Theurgy — Priestly Magic

“Divine causes are not set in motion by our thoughts…[which] must be [employed]… as auxiliary causes. What truly awakens the divine are the divine signs themselves. Thus the actions of the gods stir themselves and receive no impulse for a proper manifestation of power from subordinate beings. I have discoursed on these matters at such length so that you do not suppose that all the strength of the theurgic action comes from us…“

(Iamblichus. “On the Egyptian Mysteries”)

One of the most important fields of invocatory magic is Theurgy (“divine work”, from Greek θεός, “god, deity” + Greek όργια, “rite, sacred act, sacrifice”), aimed at forging alliances between the magus and the gods in order to increase the magus’s power.

The origin of Theurgy goes back to the Chaldean and Persian magi and the ancient Egyptian priests. In both cradles of civilization — Sumer and Egypt — the art of influencing the deities was developed to an extraordinary degree. Some of the Neoplatonists practiced theurgy as well, notably Iamblichus and Proclus in the Hellenistic period, and later many European magi and mystics. In later theurgy, rituals came to be used to accomplish the merging of the personal Ego with the Will of God (the gods).

However, in the original sense accepted by ancient pagan civilizations, theurgical operations were aimed precisely at the establishing a covenant, not at the god’s absorption of the human.

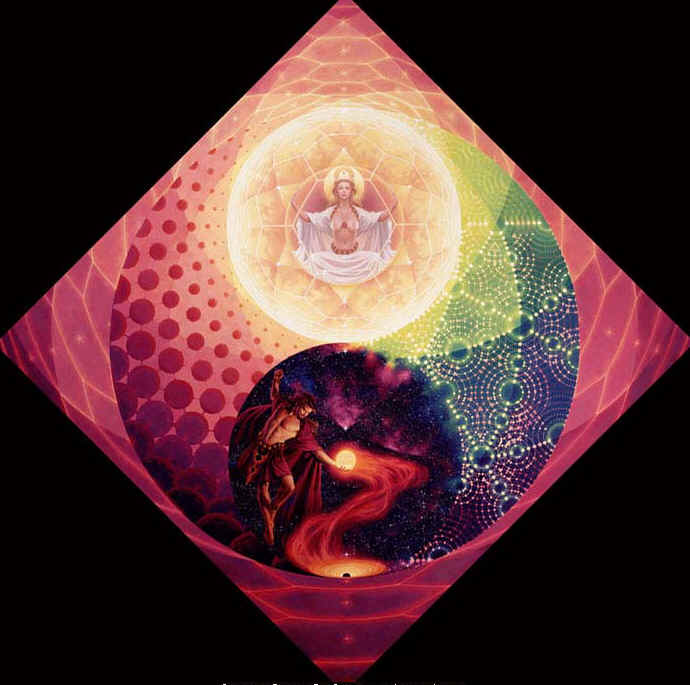

An important property of the gods, observed by ancient theurgists, was that the only way the gods’ will directly manifests in our world is through the so‑called “forces of nature“; direct personal contact between a human and a god requires creating special conditions. Theurgical work was directed at creating those conditions in which a deity could manifest not merely as a driving force, but as a personality.

In fact, in Egypt and Sumer religion was theurgy. The gods were not merely venerated; their power was actively invoked to alter reality as desired. Those who could thus “redirect” the energies of the deities formed a priestly caste, whose chief task was precisely to modify the manifestation of divine powers.

Many Egyptian magical texts do not ask the gods for help as a favor but demand it, commanding the gods to assist while invoking their own divine authority. Sometimes the gods are not even invoked; danger is simply banished, the practitioner placing themselves in God’s position:

“I am He who devised and created healing means and writings. Come to me, you who live below the earth, appear before me, great spirit! If I shall not know all that is hidden in the hearts of all Egyptians, Greeks, Syrians and Ethiopians, of all peoples and tribes, if I shall not know all that was and that will be, if I do not receive explanation about their customs, labors and life, about their names and the names of their fathers, mothers, sisters and friends, and also the names of the dead, then I will pour the blood of the black into the ear of the dog lying in a new unused vessel; I will lay this in a new cauldron and burn it together with the bones of Osiris; with a loud voice I will call him, Osiris, who was in the river three days and three nights, who was carried out into the sea by the river’s current.”

It goes without saying that magic operating through the gods could not be used for wicked ends. Hence Egyptian magic was secret, jealously guarded by the priests; they watched carefully to prevent its spread among the people. In some chapters of the Book of the Dead it is strictly forbidden to perform the rites described there in the presence of witnesses; not even the deceased’s father or son was allowed to be present. Every attempt to seize the sacred magical books or to use them for non‑religious purposes was severely punished.

One ancient papyrus contains an accusation against a shepherd who stole a sacred text and caused much misery. After listing all the crimes for which this man was responsible, the verdict states briefly and clearly: “he must die.”

In modern pagan magical tradition Theurgy is understood as the entire set of active rituals aimed at obtaining divine assistance.

Theurgy differs from theology, the study of the names and nature of the gods, by its practical nature: it is direct experience of working with the gods; and it encompasses everything that serves such cooperation.

Theurgy combines divine action and human effort. The gods do not obey humans; they act according to their own will. Yet their activity can be channeled as desired if one “comes to terms” with the gods and avoids arousing their wrath.

Invocatory rituals aimed at forging this alliance with the gods have several distinguishing features.

First, they require, more than other forms of magic, special preparation, a transformation of the practitioner — that is, Initiation. Priestly initiations are not merely a form of “caste” or a means of distinction; they are real preparation necessary so that interaction with forces beyond human capacity will not harm the practitioner; they act as a kind of protective measure. Even monotheistic religions maintained a priesthood to perform theurgical operations, which, indeed, are the “services” of worship.

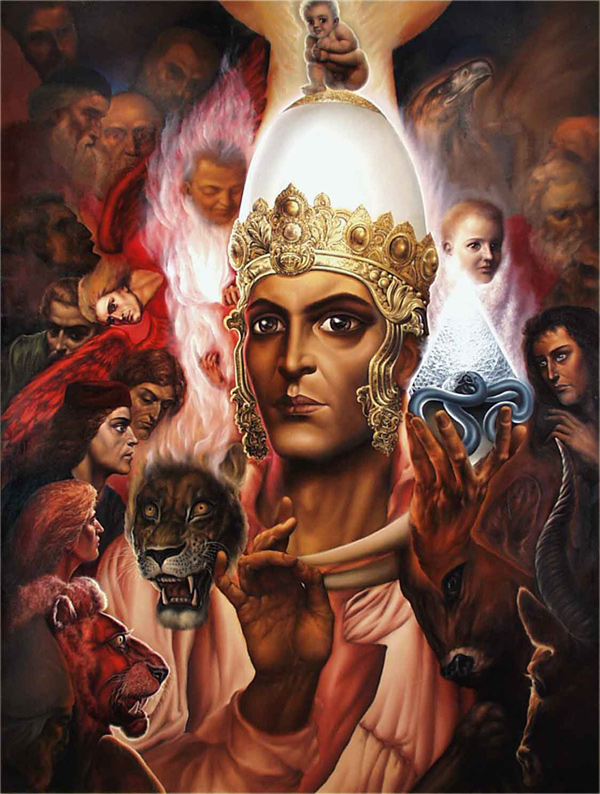

Second, as Iamblichus’s words in the epigraph show, Theurgy requires special signs, symbols and objects. One of the most important of these is the Kapi — an image or object that serves as a conduit for the deity’s presence in the theurgical act. Unlike modern, more abstract religion, invocations to pagan gods are meaningless without a material conduit for their power — the image, the Kapi.

Third, invocatory practice, especially theurgical practice, must always take into account the possibility of a deity’s “refusal” or even its wrath. Invocation is far less coercive than evocation. The priest must understand that the risk of incurring the gods’ anger is very great; therefore theurgical rites require extra care and more careful planning than in cases of evocations.

In recent times, especially under the influence of the Hermetic Order of the Golden Dawn, theurgical operations have come to be regarded as among the safest forms of magic, and in modern occult literature Theurgy is often presented as a practice aimed at personal spiritual growth and union with deity. Yet we see that this is not the case in reality. Gods do not tolerate careless dealings; their power is so great that even without hostile intent, it can traumatize the psyche and even a person’s physical body simply because of its overwhelming power.

Iamblichus warns that

“Priests, performing theurgical acts, may call these beings [the gods] to themselves, but in doing so they disturb the general order of the cosmos“

Therefore, if one takes the most general and thus the least complete and substantive definition, theurgy is the divinely ordained perfect priestly service.

It is crucial that the priest seeks to merge with the divine will and to act within its limits — that is, they influence the deity as the deity permits, not as an adversary, not as an adversary of the god or for selfish ends.

No wonder Theurgy was the “final part of priestly science” taught in the ancient mysteries. The Roman ruler Tullus Gosilius even paid with his life when he dared to partake of the sacred rites recorded in the books of the theurgic emperor Numa; at that moment he was struck down by lightning.

You can want a lot but there are few good people, and penetrating the way to the desired goal alone is impossible – unite with the gods and go towards the bright (everything that will lead many)!

“…that is, it kind of influences Divinity in the sense that God wants from a person that they influence Divinity…”. I completely agree. I am sure that Mages are not born just like that. Nature itself and the Great Spirit give Birth to Them for self-knowledge.

Dear Emercar, in your opinion, can we draw a parallel between the status of the gods in the Indian, Greek, or Nordic pantheons and the status of biblical archangels? For example, the god Shiva with the archangel Michael.

And if yes, does their correspondence not only have a similarity in status but also a similarity in essence? That is, for example, the god Shiva, the god Odin, the god Neptune, and the archangel Michael (the selection of names was intuitive) are one face, and their differences are solely defined by the traditions of the nations themselves.

I understand that this question is quite complex. If you do not have an answer to it, please just say so; a vague response won’t help here.

Very important article. Thank you very much.