The Honorius Tradition

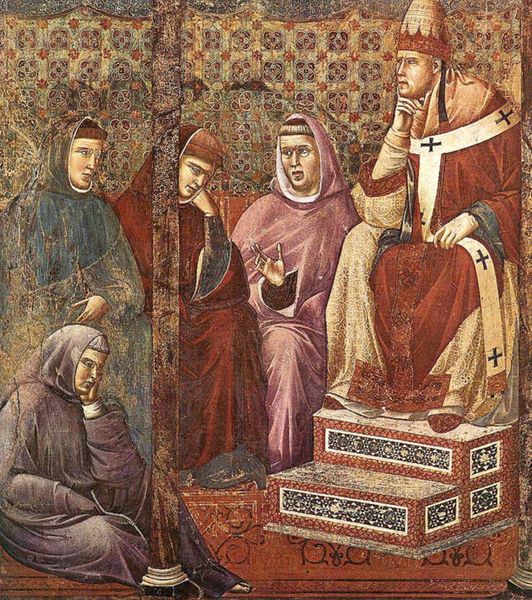

In 1216 the papal throne was occupied by a practitioner of the magical arts who took the name Honorius III (Latin: Honorius PP. III; born Cencio Savelli, 1148, Rome — died 18 March 1227, Rome). He was Pope from 18 July 1216 to 18 March 1227.

Under his patronage, the Inquisition developed rapidly. The Order of St. Dominic was established, and within it additional bodies were formed whose main purpose was to suppress heresy and support of the Inquisition. This order became the stronghold and executive arm of the Inquisition. It was only after the founding of the Dominicans that the Inquisition, now organized as an institution and enjoying powerful backing, began to expand rapidly.

After his death Honorius was canonised by the Catholic Church.

The genuine writings of Pope Honorius have been published in two large volumes and contain not the slightest hint of magic, let alone goetic magic.

Nevertheless, contemporaries regarded Pope Honorius as a powerful sorcerer who allegedly instigated persecution of witches to eliminate rivals.

Honorius’s affinity for magic is supported only indirectly by his patronage of the astrologer and Magus Michael Scot. Around 1224 Honorius III proposed Scot as archbishop of Cashel in Ireland. Later the pope recommended Scot to the English king Henry III (1216–1272). Moreover, according to a papal bull of Honorius III, the study of medicine, physics and other natural sciences was forbidden under threat of excommunication. Honorius strictly prohibited all clerics from practising medicine in any form, which effectively barred educated people from practising surgery.

It is therefore unsurprising that, alongside the Solomonic cycle of Grimoires, a magical tradition arose that traced its origins to Pope Honorius.

Thus the Dominican monk and inquisitor Nicholas Eymericus (1320–1399) wrote that he personally seized the book “The Treasure of Black Magic of the Magus Honorius” and later publicly burned it. No other Grimoires provoked as much outrage in the Catholic Church as the books attributed to Honorius.

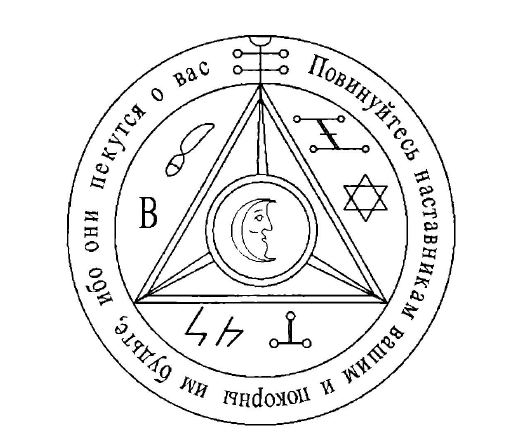

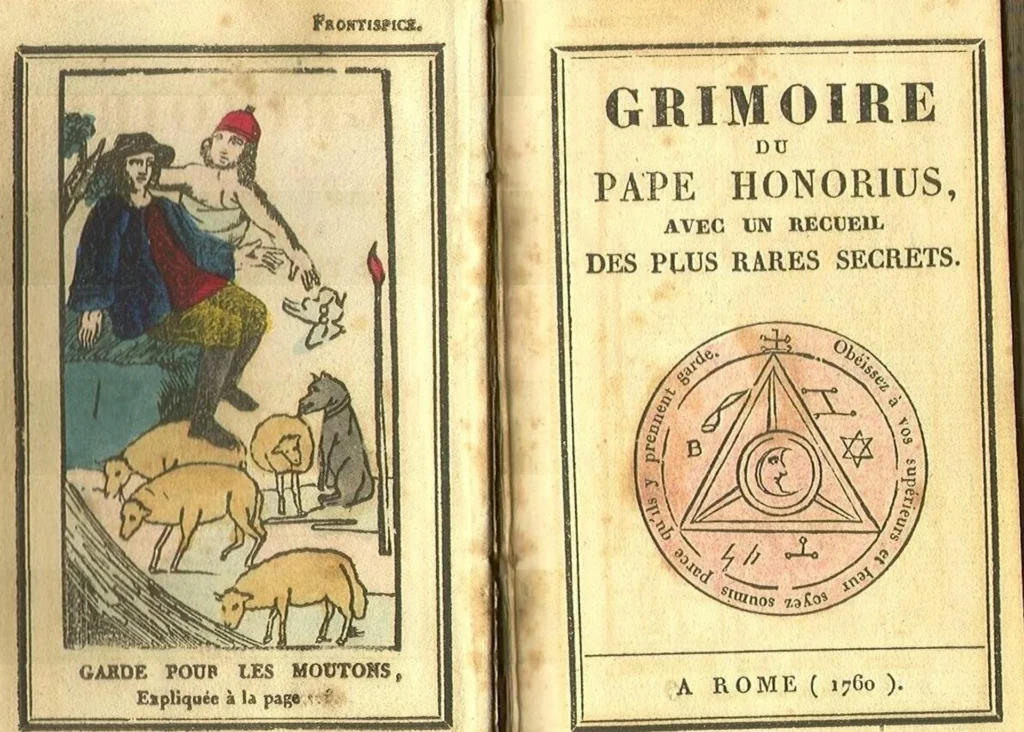

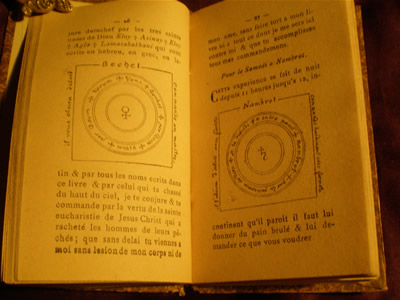

The principal work attributed to Honorius is the “Grimoire of Honorius.” The “Manuscript of Honorius” was first printed in Rome between 1628 and 1671. No manuscripts of this text have survived, and the first printed edition appeared only in the 17th century in France. According to A. Waite, this book, attributed to the Roman Pope, is a malicious and, in a certain sense, skilful deception whose purpose was to tarnish the Catholic Church.

At the same time, the editor of that edition referred to an earlier edition dated 1529. Interestingly, according to the “Grimoire of Honorius,” the person who summons demons must be a Catholic priest.

He must observe a fast, confess, and spend time in the church at the altar; he must celebrate Mass and recite prayers in keeping with Catholic ritual.

In other words, this “Grimoire” attempts to harness the Catholic egregore in support of goetic rituals.

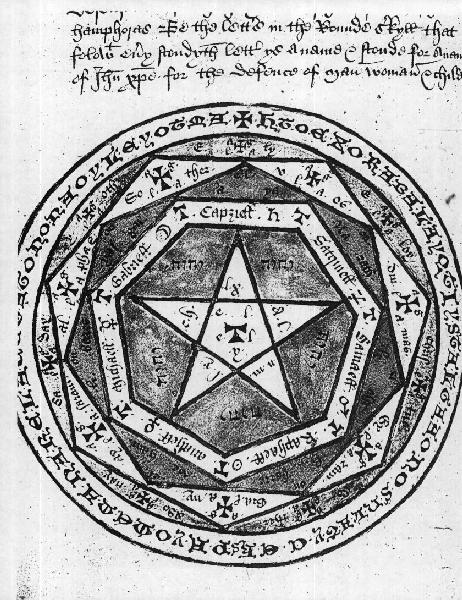

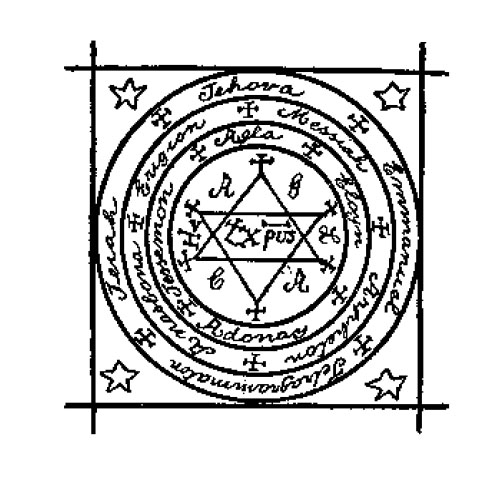

Overall, the “Grimoire” is built on the traditional structure: it contains prayers and invocations, rules for constructing and conjuring the magic circle, and refers to the magical ritual the “Great Work.”

Several versions of the Grimoire are known, differing in some details — a German version (1846) and two French ones (1800 and 1860). The most complete is the 1800 edition, which was used and quoted by Eliphas Levi.

Alongside entirely “respectable” conjurations and prayers, the Grimoire also contains elements of black magic — instructions for sacrificing a lamb and ritually burying it, the hide of which is then used in the Ritual.

At the same time the Grimoire is precisely a “technical” manual: it does not say which spirits should be summoned or for what purpose, nor does it examine their character or particular powers. Its focus is solely on the conjurations and prayers that should compel a spirit to appear to the practitioner.

Some of the names used in the Grimoire — for example, the Kings of the Cardinal Points — are traditional in Solomonic magic, and the invocations of demonic rulers, which are carried out on different days of the week, are accompanied only by the demand to “answer truthfully to all I ask, and do me no harm.”

At the same time, the names of demons differ from those found in the “Solomonic” tradition; only Lucifer and Astaroth are common, while other “princes of hell” are not mentioned in other Grimoires.

Attached to the “Grimoire” are the “Rarest Secrets of the Magical Art” popular in the 18th century, loosely connected to the main text and devoted to love magic, winning at games, and the like.

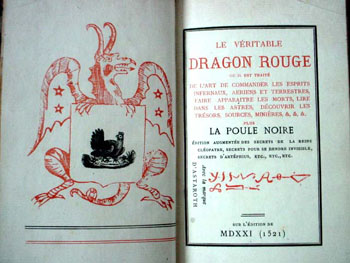

Other Grimoires are also attributed to Honorius, in particular the “Little Albert” and the “Red Dragon.”

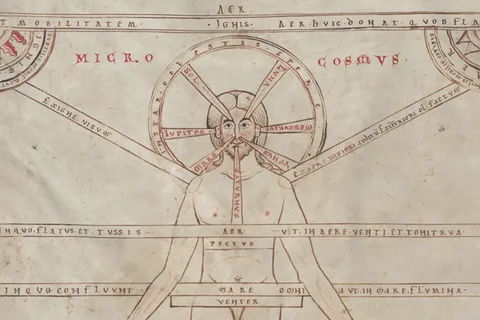

Some light on the mention of Honorius may be shed by another grimoire of the Honorius Tradition — Liber sacratus or Liber sacer or Liber juratus, as it is also called in some manuscripts, often referred to as the “Sworn Book of Honorius.” It is this book — the first in the cycle of Honorius’ grimoires — that gave its name to the whole corpus.

The preface appended to it in 14th-century Latin manuscripts — one of which once belonged to Ben Jonson — reports that, under the influence of an evil spirit, the Pope and the cardinals issued a decree whose aim was to root out the magical art completely and condemn all Magi to death. The grounds for this decree were said to be that Magi and necromancers harmed people by violating the precepts of the holy Mother Church, by summoning and sacrificing to demons, and by luring the unwary into curses with their beguiling illusions. The Magi hotly denied these accusations as inspired by the envy and greed of the devil, who wished to retain a monopoly on the performance of such wonders.

The Magi declared that an evil or impious person could not master the magical art, asserting that spirits would submit against their will only to a pure person. Furthermore, the Magi claimed that by their art they had been warned of impending repressions in advance.

But they nevertheless doubted whether they should summon spirits for assistance, lest these spirits use the opportunity to destroy the human race. Instead, an assembly of 89 masters from Naples, Athens and Toledo chose Honorius, son of Euclid, Master of Thebes, to collect all the magical books into one edition of 93 chapters, which would be much more convenient to keep and conceal.

For this purpose they resolved to summon Demons and to obtain directly from them the precise details of invocations and conjurations.

And because prelates and princes had taken to burning their books and destroying magical schools, the practitioners of this art swore that whoever possessed this book should not hand it on to anyone until he was on his deathbed. Moreover, there should never be more than three copies in existence at any one time; they were never to be given to a woman, to a minor, or to anyone who could not prove his devotion. Each new recipient of the sacred edition was also to take this oath. Hence the name Liber Juratus, or the Sworn Book. Its other names, Sacer or Sacratus, refer either to the sacred names of God that make up most of the text, or to its dedication to the angels. After this preface, which, like all magical art, is more rhetorical than factual, the work unsurprisingly opens with the declaration, “in the name of the almighty Lord and Jesus Christ, the only and true God, I, Honorius, thus placed Solomon’s works in my book.” Later Honorius repeats that he follows in the footsteps of Solomon, whom he often quotes and to whom he frequently refers.

Explicit of the Sworn Book — unusually long and high-flown — defines the aims of the edition: “Such are the purposes of the book of the rational soul’s life, called Liber sacer or the Book of Angels or Liber juratus, which Honorius, Master of Thebes, created. This is the book by which one can behold God in earthly life. This is the book by which anyone may be saved and without doubt brought to eternal life. This is the book by which one may see Hell and Purgatory without dying. This is the book by which any creature may be subdued, except the nine angelic orders. This is the book by which one may learn all the sciences. This is the book whereby the weakest being may prevail and subdue the strongest entities. This is the book which no one but a Christian may use, and if anyone attempts to do so his efforts shall be in vain. This is the book that is a greater joy than any other joy given by God, the most exclusive of communions. This is the book by which one may transform material and visible nature, and tame the incorporeal and invisible. This is the book by which one may obtain countless treasures. And by means of it many other things may be made, too many to tell of in the time allotted, and therefore it is rightly called the Holy Book.”

Thus we see that the magical tradition knew two figures named Honorius — the Pope and the Master of Thebes. Whether this is true, or a forgery — whether the Pope’s works were attributed to a certain Magus, or whether, conversely, the Magus’ works were sanctified by the Pope’s name — is not entirely clear.

It should be added that practicing magicians (including Crowley, who was very fond of the conjurations from the “Grimoire of Honorius“) testify to the high effectiveness of the rituals laid out in the Grimoire of Honorius, and whoever its author may have been, the significance of this Grimoire in the magical tradition is comparable only to the “Lemegeton.”

I apologize, but why did you associate Gonoria with OHS? Are there any sources pointing to this? Where did this OHS even come from (the legend on their website doesn’t seem like a convincing source to me, but this topic is extremely interesting and important for me for some reasons).

Honestly, I didn’t even know that this name is currently used for an existing virtual organization. In the 12th-13th centuries, such a name belonged to a Catholic Order, which had nothing in common with modern ‘necromancers,’ and specialized in posthumous accompaniment (similar to ‘Bardo Thodol’).

Interesting… and sad times of the ‘witch hunts’

Very very interesting. Thank you