Schools and Teachings of Nonduality

The contemporary spiritual milieu very often uses the word “nonduality” to give a lofty veneer to their mind’s laziness, ignoring contradictions and selectively perceiving only part of reality. In this context, for a serious Wayfarer the very word «advaita» becomes synonymous with trivialization and hypocrisy. At the same time, both the schools of nondual perspective and the overcoming of duality remain among the most important approaches for harmonizing and liberating the mind.

At the same time, awareness of nonduality — is a fundamental stage on any path of spiritual and intellectual development, and therefore it is addressed in many philosophical and religious traditions. Nonduality as a concept asserts that the apparent distinctions between subject and object, “I” and “not-I”, matter and mind, deity and cosmos are the result of error of perception, whereas the underlying “true reality” is indivisible and whole. Discovering and experiencing this unity transforms the mind, dismantles limiting concepts, and opens access to a genuine understanding of the essence, foundations, and purpose of existence.

From this standpoint it becomes clear that dualistic perception is often the source of suffering: by separating “I” and “others”, the mind falls into the trap of attachment, anger, fear, and desire, and awareness of nonduality helps free the mind from these limitations.

Different philosophical and religious schools offer a variety of approaches to the methodology of understanding and experiencing nonduality and to describing and interpreting it. These paths are designed for different types of people, different modes of thought and perception, helping each seeker find a suitable method that suits them best for understanding themselves and the world. At the same time, each tradition interprets nonduality in its own way, adapting it to its philosophical, religious, and practical context.

It is widely known that in the East especially significant are the approaches and views of the six schools that postulate nonduality as their central concept:

1. Advaita Vedanta.

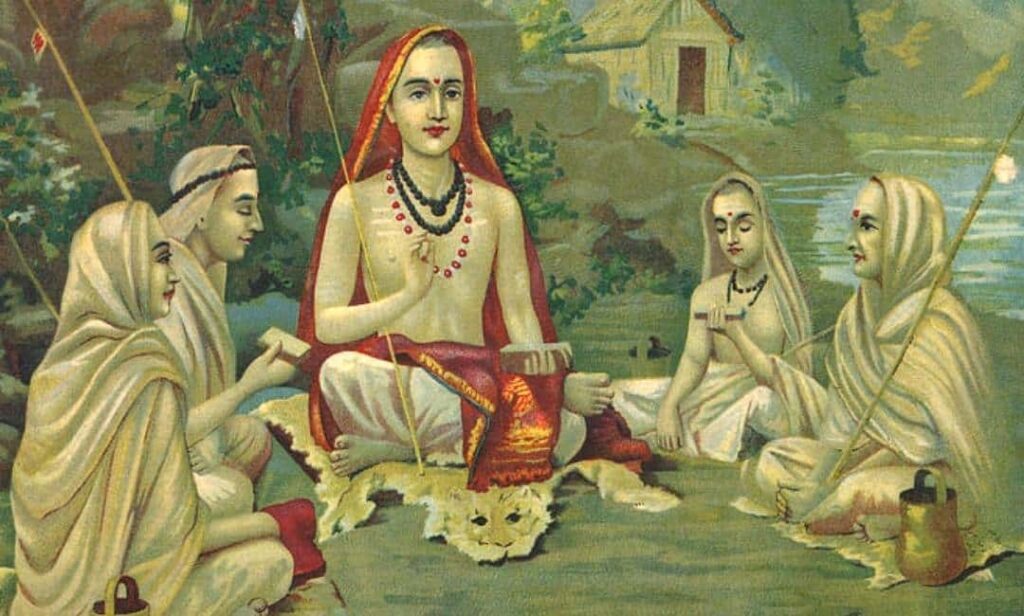

The most famous philosopher and systematizer of this system is Shankara (Shankaracharya, ca. 788–820 CE). He articulated the ideas of nonduality (advaita) as “true” reality in their most familiar form. In particular, he asserted that only the Absolute, Brahman, is real, while the world is an illusion (maya). At the same time, Shankara regarded maya as a property of Brahman, and therefore, from his point of view, a “world without illusion” is impossible. His commentaries on the Upanishads, the Bhagavad Gita, and the Brahma-sutras became the foundation of this tradition. Shankara reinterpreted and adapted the ancient Vedic texts and the philosophy of the Upanishads in order to develop his distinctly monistic system of nonduality.

2. Vishishtadvaita.

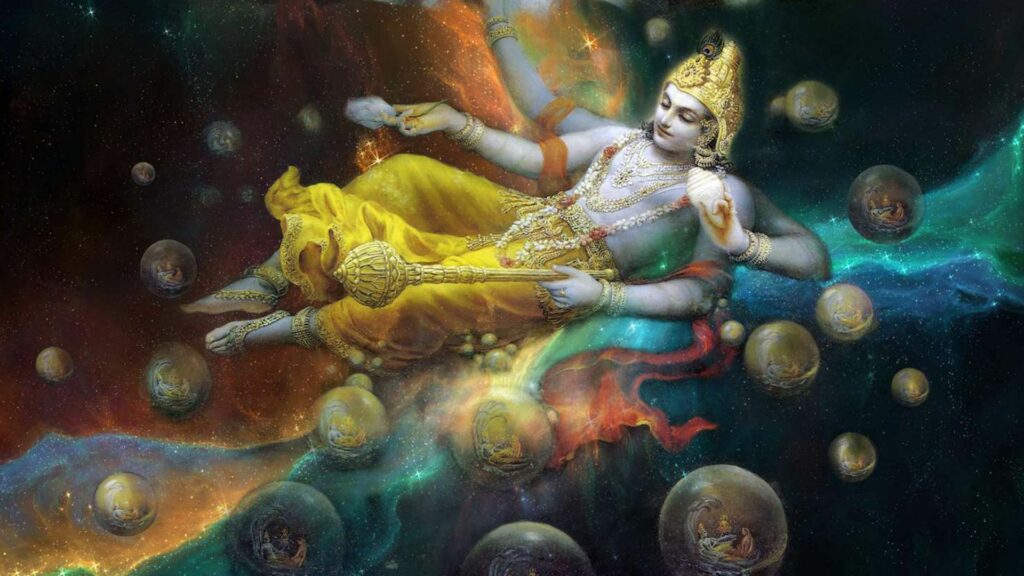

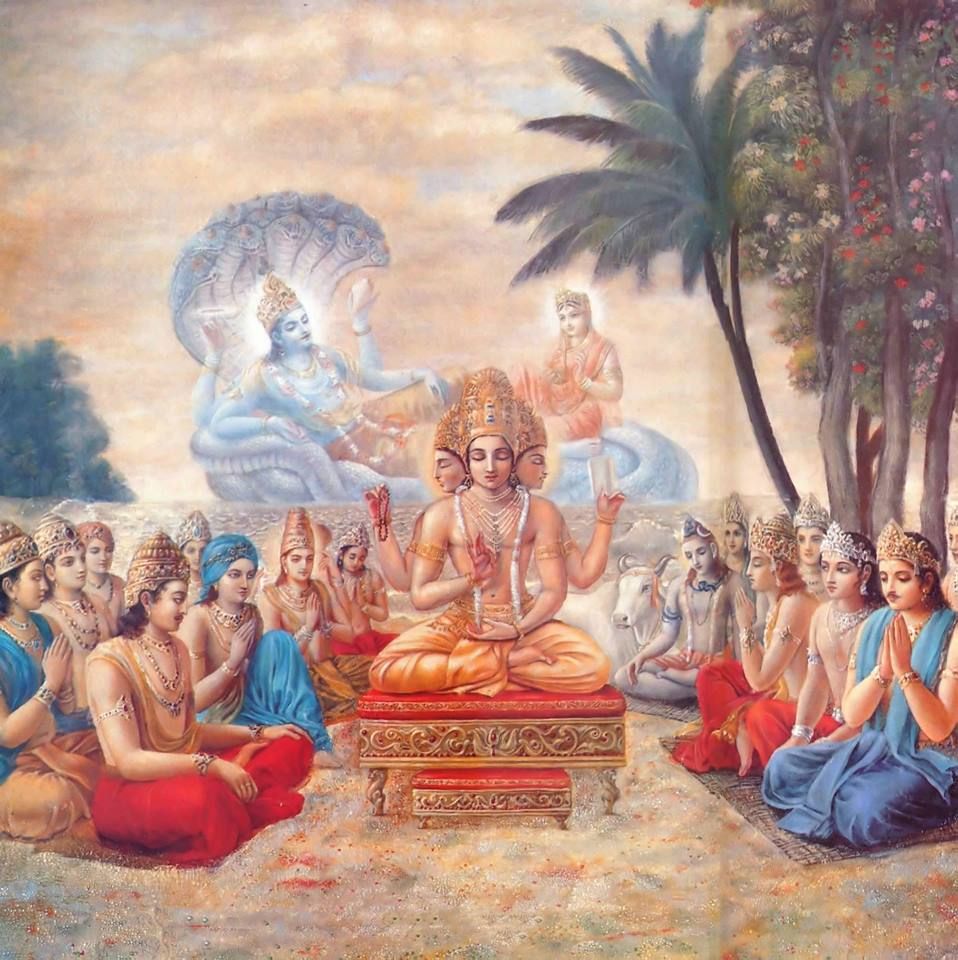

The second important school of advaita was less categorical in its monism. This school combines elements of nonduality with theism. Vishishtadvaita, or the school of qualified nonduality, was founded by Ramanuja (ca. 1017–1137 CE), who argued that although true reality belongs only to the One (Brahman), He is not absolutely transcendent but possesses knowable or manifest qualities (saguna). At the same time, the world and souls are also in a certain sense real, yet they depend on Brahman as parts of his being. This philosophy is based on commentaries on the Brahma-sutras and the Vishnu-sahasranama.

3. Kashmir Shaivism.

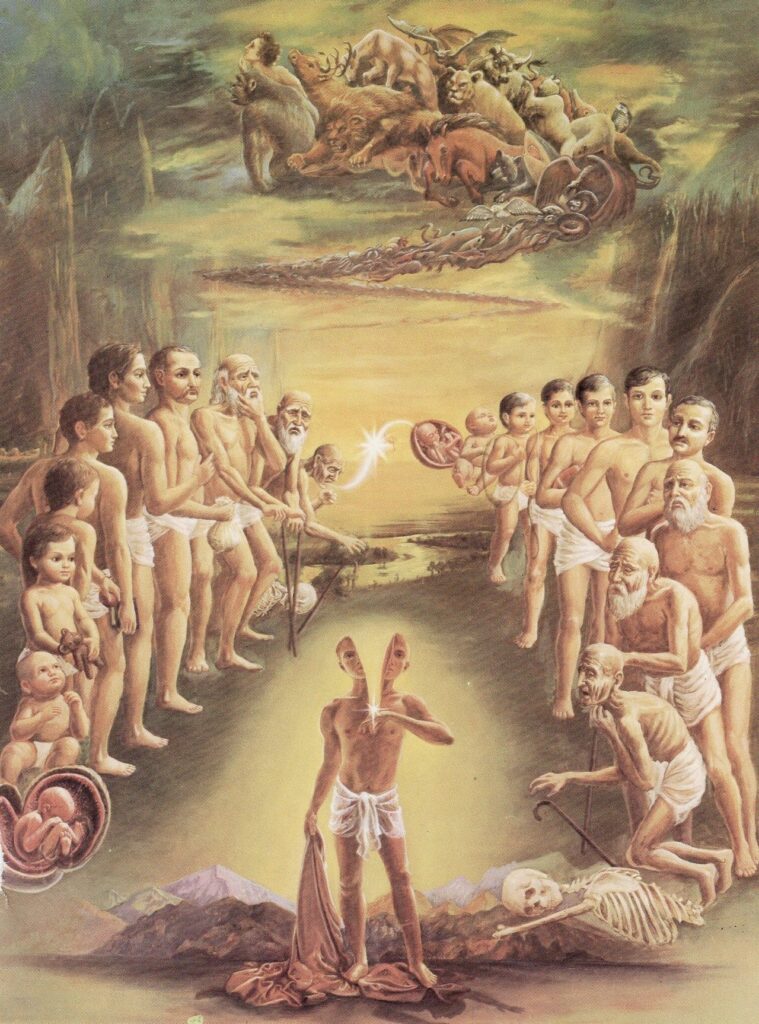

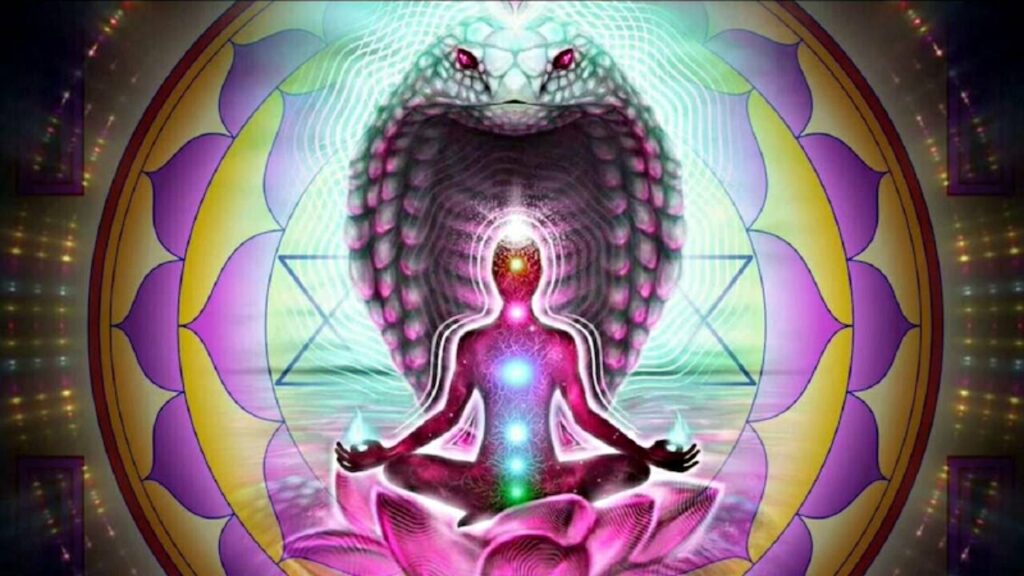

The third school founded on advaitic concepts is the so-called Kashmir Shaivism. Its founder is generally considered to be Vasugupta (fl. ca. 9th century CE), to whom the discovery of the primary text of this tradition — the Shiva Sutras — is attributed. The philosophy of this school centers on the nonduality of the mind (of Shiva) and its self-manifestation through energy (Shakti). Thus reality in this school is perceived as the manifestation of universal mind — Shiva. The world in this tradition is not illusory but an expression of energy (Shakti) inseparable from the Absolute. The concept of spanda as the pulsation of mind reflects the nonduality of the static and the dynamic.

Another influential systematizer of Kashmir Shaivism was Abhinavagupta (ca. 950–1020 CE). His works, notably the Tantraloka, united the philosophical, tantric, and yogic aspects of Shaivism and had a profound influence on Hinduism as a religion and on Indian culture in general.

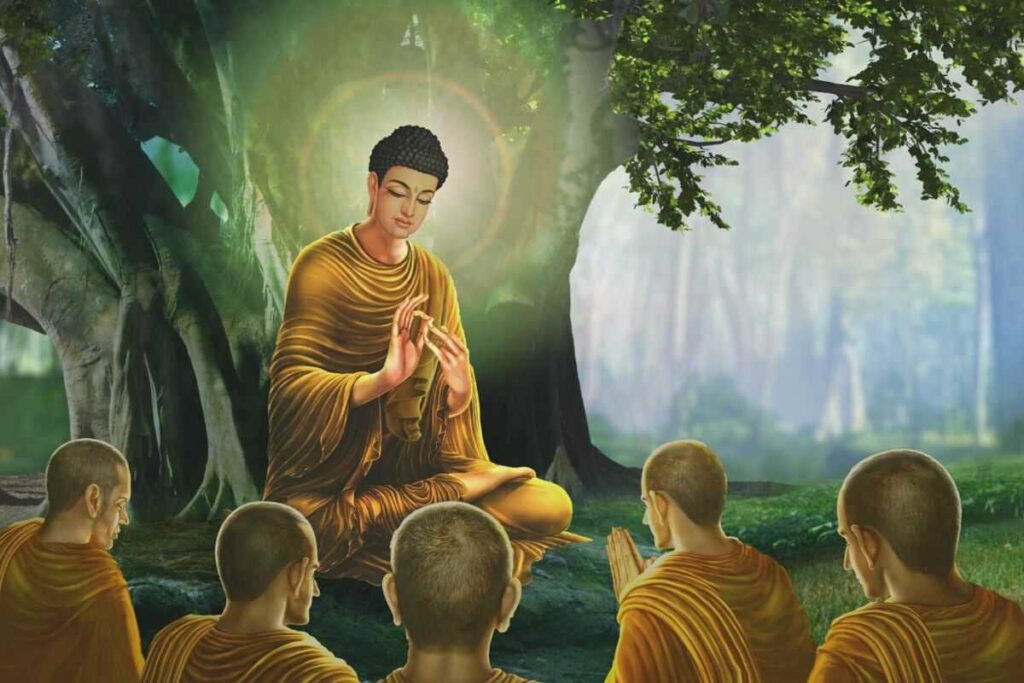

4. Mahayana Buddhism.

At the same time, all the new schools of Hindu thought (Vedanta, Samkhya/Yoga, Nyaya/Vaisheshika, Mimamsa) took shape under the influence of Buddhism — either borrowing from it or in polemic with it.

Nagarjuna (ca. 150–250 CE), the founder of the Madhyamaka school (“The Middle Way“), played a central role in shaping Buddhism as a rigorous philosophical tradition. His concept of shunyata (emptiness) systematized the teaching of dependent origination (pratītya-samutpāda), asserting that all phenomena lack intrinsic essence and became a central concept in Mahayana. He also applied strict logical analysis to demonstrate the impossibility of stable existence either as entities or as non-existence, asserting the nonduality of reality.

Advaita in Mahayana doctrine manifests in the denial of a difference between samsara and nirvana when their true nature — emptiness (shunyata) — is realized. In other words, samsara and nirvana are nondual because both are aspects of emptiness. Any division, including subject and object, is a delusion of the mind.

A significant contribution to Mahayana philosophy was also made by the founders of the Yogachara school (“Practice of Yoga“) — Asanga and Vasubandhu (ca. 4th–5th centuries CE). Asanga focused on the development of practices and a philosophy of mind, while Vasubandhu in works such as the Vijñaptimātratā-siddhi systematized the philosophy of mind-only (cittamatra).

5. Vajrayana

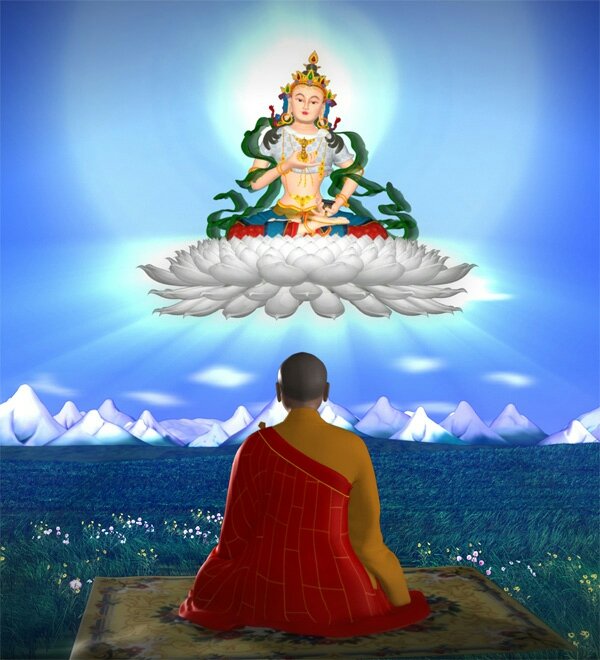

Although Vajrayana is closely connected with Mahayana, its methods and philosophy formed later with the development of tantric Buddhism, which integrated elements of practical work with energy, the body, and visualization. Vajrayana regards the world as primordially pure, where the nonduality of emptiness and form is experienced through tantric practices that reveal the inseparability of “ordinary” and “absolute” mind.

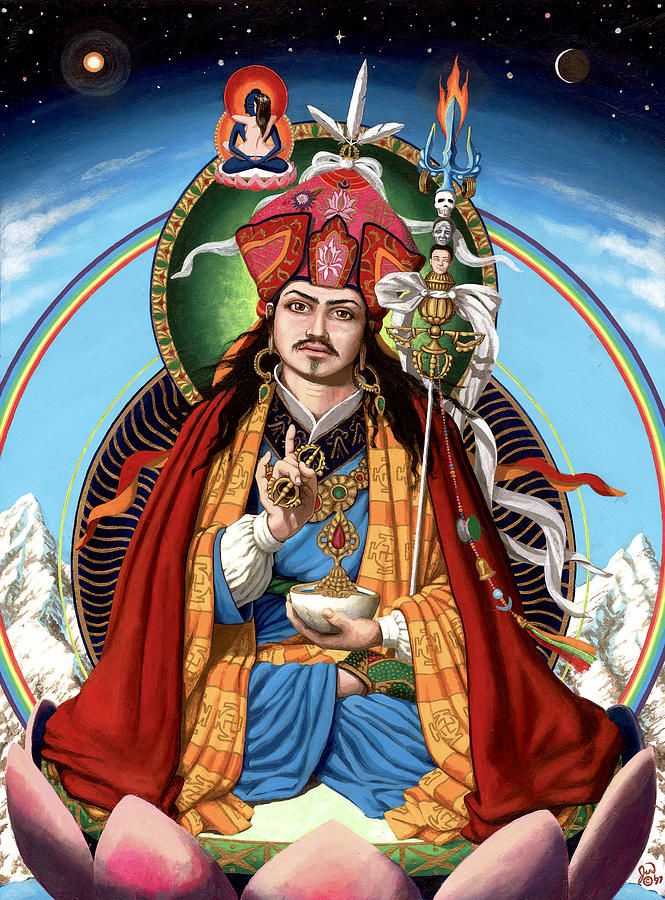

The founder of tantric Buddhism in Tibet — Guru Padmasambhava (fl. ca. 8th century CE) — merged Mahayana philosophy with tantric practices. He is regarded as a manifestation of the Buddha Amitabha and an embodiment of Vajrasattva, and is the founder of the Tibetan Nyingma school.

In this school nonduality is not merely recognized but directly experienced through an integration of meditation and daily life, where the world is perceived as an expression of buddha-nature (tathāgatagarbha).

Nagarjuna’s works are also important for Vajrayana philosophy, especially in its emphases on emptiness and tantric methods.

6. The Naths

The Nath tradition combines elements of nonduality and tantra, but its formation as a philosophical school occurred later than Mahayana and Advaita Vedanta. Like Advaita Vedanta or Kashmir Shaivism, the Naths assert that reality is nondual. However, their emphasis is on the practical realization of this nonduality through yoga and energetic methods.

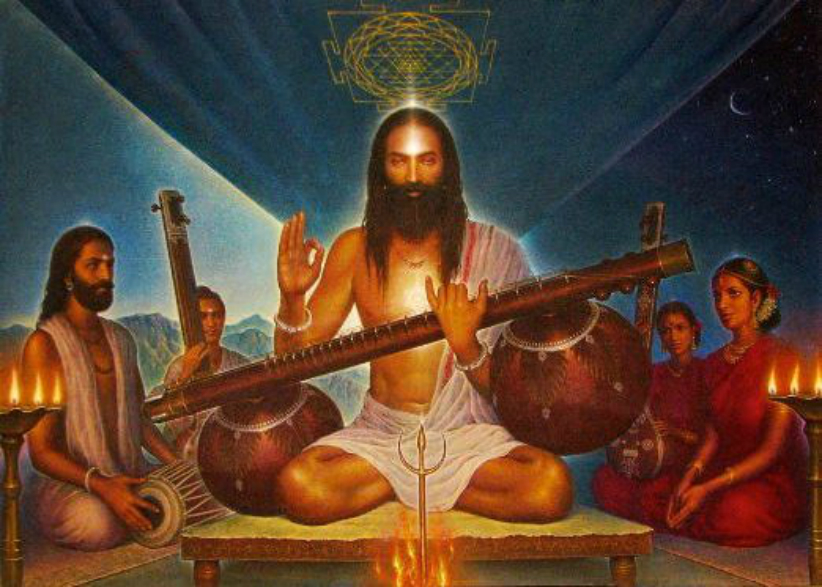

The founder of the Nath tradition is Matsyendranath (fl. ca. 9th–10th centuries CE). His teaching includes elements of hatha-yoga, tantra, and Shaivism. He is credited with tantric texts such as the Kaularnava-tantra.

The most influential teacher of the Naths, the systematizer of their philosophy and practices, is Gorakshanath (Gorakhnath, fl. ca. 10th–11th centuries CE). He is attributed with the creation of texts on hatha-yoga and with forming Nath-yoga as a tradition.

The Naths borrow from Advaita the idea of an absolute reality beyond duality, from Kashmir Shaivism the understanding of energy (Shakti) as a manifestation of that reality, and they also use practices of self-knowledge and contemplation characteristic of Buddhist meditation methods.

Let us compare the main characteristics of these schools:

Understanding of nonduality

Advaita Vedanta asserts that only Brahman is the real ground of everything, and the world is an illusion (maya). According to advaita, atman (the individual “I”) is entirely identical with Brahman, and all distinctions are the result of ignorance (avidya). Awareness of nonduality is achieved through self-inquiry and philosophical reflection.

Vishishtadvaita describes reality as nondual but with qualifications: according to this school’s views, Brahman includes the world and souls, which are his parts, much as a body is part of a person. Brahman is regarded as personal and possessing describable qualities (saguna). Awareness of nonduality is attained through bhakti (devotion), where the disciple realizes their connection with Brahman.

Kashmir Shaivism presents reality as the mind of Shiva, which manifests through its energy (Shakti). All distinctions between subject and object are seen as pulsations (spanda) of the one mind. Practitioners attain awareness of nonduality through meditation on the unity of Shiva and Shakti, and through experiencing spanda.

Mahayana (Madhyamaka) holds that all phenomena are empty (shunyata), that is, devoid of intrinsic essence. Samsara and nirvana are in their essence nondual because both are aspects of emptiness. Awareness of nonduality is achieved through meditation on emptiness and logical refutation of dualistic concepts.

Vajrayana regards reality as primordially pure and nondual, where emptiness and form constitute a unity. All phenomena are perceived as manifestations of the energy of nondual mind. Awareness of nonduality is attained through tantric practices such as deity visualization, working with energy, and integrating meditation into everyday life.

The Naths perceive nonduality as the unity of energy (Shakti) and mind (Shiva). This unity is experienced through the transformation of body, mind, and energy. Practitioners achieve awareness of nonduality via hatha-yoga, pranayama, and the awakening of kundalini.

As we have already seen, their views also differ on the nature of the Absolute and Reality:

Advaita Vedanta describes the Absolute as Brahman, which is the only reality and is absolutely nondual. Brahman has no qualities (nirguna) and lies beyond description. The world is perceived as an illusion (maya) arising from ignorance (avidya). The reality of the world is conditional and disappears upon the realization of the true nature of Brahman.

Vishishtadvaita asserts that although Brahman is the highest reality, he possesses qualities (saguna) and includes the world and souls as his parts. The world is considered real and dependent on Brahman, being an integral aspect of his essence. The Absolute here is generally perceived as a personal God, accessible through devotion and bhakti.

Kashmir Shaivism regards the Absolute as Shiva — universal mind that includes everything. Shiva manifests through Shakti, his dynamic, creative energy, which generates the world and its phenomena. The reality of the world is actual, yet it is perceived as a manifestation of the one mind. Shiva and Shakti are indivisible, and their interaction expresses the pulsation of mind (spanda).

Mahayana (Madhyamaka) interprets the Absolute as emptiness (shunyata), which lacks inherent essence and constitutes the basis of all phenomena. The reality of the world is seen as dependent origination (pratītya-samutpāda), where no phenomenon exists independently. Samsara and nirvana are nondual because both are aspects of emptiness.

Vajrayana describes the Absolute as primordially pure reality, where emptiness and form are nondual. The Absolute manifests as light and energy, and reality is perceived as an expression of buddha-nature. The world is not separated from the Absolute and is regarded as a field for practice, in which every form can be transformed into an enlightened state.

The Naths see the Absolute as the unity of Shiva (mind) and Shakti (energy). The Absolute is expressed through the interaction of static mind and dynamic energy, and this process manifests reality. The world is perceived as real because it is an expression of the Absolute, and awareness of this reality is achieved through the transformation of body and mind.

However, although the six traditions considered here understand the nature of the Absolute and reality differently, their common goal is to help their adherent overcome illusions, to realize (and sometimes directly experience) the unity underlying all phenomena.

Nature of the Soul is also described differently:

An important aspect distinguishing the views of the schools under consideration is their representation of reality and the nature of individual mind (atman).

Thus, Advaita Vedanta asserts that the soul (atman) is absolutely identical with Brahman. From this standpoint, the individuality of the soul is an illusion born of ignorance (avidya). Upon achieving liberation (moksha) the soul merges with the Absolute, losing all individuality, since its nondual nature is realized.

By contrast, Vishishtadvaita regards the soul (jiva) as real and retaining individuality even after liberation. In the state of moksha the soul remains distinct from Brahman, yet in full union with him as part of his “body”, enjoying infinite bliss in his presence.

Kashmir Shaivism holds that the soul is a manifestation of the universal mind of Shiva, and its individuality is a temporary function of the play of Shiva and Shakti. Upon realizing its true nature the soul understands its unity with Shiva, although its individuality may remain as an aspect of the Absolute’s manifestation.

Mahayana (Madhyamaka) rejects the existence of a permanent individual soul (anatman). From its position, individuality is merely a set of interdependent processes, a stream of elementary cognitive events (dharmas) that cease upon the attainment of enlightenment. After liberation not only does attachment to the “I” disappear, but the very concept of individuality dissolves.

Vajrayana agrees with Mahayana that the soul has no permanent essence and that individuality is an illusion. However, through tantric practices the mind is transformed so as to merge with the absolute reality, where the personal structure dissolves into primordial purity.

The teaching of the Naths asserts that the soul is a union of mind (Shiva) and energy (Shakti). The soul’s individuality is an expression of the Absolute, and whether it is preserved or dissolved depends on the level of awareness. An awakened soul may retain individuality as a means of manifesting divine will or may fully merge with the Absolute.

Methods of spiritual practice

Because the doctrines of each school have their own specifics, the methods used on their basis are also characterized by different emphases.

In particular, Advaita Vedanta places primary emphasis on intellectual practice (jnana-yoga), where working with the body is not a priority. The main attention is given to philosophical reflection, self-inquiry, and meditation, which makes physical aspects nonessential for spiritual progress.

Vishishtadvaita likewise does not attach special importance to work with the body. The emphasis is on emotional and spiritual aspects through bhakti (devotion), prayers, rituals, and the chanting of God’s names. Work with the body is limited to general practices of Hindu ritual.

In other words, Advaita Vedanta and Vishishtadvaita minimize the role of the body, focusing on intellectual or emotional practice.

Kashmir Shaivism includes work with the body through tantric practices aimed at awakening Shakti. Although the emphasis remains on mind and its pulsation (spanda), working with energy through asanas, pranayama, and concentration on chakras is an important part of this Way.

Vajrayana actively uses the body as an instrument of transformation. Through tantric rituals, visualization, mantras, mudras, and pranayama the body becomes a field for working with energy, helping to integrate meditation and physical existence into a single process of transforming obscurations into wisdom.

Thus, Kashmir Shaivism and Vajrayana regard the body as part of spiritual work, especially through interaction with energy and tantric methods.

The Naths put strong emphasis on working with the body. Through hatha-yoga, pranayama, the awakening of kundalini, and cleansing practices (shatkarmas) the body is regarded as an important instrument for attaining spiritual experience. The union of energy (Shakti) and mind (Shiva) within the body is a key stage on the spiritual Way.

Mahayana (Madhyamaka) is primarily focused on meditation and intellectual practice, where work with the body does not hold a central place. Physical practices may be used only as auxiliaries, while the main emphasis is on awareness of emptiness and the interdependence of all phenomena.

Liberation (moksha)

The ultimate goal of development — liberation (moksha or nirvana) — is also viewed somewhat differently.

Advaita Vedanta regards liberation (moksha) as the full realization of nonduality, where the individual “I” (atman) and the Absolute (Brahman) are recognized as identical. Liberation means the destruction of illusion (maya) and merging with Brahman, which leads to the disappearance of individuality and abiding in eternal mind and bliss.

Vishishtadvaita understands liberation as achieving eternal dwelling in union with Brahman, but without the loss of the soul’s individuality (jiva). In the state of moksha the soul remains personal while abiding in harmony with Brahman, enjoying his infinite bliss and grace.

Kashmir Shaivism describes liberation as the realization that the individual soul has always been and remains one with the universal mind of Shiva. Liberation is the restoration of the inner sense of one’s true nature through experiencing the unity of Shiva and Shakti, without the need to deny the world.

Mahayana (Madhyamaka) defines liberation as the realization of the emptiness (shunyata) of all phenomena, which leads to the breaking of attachment to the illusion of “I” and all dualistic concepts. Liberation does not mean the annihilation of individual mind, but its transformation into a state free from suffering and delusion.

Vajrayana understands liberation as the realization of primordial purity and nonduality of mind, where emptiness and form are one. Through tantric practices the practitioner attains the state of buddhahood, in which they simultaneously abide in the light of emptiness and the active form of enlightened activity.

The Naths view liberation as attaining a state of complete unity of Shiva and Shakti within body and mind. This includes liberation from karmic attachments as well as physical transformation through the awakening of kundalini. Liberation is perceived as an inner awareness of one’s nondual nature.

Comparison with other traditions

Thus, each of the schools has both its own worldview and practical specifics, which ultimately determine which Way and which tradition will suit a particular Wayfarer and seeker. Let us try once again to summarize some important aspects.

1. The initial idea – the fundamental basis that constitutes the “core” of the system.

For Advaita Vedanta this fundamental point is the notion of an absolutely nondual reality; only Brahman is real, while the world and individuality are an illusion (maya) arising from ignorance (avidya).

For Vishishtadvaita reality is nondual but has “qualifications”: the world and souls are real parts of Brahman, much as a body is part of a person.

According to Kashmir Shaivism, everything is a manifestation of Shiva’s mind; the world is a real expression of the interaction of Shiva and Shakti, and their pulsation (spanda) underlies all phenomena.

In Mahayana all phenomena lack intrinsic essence (shunyata) and exist due to interdependence (pratītya-samutpāda).

For Vajrayana reality is primordially pure and nondual; emptiness and form are one, and all phenomena are expressions of buddha-nature.

In the tradition of the Naths reality is the unity of mind (Shiva) and energy (Shakti), manifesting through body and mind.

Different traditions relate to the body in very different ways:

In Advaita Vedanta work with the body receives minimal attention; spiritual progress is achieved through philosophical reflection and self-inquiry.

In Vishishtadvaita work with the body likewise does not play an important role; the emphasis is on devotion and ritual.

In Kashmir Shaivism the body is widely used as an instrument in tantric practices for realizing nonduality.

For Mahayana the body has minimal significance; its main focus is intellectual and meditative work.

At the same time, Vajrayana actively employs the body through mantras, mudras, visualizations, and energy work.

In the tradition of the Naths the body plays a central role and is regarded as a tool for spiritual transformation through hatha-yoga and pranayama.

The schools differ not only in their attitude to overt manifestations — the body and attributes — but also to the very energy that underlies manifested existence

In the system of Advaita Vedanta there is no particular work with energy; the emphasis is primarily on intellectual understanding and self-inquiry.

In Vishishtadvaita work with energy is also minimal; the system places its main emphasis on rituals and prayers.

For Kashmir Shaivism work with energy is a key part of practice, using interaction with Shakti to realize unity with Shiva.

In Mahayana specific work with energy is practically absent, since the focus is on meditation and realization of emptiness.

By contrast, in Vajrayana energy plays a central role; its practices aim at transformation primarily through work with energetic currents.

For the Naths work with energy is also foundational, especially through the awakening of kundalini.

Accordingly, the goal of liberation is formulated differently:

In Advaita Vedanta it is the complete dissolution of individuality in Brahman, the realization of nonduality and the destruction of the illusion of maya.

In Vishishtadvaita it is union with Brahman without the loss of individuality, abiding in his infinite bliss.

For Kashmir Shaivism the goal is the experience that the individual soul has always been one with Shiva; the world and individuality are accepted as part of the Absolute.

In Mahayana the aim is the realization of the emptiness of all phenomena, leading to the overcoming of suffering and the dissolution of attachments to the illusion of “I”.

In Vajrayana this appears as the realization of primal purity of mind and the nonduality of emptiness and form, achieved through transformation.

For the tradition of the Naths the task is the union of mind and energy in body and mind, and the realization of nonduality through inner transformation.

It is clear that the methods and tools by which adherents of these schools strive to go beyond duality also differ:

In Advaita Vedanta these are primarily jnana-yoga (the Way of knowledge), as well as the aforementioned self-inquiry and the study of philosophical texts.

For Vishishtadvaita the instrument is bhakti-yoga (the Way of devotion), as well as mantra-yana, prayers, rituals, and chanting the names of God.

In Kashmir Shaivism the practices are primarily meditations on Shiva and his spanda, as well as tantric rituals, work with chakras, and their energies.

The main method of Mahayana is the development of the Enlightened Aspiration (bodhicitta), meditation on emptiness, analysis of interdependence, philosophical debate, and logical refutation of concepts.

Vajrayana uses deity-yoga methods: visualizations, mantras and mandalas, as well as tantric rituals, pranayama techniques, certain postures and visualizations of energy currents, drops and “winds”, and mudras.

Among the methods of the Naths are hatha-yoga, pranayama, kundalini-yoga, and cleansing practices (shatkarmas).

Thus, the traditions considered develop the concept of nonduality from different perspectives: some emphasize reason (Advaita Vedanta, Mahayana), others the emotional connection with the Absolute (Vishishtadvaita). Kashmir Shaivism, Vajrayana, and the Naths integrate work with body, energy, and mind, creating practices that emphasize experiencing nonduality within existence itself. This approach gives each tradition its distinctive features, although they are united by the common goal — the awareness of the unity of all that exists.

Two Hindu approaches to advaita, growing out of Vaishnavism and Shaivism, bear the imprint of those traditions: Shaivism emphasizes above all the transcendental and universal aspect of God, which favors nondual interpretations and mystical practices, while Vaishnavism is more oriented toward the subjective aspect of God, which forms the basis for dualistic views and personal relationships with the Divine.

Of the schools of nonduality discussed, Mahayana is evidently the oldest. Its philosophical foundations began to form in the 2nd–3rd centuries CE, especially with the works of the aforementioned Nagarjuna (the founder of Madhyamaka) and somewhat later with the emergence of the Yogachara school (4th–5th centuries). Mahayana proclaimed concepts of emptiness (shunyata) and the nonduality of emptiness and form, which became its basis.

At the same time, although Hinduism as a religious tradition is considerably older than Buddhism, tracing back to Vedic culture (ca. 1500–500 BCE), as a philosophical system it received significant development only in dialogue with Buddhism, which arose in the 5th–4th centuries BCE. In response to Buddhist ideas about emptiness, the absence of a self, and causality, Hinduism developed its philosophical schools, in particular — Advaita Vedanta, Samkhya, and Nyaya.

At the same time, the teachings considered describe four variants of the origin of reality: 1) as the “play” of Shakti, is, as the manifestation of the Highest mind in its energy (Kashmir Shaivism), 2) as subject-object relations (Vishishtadvaita), 3) as an endless obscuration (Buddhism), and 4) as maya that arose for reasons unknown (Advaita Vedanta). From this perspective, for Kashmir Shaivism reality is the creative self-expression of the Absolute through energy; in Vishishtadvaita it is the expression of the relations between God, the world, and souls; from the Buddhist viewpoint it is an illusion conditioned by infinite interdependence; and for Advaita Vedanta it is an illusion arising through maya, the cause of which is unknowable.

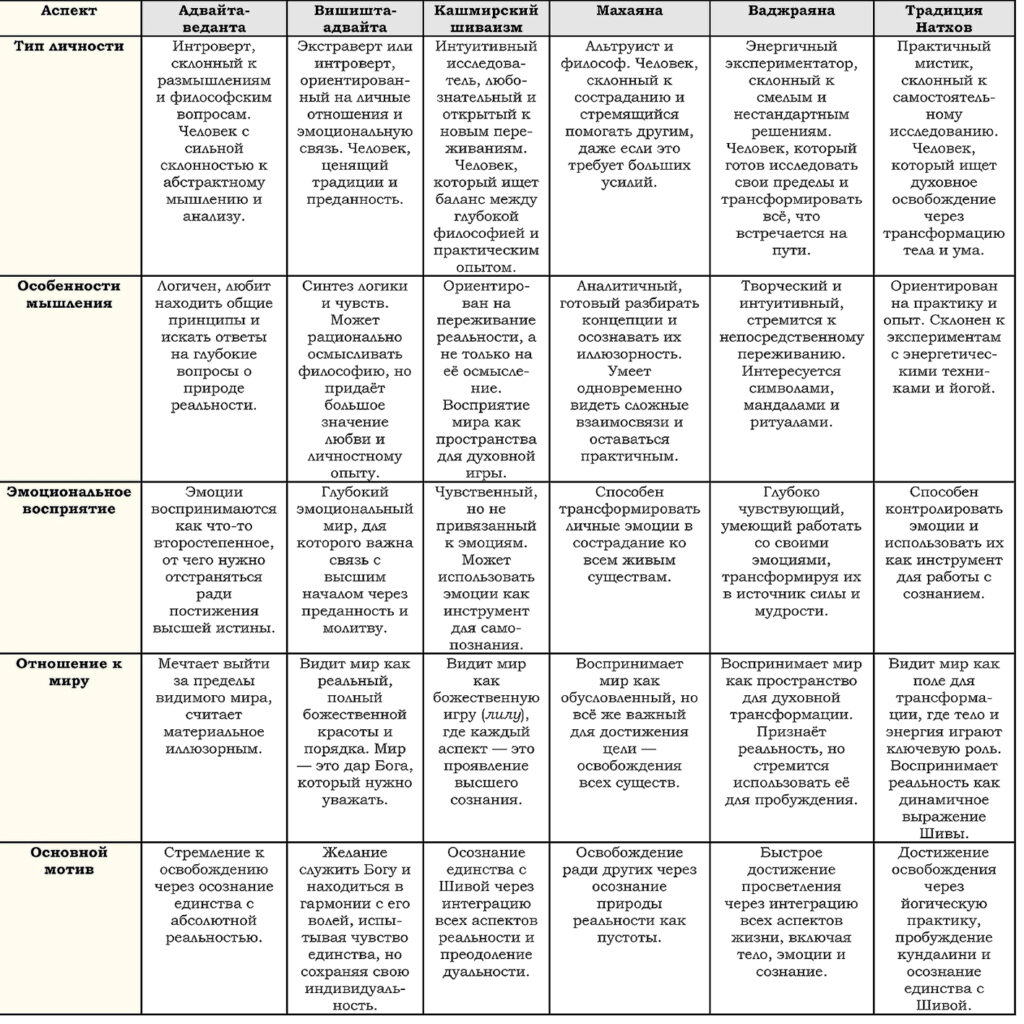

Each of the Ways differs not only in its views but also suits different Wayfarers:

Psychological profile of the schools of nonduality

Thus, one can say that:

Advaita Vedanta suits rational introverts inclined to philosophy.

Vishishtadvaita — for emotional and devoted natures seeking a personal connection with God.

Kashmir Shaivism — for intuitive explorers seeking a balance between philosophy and practice.

Mahayana — for altruists and philosophers aiming to help others.

Vajrayana — for energetic experimenters ready for rapid and intense transformations.

The Nath tradition — for practical mystics seeking self-knowledge through the transformation of body and energy.

The criteria for success on each of the described spiritual Ways are, in one way or another, connected with progress in the awareness of reality, transformation of perception and the inner state, reduction of suffering, and the integration of higher states of mind into everyday life.

In Advaita Vedanta this is the realization of the identity of atman and Brahman, the disappearance of attachments and anxieties.

In Vishishtadvaita — deep devotion to God, harmony with the world, and the joy of service.

In Kashmir Shaivism — the experience of the vibration of mind, the integration of all aspects of life into unity.

In Mahayana — the development of bodhicitta, realization of emptiness, and reduction of suffering.

In Vajrayana — the transformation of emotions, realization of the nonduality of emptiness and form, and the integration of ritual.

In The Nath tradition — the awakening of kundalini, control of body and mind, and the realization of unity with Shiva.

This is an amazing article! I am so glad that you exist, dear En.

Thank you for your endless work for everyone. Question. I get the impression that some people contain many approaches. It is difficult to differentiate. Is this so?

Of course, any classification is always quite conditional and only fair under great simplifications, however, it helps to understand the hierarchy of the engines of the psyche. In other words, although the elements of feelings, reason, and will are active in every consciousness, there are many impulses originating from the conscious and unconscious areas of the psyche, their ‘energetic effectiveness’ is different, and therefore to figure out which contribute more, have greater potential, and which are more secondary in this psychocomplex, their classification and hierarchization is needed. It’s always much easier to influence any system if you engage its more key components, rather than trying to ‘go from the tail’.

Thank you for your work and for writing interesting articles. Padmasambhava is certainly an authority. Personally, I have developed cubit thinking for myself. This means that the answers to any thought and action are not just two but four, leading to a completely new philosophy and moving away from the concepts of good and evil. That is, any action develops either relationships, wisdom, intellect, or, as you write, the energy of the weasel. The next situation and the solution from it also give four choices from some important qualities.