Voodoo Religion

Based on the beliefs of the peoples of Dahomey (now Benin, located in the region between the modern states of Togo to the west and Nigeria to the east) and their synthesis with Catholicism in Haiti several centuries ago, a belief system emerged — Voodoo. A similar religion, Santería, based on the beliefs of the Yoruba, arose in Cuba; macumba, likewise stemming from Yoruba beliefs, appeared in Brazil.

The roots of Voodoo reach back into West Africa, from where slaves were brought to Haiti. It was the mingling of traditional beliefs of the Dahomey peoples with Catholic ideas that produced this religion. It served as a distinctive response by the enslaved to the humiliations they endured during the height of the slave trade. It is estimated that today there are roughly fifty million adherents of the Voodoo cult worldwide.

The words “vodun” and “vodu” mean “spirit” or “deity” in Fon, one of the dialects of Dahomey; according to tradition, that is where the deities dwell — the loa and spirits dwell there.

There is no central religious authority in Voodoo, which is why a common Haitian saying goes: “each Mambo and Houngan is head of their own house.” Details of rituals can readily differ from temple to temple.

Adherents of Haitian Voodoo believe in the existence of a creator God (Nsambi, Bondieu — the Good God), who does not participate directly in the lives of his creations, and of spirits (loa), who are children of the creator and are worshipped and honored as senior members of the family. After creating the world, God withdrew from humanity; yet he continues to watch closely over everything that happens on Earth and to govern the order of existence. God — Nsambi — is the true Owner of all things and all beings. He intervenes in the making of each individual. The lines on the palms and the spinal column indicate his direct influence. He governs life and death and punishes those who break his law. Nsambi does not incarnate on Earth and is not the immediate object of cultic devotion. Voodoo adherents hold that everything is permeated by the unseen force of the loa. The loa are as countless as sand on the seashore; each has its own sign, name, and purpose.

Followers of Voodoo believe that the objects serving a loa extend and express that loa. The loa are highly active in the world and often possess the faithful during an entire ritual. Only special people — such as certain sorcerers, houngans, and priestesses, mambos — can communicate directly with the loa. During a rite, sacrifices and ritual dances are performed; then the houngan falls into trance and entreats the loa for help and protection in worldly affairs and for prosperity. If the loa are pleased with the offerings and the rite has been carried out correctly, success is beyond doubt.

According to Voodoo belief, several souls reside in a person. Before birth and after death one becomes a Guinean angel. In addition, there lives within a person the ambassador of God — conscience. One soul, the gros-bon-ange, the “big good angel,” endows a person with a particular individuality. Even before birth — before “arrival on Earth” — each of us was such an angel. After death a person becomes an angel again and returns to the ancestors in “Guinea.” This land has nothing to do with the three African Guineas; it is a blessed realm, a land of dreams. In moments of trance the “big good angel” flies out of the person’s body and is replaced by a god. The “angel” itself may, in time, become a god as it learns and acquires wisdom. Another soul, the ti-bon-ange, the “little good angel,” is our conscience, a kind of personal guardian angel. It is the spark planted in us by God. It glows while we live and after our death it returns to God in the heavens. Voodoo practitioners believe in reincarnation, using the term “Joto.” The spirit of the “reincarnated” ancestor is the Joto. Joto is the soul transmitted from an Ancestor, whose “representative” the person is, and who watches over that individual. Joto is the Ancestor whose life-flow animates the child. He is mentioned as Se-Joto or Se mekokanto. He is the one who presents to the Creator the clay from which the body of the newcomer will be “shaped.” He is the force, the life and spiritual energy that models and directs a person’s existence; Se (Protector) is given to the person. In principle the child does not receive the name of their Joto. One may, however, address the Joto by that name from time to time to remind the Joto. That name may prevail if the person is initiated into the cult of their Joto. In that case, the Joto’s name becomes the person’s effective name within the religion. The individual soul of a Joto does not incarnate in its “protégé” but transmits to the latter their social status and role.

Haitian Voodoo has two principal pantheons — Rada and Petro. Rada (the Creole term for Allada) is a pantheon originating in Dahomey. Petro is a pantheon with roots in the Congo (contrary to widespread belief, the Petro pantheon of Voodoo is by no means composed solely of spirits of Congolese origin).

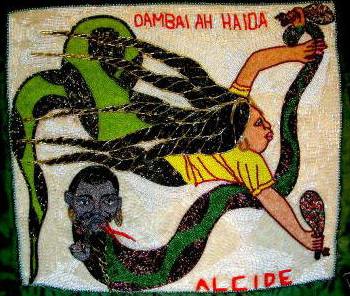

Voodoo honors the goddess of love, Erzulie, and the great Serpent Damballa Wedo. This Serpent is a principal and indispensable element in all Voodoo mysteries, for he is the beginning and the end of all things; the Ocean of Eternity that encompasses the material world on all sides; the boundless expanse from which all emerged and to which all will sooner or later return. Damballa is the source of Power and the locus of all the loa. Damballa may represent both benevolent and malignant Power (depending on the one who calls him).

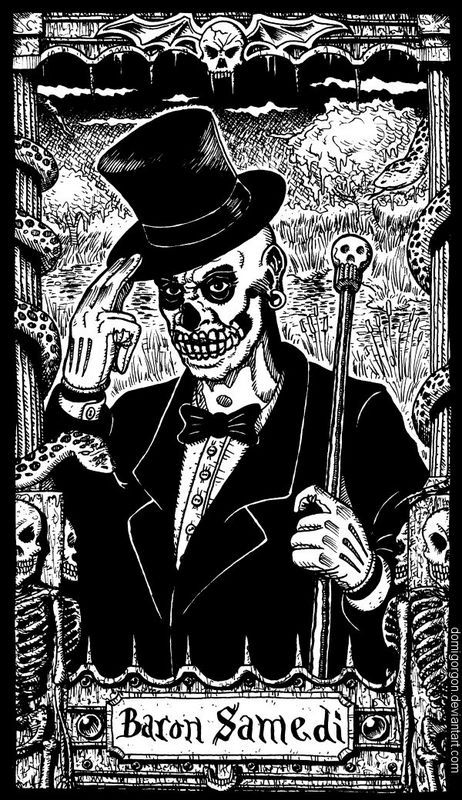

Another well-known loa is Baron Samedi, or Gede. He is the terrible god of the realm of the dead. He is known to wear a tailcoat and smoke a pipe, so these props are prepared in advance. Gede also loves rum, especially if pods of hot pepper are thrown into it. A victim chosen by Gede may fling themselves at the bottle and drain it at a single swallow.

Voodoo has well-defined views concerning the “dark” side of the loa and of people. Sorcerers who use black magic are called bokors; they are organized into secret societies. They may curse a person using a wax doll, or they may reanimate a corpse completely subjugating it, or bewitch an enemy and thereby cause them mortal terror. The darker side of Voodoo rites became widely known in the civilized world because of “zombies.” American pharmaceutical companies took an interest in a powder by which a person could be brought into a controllable, zombie-like state. Dozens of people allegedly treated with a substance unknown to science were officially examined; the substance reportedly blocked certain regions of the brain responsible for vital functions (such as heartbeat, respiration, circulation), while strangely leaving the mind intact. The result was that a person seemed to die and then, after some time, revive, partially or completely without memory of their previous life. Rumor has it that black sorcerers in Voodoo can create for themselves or for another as many doubles as they wish, many likenesses or “imprints.” A soul can be alternately lodged in any of the created likenesses, while the others act as zombies, obeying the will of their master, who is impossible to find among the crowd of doubles. Another method of destroying a person through magic is to send upon them spirits of death. The victim of such an attack begins to fall ill, to waste away and to pine. Sometimes the victim finds a more powerful sorcerer who, for money, exorcises the evil death spirit that has entered the unfortunate. But it also happens that the sorcerer who sent the spirits is the one who later expels them.

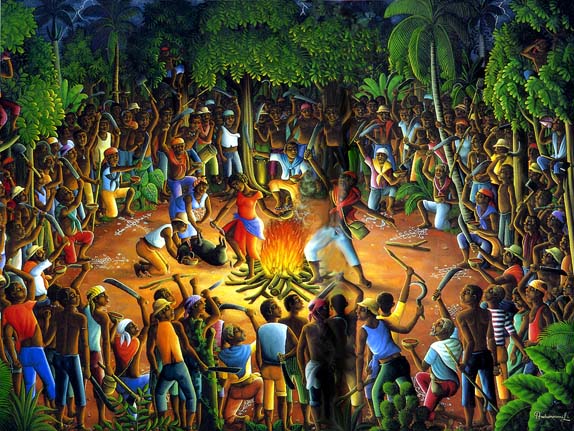

As a sanctuary, Voodoo practitioners choose an ordinary dwelling (hounfour — a sanctuary). Only some houngans hang drapo on cult buildings — motley flags embroidered with sequins and colored threads that indicate ceremonies are held here. Voodoo religious ceremonies often take place at night in the depths of humid tropical forests.

As a sanctuary, Voodoo practitioners choose an ordinary dwelling (hounfour — a sanctuary). Only some houngans hang drapo on cult buildings — motley flags embroidered with sequins and colored threads that indicate ceremonies are held here. Voodoo religious ceremonies often take place at night in the depths of humid tropical forests.

The main elements of Voodoo ceremonies are the mitan (the pole — the road of the gods) and black candles. A ritual always begins with driving a long staff into the ground, serving as a kind of foundation for the symbolic representation of Damballa. Three drummers, each keeping a distinct rhythm, announce the opening of the ceremony. Usually at the start of the rite a prayer song is sung to the loa Legba: “Papa Legba, open the gates. Papa Legba, open the gates and let me pass. Open the gates so that I may give thanks to the loa.” The loa Legba, or Papa Legba, is conceived in Voodoo as the intermediary between the other gods and the priests — houngans and mambos — who, in turn, convey the will of the people to him through ritual dances and songs. Legba is the guardian of the gates to the otherworld. Without his help the gates cannot be opened, and one cannot reach the demons and spirits. Therefore, from the very beginning of the ceremony they appeal to him: may the gates be flung wide. Those possessed by Legba are immediately obvious. For he himself is an old cripple; likewise those he seizes lose the ability to move normally. They seem paralyzed; some lie rigidly on the ground, unable to stir.

Dancing around the pole, the mambo, together with her assistant (ounsi) and her helper (la plasom), create, with a stream of water from a jug, a magic circle around the pole in honor of Papa Legba and the household guardian Ogun Ferreya, to drive away evil spirits from themselves and those present, spirits which some observers identify with Christian saints. The dances are accompanied by drums, whose monotonous sound leads those present into trance. From the vessel of sacrificial blood, or directly from the bleeding, decapitated animal or bird, the priests anoint the faces of all participants in the gathering. Sometimes the decapitation of a chicken brought as an offering is performed by biting off its head amid a frenzied dance, in a state of ecstasy. All this takes place around a blazing fire beside which stands a box or container holding the main object of veneration — a snake (the symbol of Damballa).

Thus, Voodoo is not merely a collection of superstitions and magical practices; it is a developed religion with its own metaphysics, pantheon, and cult, which nevertheless incorporates far more magical and even black-magical approaches than any other modern religion.

Enmerkar, how to neutralize the use of black magic performed through voodoo?