The Gods of Egypt

The mythological system of Ancient Egypt has, of course, achieved an astonishing degree of coherence and refinement both in theoretical terms and in practical, theurgical terms.

For the inhabitants of ancient Egypt, the gods were, on the one hand, transcendent cosmic forces that ensured the existence of the world and people, situated in complex relationships with one another and with their creations; and on the other hand, a thoroughly practical object of influence, of operation and sometimes even coercion.

This very conception has been inherited by contemporary Magical Traditions, for which deities are paradoxically both transcendent and immanent, sublime objects of veneration, and points of application for governing activity.

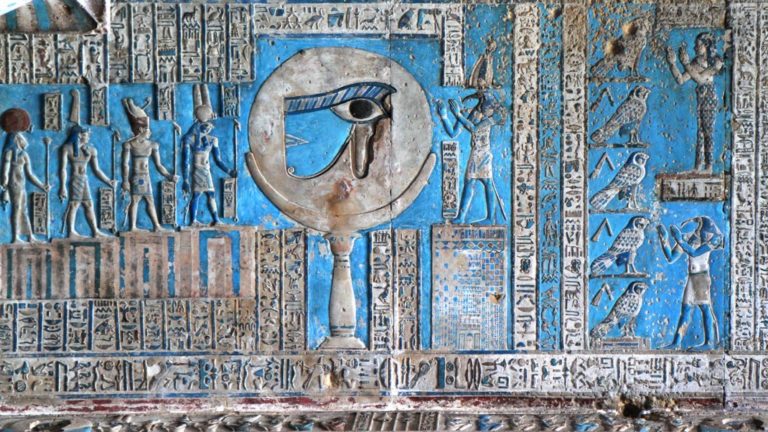

It is no accident that modern Orders so often and readily use specifically ancient-Egyptian imagery to activate higher Matrices — “Adoption of Divine Forms.” The founders and Leaders of these Orders have repeatedly found that even after more than two millennia, the Matrices of the gods of the Black Land still retain their vitality, creative activity, and transformational potential.

The inhabitants of the Nile Valley were able to detect and record in their minds, above all, exceptional precision in depicting the function of the Matrices, their nature and their mutual relations. Perhaps no other mythological system examined in such detail the mutual transitions, the “intersections” of their natures and functions. Indeed, describing, for example, Benu, Sokar and Khnum as the ba of Osiris or Hapi as the ba of Ra and Ptah, the Egyptians did not deny these deities’ autonomy, yet they shifted consideration of their interrelations to an energetic plane.

It is precisely this attitude that leads many to speak of “Egyptian monotheism” or “pantheism,” since the energies of the gods flow into one another, transform into one another, manifest in one another, and therefore can readily be presented as a unity.

Nevertheless, such a view somewhat simplifies the matter. For the Egyptians, divinity was an attribute of the cosmos; it manifested in different gods (and kings) in their various aspects, yet it had no ‘ideal bearer,’ a ‘God of Gods’ figure (although different figures could claim that function).

In its internal logic, this outlook is closer to the Buddhist notion than to monotheism, the Buddhist notion of “Emptiness,” which manifests as a multiplicity of “Forms.”

Thus each Egyptian god is a “Voice of Emptiness” — an eternal yet ever-changing energy manifesting in diverse forms.

Of course, this conception does not negate the reality of the gods as figures, agents, and personalities with their characteristic traits and attributes; it complements, expands, and deepens that reality. It is precisely for this reason that the Egyptian description of divine powers is closest to the magical worldview, a vision of the world as a space of interactions, manifestations, and energies rather than of objects.

For the magus who wishes to employ the Egyptian myth as a theurgical foundation, it is vital to grasp this energetic component of Egyptian mythology because understanding it opens the possibility of establishing contact with the Solar transformational Matrices, awakening them in the mind, and for using their potential to harmonize the world and the mind.

Leave a Reply