyed by hatred, it only increases it…”

Anger, as a manifestation of the fiery principle, is free from evil and hatred; its aim is not to increase suffering.

The Magus is not a sanctimonious figure, blissfully smiling at his opponents. But the Magus is also not a vindictive avenger, who delights in another’s pain.

Another’s pain pains the Magus more than his own pain, and he always, in every action, strives to reduce overall suffering in the world.

The Magus does not assume the role of judge, does not attempt to assess others’ actions and “punish the unworthy.” His battles are battles for freedom.

Only when his actions reduce the overall amount of suffering in the world can the Magus consider himself an effective warrior.

And to avoid manifestations of cruelty, to avoid inflicting pain, is precisely the path to freedom, since it means freedom from Alastor.

As always – Thank you for the article. As I understood, Alastor is not among the 72. He has no counter in the goetic-theurgic sense. To which spirits, which hierarchy do similar spirits (like Alastor, Fagogo, etc.) belong?

Not all Gray spirits are goetic, in the sense that not all of them are Gatekeepers. However, dwelling on the Edge makes their task the same – dispersing energy. At the same time, Tradition often considers Alastor as one of the “faces” of the King of Repulsion – Belial. The energy dispersed under the influence of Alastor most often flows through the gates of Glasia-Labolas or Flaurus, just as, for instance, the energy torn away by Belphegor predominantly flows through the gates of Asmodeus.

Good article. I also believe that energy should not be wasted thoughtlessly. But all these battles for freedom… You know, I encountered the extremity of this. These are the Jews. I love one of them. She considers herself Kali. And the way she behaves… And at the same time considers herself a judge and savior, bringing light. Freedom from everything, matter, feelings… In short, they are plants or dry sticks, not humans. The only thing that warms them is to become creators. But the methods and sacrifices… It’s just terrible. The dark hierarchy governs them. Many of them even agreed with me…

In Judaism, there is no Kali. Most likely, she is not Jewish.

From a Buddhist point of view, there is no difference between anger and hatred.

Anger goes from top to bottom, to the root, burning away the disgusting, clearing space for a new order. Hatred denies, blinds, erases, leads away.

One of the most sophisticated manifestations of this demon is THE CALL TO JUSTICE. Justice, as an entirely subjective component, is applied by this demon as an alternative to all that could serve for the development of the magician’s power. It is this demon who forces one to view certain demands of the teacher as UNJUST and compels one to resist them, expending the energy of the pupil on MOVING AGAINST THE WAVE. He also compels one to view any changes of fate as unjust, again invoking the MAGUS’S MOVEMENT AGAINST THE WAVE, instead of USING THE ENERGY OF THE WAVE. The most important thing is that this demon diverts the magician’s power into a distraction struggle for mythical global justice, a fight that can completely absorb all of one’s life span and consciousness, as is exemplified by magicians drawn into revolutionary events throughout the ages. Resisting the temptation of the demon – severing unnecessary ties, even if they seem to lead to what appears just from today’s perspective. Anything that does not contribute to the development of power is such a redundancy. Also, living in the Wave and Acceptance helps resist temptation, when from everything that happens, one extracts that component which makes the magician stronger, and everything else is seen as perhaps not the most pleasant, but trivial and unworthy of attention. As for the relationships with the teacher, then, besides acceptance, the first place goes to OBEDIENCE: to do everything said by the teacher from KNOWLEDGE that it needs to be done and DONE.