The Legend of the Sword of Nergal

As discussed, artifacts that have affected (at least psychologically) the course of human history — the Spear of Destiny and the Holy Grail.

However, these artifacts, though the best known, are by no means the only objects cloaked in mystery and legend. Another such item is the great Sword of Nergal.

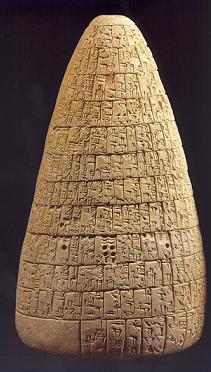

Legends date its appearance to the 24th century B.C., when kingship in Mesopotamia was centered in Lagash. At that time the ruler (ensi) of Lagash was Enmetena (c. 2360–2340 B.C.), son of Enannatum I and nephew of Eannatum. His name meant “Ruler by his destiny,” and he received it because, contrary to customary practice, he did not belong to the priestly class. Enmetena took an active part in constructing canals not only in his native Lagash but beyond its borders. He enjoyed enormous prestige among the rulers of Sumer; his sculptures stood in the temples of Nippur (the spiritual capital of Sumer) and Uruk. Enmetena conducted a protracted war with the city of Umma over the fertile region of Gueden, taken from the Ummans by Enmetena’s uncle Eannatum. The Ummans, having failed to pay the tribute promised to Eannatum, destroyed the boundary stones and occupied the disputed territory on the field of Gueden. War broke out between Eannatum I (Enmetena’s father) and Ur-Lumma, son of Enakale, the lugal of Umma. Enmetena continued this war after his father. The previous border was restored, but the citizens of Umma suffered no punishment: not only were they not required to pay debts or tribute, they were not obliged to supply water to the war-ravaged agricultural districts. Having dealt with Ur-Lumma, Enmetena installed the Balamed priest Ilia to rule in Umma. But even with him he had conflicts, since the priestly authority traditional in Sumer was not accustomed to submitting to a warrior ensi. All the more offensive was Enmetena’s decision regarding the appointment of priests.

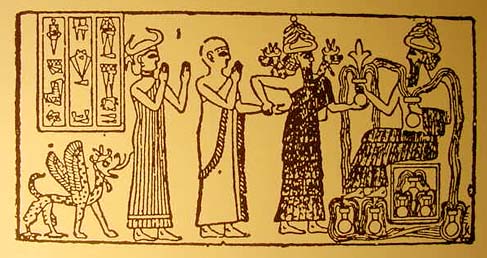

The second most powerful person in Lagash under Enmetena, and in effect his co-ruler, was the high priest of the god Ningirsu (and one of his aspects — Nergal; the god of war and violent order had two aspects: Ningirsu and wrathful Nergal; Ningirsu was venerated in Lagash, Nergal in Kuta), Dudu. This priest had originally been the ruler of Uruk, but after the treaty and the transfer of kingship to Lagash, Lugal-kin-ingenesh-dudu, priest of Inanna, became also priest of Ningirsu, Dudu. Dudu even composed inscriptions in his own name; some documents bear double dating, by the names of Enmetena and Dudu.

Enmetena carried out a series of reforms aimed at easing the burden of levies and corvée labor, as well as debts and arrears that weighed on the poorest groups, together with certain legislative reforms. Naturally, this also incurred the wrath of the priests, since it reduced their incomes.

Enmetena reigned for about twenty years. In documents from Enmetena’s lifetime a prominent place is occupied by his son Luma-tur or Humma-Banda (the name is read variously, but it means “Junior (or Young) Luma (Huma).” Luma or Huma was a byname of Eannatum). This son was Enmetena’s firstborn, but, not being a priest like his father, he would, upon accession, have continued to curtail the priests’ privileges; therefore the priestly elite could not allow his enthronement. However, simply killing the ruler or even his son was impossible for the discontented priests. Kingship was a divine category and could not simply be seized — for that one required the gods’ sanction.

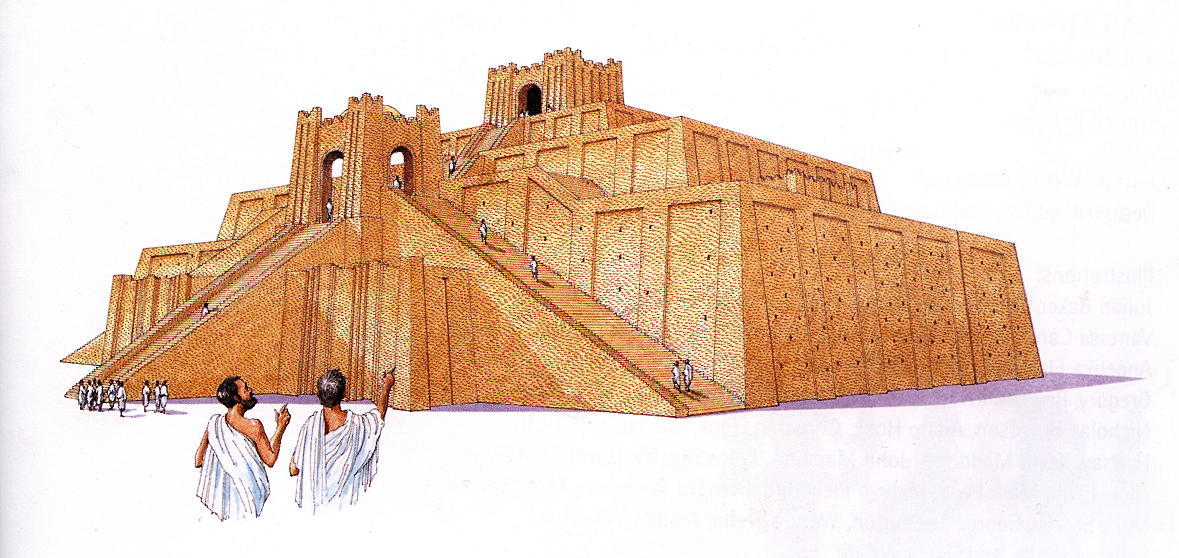

Therefore Dudu and his faithful priests went to Kuta, where in the temple of Nergal they performed a grim ritual involving human sacrifice. Nergal — the god of the destructive power of the scorching sun — displayed clear traits of a god of death and war. He unleashed unjust wars and sent dangerous diseases, including fever and plague. The phrase “the hand of Nergal” came to refer to plague and other infectious diseases. It is hardly surprising that Dudu sought the aid of this god — one of the Lords of the “Broad Abode,” the place of the dead. Thus, during the ritual there appeared the miraculous Sword of Nergal, born to slay kings. Washed in human sacrificial blood, it had a wavy flint blade and a copper hilt. Yet the underworld weapon, the Sword of Nergal, demanded blood again and again, and to appease it human sacrifices had to be offered repeatedly. Sometimes these were slaves, but more often the Sword’s own masters fed it with their blood.

Having received the Sword, Dudu went to Girsu (the capital of Lagash) and the throne passed to Enmetena’s younger son — Enannatum II. This ruler was neither robust nor strong-willed, and after five years of feeble rule (Dudu was the real ruler during this time) he passed into the Broad Abode without leaving an heir. Dudu remained the de facto ruler, but being more a priest than a king, he handed over governance to his pupil and adopted son Enentarzi.

But, strangely, upon coming to power Dudu’s favored pupil continued the policy of his predecessors. Taking the throne with Dudu’s support, Enentarzi merged the ruler’s lands with the temple lands of Ningirsu, his consort the goddess Baba and their children — the gods Igalim and Shulshagan — and with the lands of the goddess Ngatumdu. Thus, in the possession of the ruler and his family there came to be more than half of Lagash’s land. Many priests were displaced, and the administration of temple lands fell into the hands of the ruler’s servants, dependent on him. Enentarzi’s men began to exact various exactions from minor priests and from those dependent on the temples. At the same time the plight of the commoners worsened; there are vague reports that they fell into debt to the nobility, with documents recording parents selling their children due to impoverishment. All this provoked dissatisfaction across many strata of the population, and Dudu found himself between two fires — on the one hand he loved and supported Enentarzi, but on the other he was the High Priest (Sang) and could not tolerate arbitrariness in the temples.

At the same time Enentarzi knew of the Sword of Nergal, kept by Dudu, and so during the conflict between the En and the Sang, Enentarzi transferred power to his son Lugaland. Dudu hoped that at least this boy would carry out the priests’ will and that life would return to its accustomed theocratic channel. Again he was mistaken. Lugaland married Barnamtarra, the daughter of a great landowner who possessed vast estates and a forceful, energetic character. Lugaland quickly fell under her control and did her bidding alone. In fact it was Barnamtarra who ruled Lagash: she concluded treaties and trade contracts, and she, of course, had little love for the priests. Dudu’s repeated appeals to Lugaland to stop the exactions imposed by Barnamtarra were in vain. The ensi was too much under his wife’s sway to change anything. Popular discontent thus combined with the priests’ displeasure, and the accumulated resentment burst into revolt.

During the uprising Dudu, with the help of the Sword of Nergal, killed Lugaland. Yet Enentarzi, Lugaland’s father, could not forgive his adoptive father the slaying of his son. He came to the temple, seized the Sword of Nergal and with it the 63-year-old Dudu left this world. The Sang, accustomed to stepping over corpses, did not even resist; he could not raise his hands against his pupil, blinded by rage and thirst for vengeance. Barnamtarra, however, as if nothing had happened, left Lagash and returned to her estate, where she lived out a few more tranquil years. Her funeral was marked by royal pomp — the people still feared their deposed queen.

Sitting beside the dead father and son, Enentarzi did not notice the looters marauding in the palace. Overcome with grief and virtually paralyzed by his calamity, he fell by the pick of a mad peasant, who raged and smashed everything in his path.

The Sword of Nergal drank another portion of sacrificial blood.

When the rioters had calmed somewhat, the priests and the remnants of the army restored order, and by popular assembly a new ensi was chosen, since the entire ruling elite was dead.

The ruler became Urukagina, husband of Enentarzi’s sister, the only member of the royal line who received support not only from the aristocracy but also from the priests and even the poor. He accepted the kingdom, but also the curse of the Sword of Nergal. In the year after his election, around 2318 B.C., Urukagina assumed the priestly office with the title Lugal and began a new regnal count. With such authority he carried out a reform which, formally, meant that the lands of the deities Ningirsu, Baba and others were once again removed from the ruler’s ownership; the exactions contrary to custom and some other arbitrary actions of the ruler’s agents were abolished; the position of the lower priesthood and the more independent portions of those dependent on temple estates was improved; debt transactions were annulled; and ritual payments were reduced and regularized. However, the removal of temple estates from the ruler’s property was purely nominal; the entire government administration remained in place.

By this time rumors of the Sword of Nergal had spread throughout Mesopotamia. In Umma, Lagash’s long-standing enemy, Lugalzaggesi — son of the purification priest — came to power, understanding from where Lagash’s victories sprang. In the third year of Urukagina’s rule (c. 2316 B.C.) Umma and Uruk united under Lugalzaggesi’s authority, immediately increasing Umma’s strength and altering Lagash’s fortunes for the worse. In the fourth year of Urukagina’s reign (c. 2315 B.C.) Lugalzaggesi invaded Lagash and besieged its capital, the city of Girsu. Epidemics broke out in the city; Lagash’s defeat seemed imminent. But the Sword of Nergal helped Urukagina win battle and drive off the enemies.

But Lugalzaggesi did not relent. During the fifth and sixth “lugal” years of Urukagina’s reign (c. 2314–2313 B.C.) war raged over Lagashese territory and the Ummans and Urukites approached the walls of Girsu. By the sixth year (c. 2312 B.C.) all the communities and temples lying between the canal forming the border with Umma and the suburbs of Lagash and Girsu had been destroyed and ravaged. In the seventh year of Urukagina’s reign (c. 2311 B.C.) there was treachery in his camp and the eastern portion of his territory (the district of E-Ninmar) seceded from Lagash. Lugalzaggesi took advantage of this and inflicted a crushing defeat on Urukagina, seizing a good half of Lagash’s territory. The remainder of Lagash fell into desolation. However, Lugalzaggesi, understanding the stature of the Lugal, allowed Urukagina free retreat from the fortress of Girsu; yet during the preparations for withdrawal Urukagina was treacherously slain by one of his generals, who stole the Sword of Nergal and delivered it to Lugalzaggesi. In Lagash Lugalzaggesi annulled all of Urukagina’s reforms and made the city of E-Ninmar the capital of Lagash. And the bloody history of the Sword of Nergal did not end there. Its power drew rulers to it who hoped by means of the Sword to rule the world.

Sargonic ruler Sharukkin (Sargon) of Akkad was no exception. “The Legend of Sargon” records that his homeland was Azupiranu (“Saffron-town” or “Town of Crocuses”) on the Euphrates. According to the legend, Sargon rose from the common people; it was said he was the adopted son of a water-carrier and had served as gardener and cup-bearer at the Kish king Ur-Zababa’s court. Sargon’s humble origins later became a commonplace of cuneiform historical compositions. And it was precisely this background that drove him to seek the Sword of Nergal — the Sword of Kings. The beginning of Sargon’s reign is dated to the second year of Urukagina’s reign as lugal and to the twentieth year of Lugalzaggesi’s rule (c. 2316 B.C.). Choosing a capital for his state, Sargon decided not to live in any of the traditional centers but selected a city without traditions, nearly unknown, in the nome of Sippar. The city bore the name Akkade. From it the region Ki-Uri henceforth came to be called Akkad. In the third year of his reign (c. 2313 B.C.) Sargon mounted a campaign to the west, into Syria. The ruler of Ebla acknowledged Sargon’s authority and opened for him the road to the Mediterranean. In the fifth year (c. 2311 B.C.) Sargon began military operations against Lugalzaggesi and quickly routed his army and the forces of his subject ensi. Lugalzaggesi was executed, and the walls of Uruk were torn down. The Sword of Nergal fell into Sharukkin’s hands. Sargon proclaimed Inanna his patroness and attributed his victories to her aid. He gave his daughter, bearing the Sumerian name En-hedu-Ana (literally “High Priestess of the Abundance of Heaven”), to be a priestess — en (in Akkadian entu) — of the moon-god Nanna in Ur; from then on it became tradition that the eldest daughter of the king serve as entu of Nanna.

After fifty-five years of continuous wars, Sargon died.

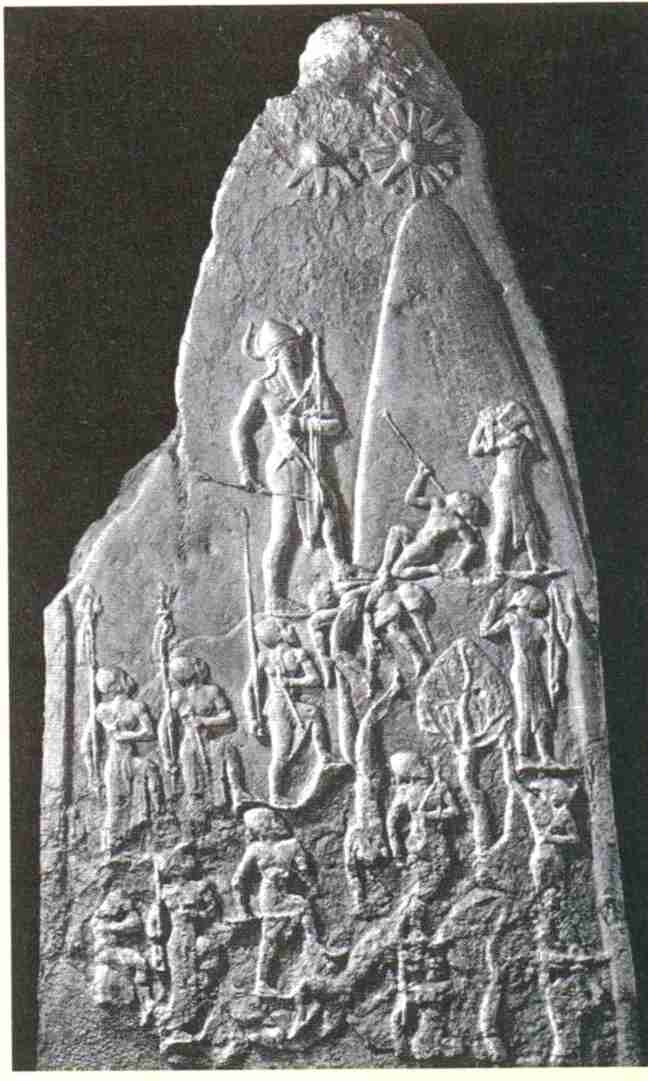

None of his successors who took up the Sword of Nergal died a natural death. His son Rimush was killed in the tenth year of his rule by nobles who pelted him with heavy stone seals. Rimush’s younger brother, Manishtushu, also perished as the result of a noble conspiracy. Manishtushu’s son, Naram-Sin, began his reign facing rebellion. The citizens of Kish elected a certain Iphur-Kish as king. Many cities in various parts of the vast realm joined their uprising. Records speak of Naram-Sin’s victories over the armies of these nine kings within one year and of the capture of three kings, leaders of those armies. He ordered the captives to be burned before the god Enlil in Nippur.

Although Naram-Sin secured Akkad’s greatest prosperity, at the end of his reign he fell into conflict with the priesthood because Naram-Sin allowed his troops to burst into E-kur, Enlil’s temple in Nippur. With copper axes they smashed the temple, seized Nippur’s treasures and carried them off to Akkad. For such desecration the gods were enraged with Naram-Sin and sent a curse upon Akkad, and Enlil, to protect the city of Nippur, called the Gutians down from the hills. The Gutians, led by their chieftain Enrida-vasir, invaded Sumer, captured Nippur and put an end to Naram-Sin’s detachments’ encroachments on Enlil’s temple. Naram-Sin barely repelled the Gutian onslaught. Yet invasions by eastern and north-eastern tribes into the two-river land continued. Hostile actions by the Gutians and other mountain peoples against Naram-Sin led to the formation of a new coalition hostile to Akkad. It included the city of Nippur itself, Simurrum (against which even Sargon had campaigned), and several other cities of Mesopotamia. Thus, after thirty-seven years of rule, Naram-Sin fell in battle with the Gutians. His successor and grandson, Shar-Kali-sharri, tried to repel Gutian attacks, but was also killed.

In the tidal waves of the Gutians, traces of the Sword of Nergal are lost, passing wholly into the realm of myth. Perhaps other great conquerors wielded it, or perhaps it returned to the same place from which it had appeared — the “Broad Abode.”

Thank you

A wonderful historical essay!

Thank you!