The Golden-Haired Apollo

Among the many solar deities one attracts attention by an extreme ambiguity that enfolds all the characteristics of the Sun itself — Apollo. No people, apart from the Greeks — and not the early, luminous Greeks but the later ones who had come into contact with Egypt and Chaldea and been tempered by their wisdom — stamped so precisely the Spirit of the Sun who illuminates, mercilessly reveals secrets, scorches, and is self-sufficient in his perfection.

Slavic solar deities are milder, and even Yarilo, in all his frenzy, is creative and benevolent; even Khors — the noon sun — does not possess the radiant ruthlessness of Apollo. Having absorbed traits of the formidable Shamash, who took Utu’s place in the Mesopotamian pantheon, the triumphant power of Horus and the gentleness of the Greek Phoebus, the later image of Apollo differs considerably from the original.

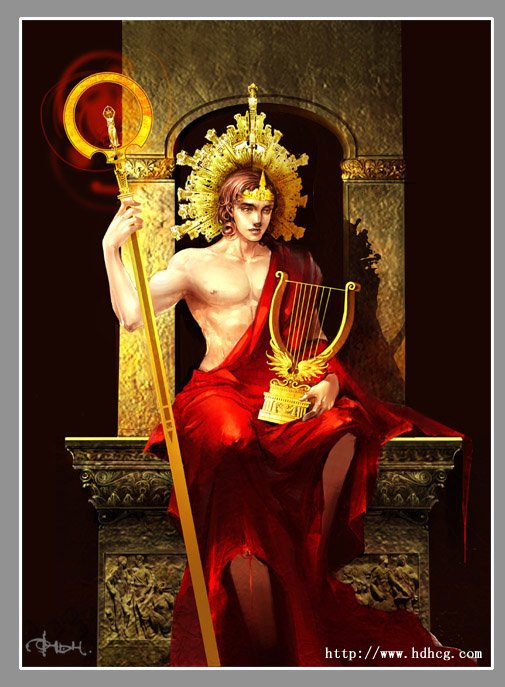

Apollo is one of the most ancient gods of Greece. His name is thought to derive from the Greek àπελάω, “to drive away,” or from απέλλα, “assembly.” His name does not appear in the Cretan-Mycenaean texts. It is believed that Apollo was originally a pre-Greek, probably Anatolian, deity. His deep archaic quality shows in his close association and even identification with the plant and animal worlds. In myths of an earlier period, Apollo is prone to rash acts, quick to execute vengeance; in later myths he becomes personified reason, harmony, and creation, which nevertheless exude a cold perfection. Apollo is the second most important god in the Greek pantheon, inferior only to Zeus. He is the god of the sun, of the arts (especially music), of prophecy and archery. He is lawgiver and punisher; patron of medicine, yet also able to send disease; protector of shepherds.

The cult of Apollo was widespread throughout Greece; temples housing Apollo’s oracles existed on Delos, in Didyma, Claros, Abai, on the Peloponnese and elsewhere, but the principal centre of Apollo’s worship was the Delphic temple with its oracle, where the priestess of Apollo — the Pythia — sat on the tripod and gave prophecies. Festivals were held in Apollo’s honour at Delphi (theophanies, theoxenias, the Pythian Games). All months of the year except three winter months were dedicated to Apollo at Delphi. From the Greek colonies in Italy, the cult of Apollo spread to Rome, where this god assumed one of the foremost places in religion and mythology. Emperor Augustus declared Apollo his patron and instituted century games in his honour; the Temple of Apollo near the Palatine was among the richest in Rome. In Arcadia, Apollo was worshipped as a ram.

Myths about Apollo are well known. He is the son of the goddess Leto and of Zeus, the twin brother of Artemis, and the grandson of the Titans Coeus and Phoebe. He was born on the island of Delos (Asteria) (Greek δηλόω — “I reveal”), where his mother Leto came by chance, pursued by the jealous Hera, who forbade her to step upon firm land. When Apollo was born, the whole island of Delos was flooded with streams of sunlight. Apollo was born on the seventh day of the month, prematurely at seven months, embodying the symbolic field of the heptads. When he was born, swans from the Pactolus performed seven circles above Delos and sang for the newborn god. Leto did not nurse him: Themis fed him with nectar and ambrosia. Hephaestus gave arrows to both him and Artemis.

Apollo’s epithets are numerous and varied: Paean and Peon (“Reliever of maladies”), Musagetes (leader of the Muses), Moiragetes (“Driver of fate”), Phoebus (“Radiant” — indicating purity, brilliance and prophecy), Sminthian (Mouse), Alexikakos (“Averter of Evil”), Apotropaeus (“Averter”), Prostates (“Protector”), Acesius (“Healer”), Nomius (“Shepherd”), Daphnaeus (“Laurel”), Drimas (“Oak”), Lycean (“Wolfish”), Letoid (from his mother’s name), Epikurios (“Benefactor”).

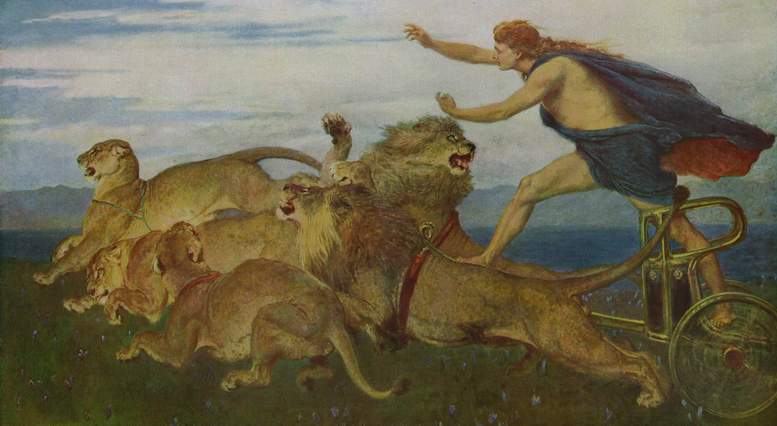

Plants and animals associated with him include laurel, oak, cypress, palm, olive; wolf, raven, swan, hawk, serpent, mouse, ram, and grasshopper. Apollo’s attributes are a silver bow and golden arrows, a golden kithara (hence his byname Kitharet — “player of the kithara”) or a lyre.

Well known are Apollo’s deeds. The serpent-slaying aspect of this god is the most famous. Apollo matured early and, still very young, killed the serpent Python (Delphinian), which had pursued Leto and devastated the vicinity of Delphi. At Delphi, on the spot where once the oracle of Gaia and Themis stood, Apollo founded his own oracle. Apollo also struck down with his arrows the giant Tityus, who tried to offend Leto, the cyclopes who forged Zeus’s thunderbolts, and he took part in the Olympians’ battles with the Titans and the Giants. Even in these myths Apollo’s punitive nature is evident.

Apollo’s deadly arrows and those of Artemis bring sudden death to the elderly and sometimes strike without any apparent cause. In the Trojan War, Apollo the Bowman helps the Trojans, and his arrows bring plague to the Achaeans’ camp for nine days; he invisibly participates in the killing of Patroclus by Hector and of Achilles by Paris. Together with his sister Artemis (incidentally, it is quite probable that Apollo and Artemis were originally different aspects of a single hermaphroditic deity — there is much evidence for this, though that theme lies beyond the scope of the present discussion) they destroy the children of Niobe. In a musical contest, Apollo defeats the satyr Marsyas and, enraged by his presumption, flays him. This is a very characteristic trait of the golden-haired god: once Apollo triumphs over a rival, the god, knowing no mercy, may coolly strip him of his skin. When the restrained, reasonable Apollo gives rein to emotion, those emotions prove highly irrational. He becomes a poisonous serpent, sinking into his victim his venomous fangs.

Like other youthful gods, Apollo refused to marry. He is not prone to casual affairs and is usually too absorbed in the goal before him to be distracted by women. His first love was Daphne — yet, because of Eros, love did not bring happiness to the sun god. Apollo mocked Eros, asserting that the god of love could not shoot straight. Angered, the god of love shot a golden arrow of desire into Apollo’s heart and a leaden arrow of aversion into Daphne’s. Consumed by passion, Apollo pursued Daphne, and when he was about to overtake her she cried out to her father, the river god, who turned her into a laurel tree. Yet Apollo’s love for Daphne did not die. The laurel became his sacred tree, and a wreath of its branches adorned the god’s head.

In the form of a dog, he lay with the daughter of Antenor; in the form of a tortoise and of a serpent — with Dryope.

The most famous woman to spurn Apollo’s love and pay the price was Cassandra. Cassandra, daughter of the Trojan king Priam and queen Hecuba, received from Apollo the art of prophecy in exchange for a promise to yield to him. Cassandra gave her word but did not keep it. Apollo could not take the gift of prophecy from her, but in revenge, he made it so that no one would believe her prophecies. From the beginning of the Trojan War, Cassandra experienced visions of the disasters threatening the city, but the Trojans dismissed the prophetess as mad.

The Sibyl (whose name is used for sibylline prophetesses) likewise accepted Apollo’s gift of prophecy and rejected him as a lover. Apollo harboured the erroneous belief that love could be obtained in exchange for a favour.

Once Apollo became so enamoured of a youth named Hyacinthus, son of a Spartan king, he neglected Delphi entirely and spent all his time with him. During a discus-throwing contest, Apollo’s discus rebounded off a stone, struck Hyacinthus and killed the youth. Grieving the death of his beloved, Apollo swore that Hyacinthus would be remembered forever. A flower sprang from the youth’s blood, which still bears his name.

The functions of Apollo are contradictory. On the one hand, he is leader of the Muses, Musagetes, patron of the arts, poetry and music. Yet with his arrows, he brings death, destruction and plague (for example, at the opening of the Iliad). There are mentions that Apollo would gladly hunt with his sister, and that this hunt was terrible and merciless. His outward image is noble: his garments emit a magical light and scent, he plays an elegant instrument that produces a tender, measured sound. Beautiful as a white swan, Apollo could be cruel and deadly like a wolf. Hence he was also called “Wolfish” and was offered in sacrifice the animals preferred by these wolves. In one of the temples of Leto’s son stood a bronze image of Apollo in the form of a wolf.

Apollo constantly opposed heroes. He refused to give a prophecy to Heracles when the hero appealed to the Delphic oracle. He opposed Achilles, the most revered and celebrated of the Greek heroes. Achilles died when an arrow struck his heel — the only part not washed in the Styx. According to different versions, he was slain by Apollo himself — either in the guise of Paris or in person. In any case, it was not a heroic face-to-face duel but a shot from a distance.

Apollo values prudence, avoids physical danger, does not yield to emotion and prefers the role of observer. When a sharp emotional conflict arises, he immediately withdraws: “the matter is not worth fighting over.” That is exactly how he behaved during the Trojan War when Poseidon challenged him.

Thus Apollo is the principle of Order brought to perfection and even surpassed. Order, when unbalanced by spontaneity, becomes cold fetters for spirit and creativity, and sometimes even deadly. As Nietzsche says,

“What Apollo wants in bringing distinct beings to rest is to separate them from one another, and in doing so he constantly, again and again, reminds them of these boundaries as sacred world-laws…”

In Apollo’s view, there is no and cannot be any absolute mystery; there will come a day, and all secrets will fall beneath the all-subduing ray of absolute truth. Approaching Apollo’s blazing light dries the soul and robs it of its fluidity. Inner significance gives way to formal meaning, and the striving for the harmony of individual living unities is displaced by the pursuit of an illusory neatness of abstract relations. Apollo’s crystalline clarity degenerates into living ossification, into the death of the whole being, producing contempt for everything and an unsatisfying pride which, when it seizes one, gives way to gloomy despair. The highest light loses its creative power and becomes merely destructive, an all-devouring fire.

Enmerkar, do you agree that Apollo corresponds to Lucifer and Veles?

I wouldn’t say ‘corresponds’, but in my opinion, Apollo and Lucifer express the same underlying principle; however, Apollo represents the ‘upper’ section of the principle of differentiation, while Lucifer represents the ‘lower’ section of the same principle. As for Veles, he does not differentiate the world; he maintains the separateness of objects, not allowing them to merge into one or completely divide. So he expresses another, essentially different, force, more synthetic in nature.

What an interesting analysis of Apollo’s personality. It was extremely interesting. Thank you! Because apart from Kuna, little can be found.

Along with destructive actions, Apollo also possesses healing abilities. He is a doctor, assistant, protector against evil and diseases, who stopped the plague during the Peloponnesian War. The first to begin healing eyes.

It’s interesting that the Hippocratic oath begins with the words: ‘I swear by Apollo the physician…’