The Problem of the “Sacred” in Pagan Magic

Monotheistic religions have developed a complex institutional framework and a rich ritual life. At the same time, pagan conceptions of the gods, as we have already discussed, differ fundamentally in that they do not separate the “divine” and the “created” into opposing poles of the cosmos. While acknowledging the transcendent reality of the Absolute, the Most High, the pagan does not seek contact with it, nor attempt to describe its properties and manifestations; instead, he directs his mystical focus toward the intermediaries of that transcendental Will – gods.

Centuries of dominance by totalitarian religions have produced a highly unflattering image of paganism as an “underdeveloped” faith, supposedly arising from an insufficient (or incorrect) understanding of the relationship between humankind and the Most High. Yet the pagan religion is no less diverse, and its theology is no less developed than Christian theology. It is simply that, like all “minorities,” paganism has been marginalized for millennia, assiduously discredited and smeared by the established churches.

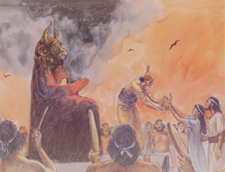

One common misconception is the image of the pagan as blindly submitting to incomprehensible “forces of nature” and trying to placate them with sacrifices. We have already discussed the meaning of sacrifice in paganism, which was not a naive attempt to “please” the gods, but an effort to repair the breach in the fabric of the worlds.

The relationship of the pagan (the conscious “enlightened” pagan) to the gods, whom he regarded as his direct ancestors, was not filled with fear or abasement. It was a mixture of reverence, respect, and love, sentiments due to the best members of the clan or family, as the deities were considered. Indeed, the pagan called, for example, the Great Goddess “Lada-Mother“, emphasizing his close, familial bond with her.

Not guided by the fear of “hell” or “posthumous retribution” dependent on the caprice of a changeable deity, as the Most High typically appears in monotheistic religions, the pagan was free to choose his path, understanding that his choice would lead to victory or defeat, which ultimately would be his victory or defeat. He did not abase himself by begging for forgiveness, but followed the warrior’s path, testing the mettle of fate and the world.

So where, then, is the place of the sacred? It turns out that the Way of the warrior, founded on responsibility, is always accompanied by a reverential awe before the manifestation of the Wisdom of the Creators of the world. The pagan honors the gods not because he fears ending up in hell, but because he sees that he and They fight on the same battlefield. He sees that the gods confront the same problems as he does, yet by virtue of their great wisdom they find (and thereby establish) effective ways to overcome those obstacles. He sees that the Myth, equally valid in eternity and at any time, is the battlefield of both himself and the gods, and this vision engenders in him respect, veneration, and admiration for their wisdom. At the same time, the pagan is not afraid to condemn the gods and even to enter into conflict with them if he believes justice is on his side and to acknowledge his own errors, thereby reconfirming the wisdom of the gods.

Sacred objects and artifacts venerated by pagans are likewise connected to particular powers, the chief aspect of which is the ability to serve as a guiding thread in the myth, helping the pagan Magus to acquire strength and authority.

Strangely enough, this sense of the “sacred” is actually far more characteristic of pagans than of adherents of monotheistic religions based on suppressing self-awareness and the subordination of the individual to the whole, of the person to the church, which robs him even of glimpses of autonomy. Looking at the world with wide-open eyes, the Magus sees in it the multicolored play of creative wills, the iridescent shifts of Powers and the play of minds that does not leave him indifferent. And in him is born the Music of the Spheres — the music of harmony, often born of a cruel but always beautiful world.

If Christians have carte blanche,

spun a tale and go to atone for sins,

then for the pagans of the North, there is a Troth where there is freedom

of action and responsibility for their

actions before themselves, before the World, the Gods of Asatru.